By Cathy Gassenheimer

Executive Vice President

Alabama Best Practices Center

Have you ever found yourself in the situation where you become aware of something and then everywhere you turn you hear or see something similar? It might go on for days or weeks!

The first time I remember this happening was in graduate school when my professor mentioned the country of Bahrain. I had never heard of it and I wanted to learn more. In the following weeks it seemed like every time I read the paper or listened to the news, Bahrain was mentioned.

Since the pandemic began, I’ve had the same “echo effect” with the concept of curiosity. Unlike my Bahrain example, all of us are familiar with the term and could probably rattle off a quick definition. In the past year, though, the idea of curiosity has been stuck in my brain – and my definition has begun to expand as I’ve searched out (or stumbled across) more information and insight. I’ve come to see that curiosity is not simply one more tool in the engagement toolkit but an innate human trait that can help all of us in a multitude of ways.

Since the pandemic began, I’ve had the same “echo effect” with the concept of curiosity. Unlike my Bahrain example, all of us are familiar with the term and could probably rattle off a quick definition. In the past year, though, the idea of curiosity has been stuck in my brain – and my definition has begun to expand as I’ve searched out (or stumbled across) more information and insight. I’ve come to see that curiosity is not simply one more tool in the engagement toolkit but an innate human trait that can help all of us in a multitude of ways.

Because I now believe curiosity to be a kind of “superpower” that we can all tap into, I’ve created a guide to some of the ways we can put it to good use. This list is certainly not exhaustive, and I hope you’ll be curious enough to help expand it!

💡As an Important Learning Tool

Let’s start with the most obvious use of curiosity: to engage others to learn more about a concept or idea. If I quoted all of the education experts touting curiosity, this blog would be the length of a novel! Instead, let me quote my friend and colleague Bryan Goodwin who has written entire books about curiosity:

“The more curious we are, the more we learn and recall later about our learning. Moreover, curiosity is more strongly linked to student success than IQ or persistence (Shah et al., 2018). Bryan Goodwin, Building a Curious School, p. xxii.

Think about that phrase…more strongly linked to student success than IQ or persistence. Wow.

💡When Facilitating Adult Learning

This summer the ABPC staff and a small group of educators who participate in our networks met to plan the learning for this upcoming year. As part of that planning, we looked at both the research about adult learning (“andragogy”) and effective facilitation.

Malcolm Knowles, who coined the phrase andragogy, identified six important facets of adult learning theory:

- The learner’s need to know;

- The learner’s self-concept;

- The learner’s experience;

- The learner’s readiness of learn;

- The learner’s orientation to learning; and

- The learner’s motivation to learn.

All of these factors are connected in some way or other to curiosity, and it is the facilitator’s job to “hook” their participants so they want to learn more. Whether it’s learning more about an historical event or an exercise technique so we can be healthier, our curiosity about the subject can help the learning “stick.”

Staying with facilitation a bit longer, I turned to noted corporate facilitator Roger Schwartz, who also considers curiosity to be a powerful tool, particularly when dealing with conflict. In coaching and facilitating situations we want to promote the sense that…

“You’re curious about others not because you want to use their response to show how they’re wrong, but because you want to appreciate the situation from their perspective.” — Schwartz, The Skilled Facilitator, Third Edition, p. 72.

Schwartz also reminds us that genuine curiosity requires intentionality and practice:

“Developing a mindset of curiosity is more difficult than understanding the mechanics. In challenging situations, we usually believe that we understand and are right; those who disagree don’t understand and are wrong…. When we’re not curious, we can easily become frustrated, as we wonder why others don’t understand what’s obvious to us.” p. 66

💡When Coaching Colleagues

Of course, I couldn’t write a blog about curiosity without turning to one of the great thinkers about coaching, Jim Knight. Curiosity is embedded in most of his seven partnership principles.

Knight reminds us that “during partnership coaching conversations, coaches create a setting in which collaborating teachers feel comfortable saying what they think.”

“Coaches are curious to understand, and they make sure the conversation focuses on the teachers’ concerns. In this way, they get to hear the real truth…Coaches ask questions of their partners because they’re more concerned with getting things right than with being right. Therefore, they ask good questions to which they don’t know the answers —and they listen for the answers.

“For example, when they ask, ‘What evidence did you see that shows that your students are learning?’ they want to know what the teacher thinks, not guide the teacher to see what they see. (Coaches) stop persuading, and they start learning.” — “What Good Coaches Do” Educational Leadership, Oct. 2011.

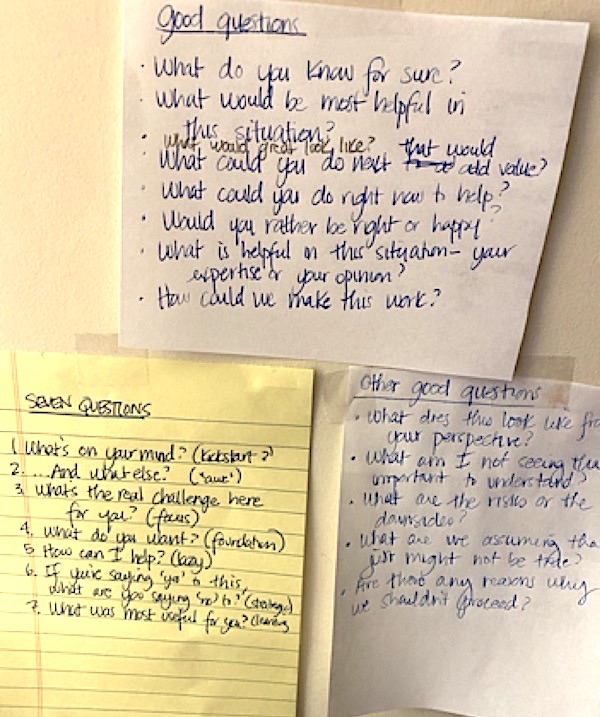

Another great coach, Michael Bungay Stanier, in his book The Advice Trap, suggests that good coaches stay curious a little longer and “rush to action and advice-giving a little more slowly.” Stanier suggests seven questions that can tap into a coachee’s curiosity, beginning with “What’s on your mind?”

To help me include curiosity when coaching, I have a “wall of questions” by my desk, including Stanier’s seven questions.

💡To Expand Our Thinking & the Thinking of Others

The ABPC’s first-ever online book study features a book by Wharton professor Adam Grant titled Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know. Grant encourages his readers to begin to think more like a scientist by embracing uncertainty, curiosity, and humility:

“When we’re trying to persuade people, we frequently take an adversarial approach. Instead of opening their minds, we effectively shut them down or rile them up. They play defense by putting up a shield, play offense by preaching their perspective and prosecuting ours, or play politics by telling us what we want to hear without changing what they actually think. I want to explore a more collaborative approach—one in which we show more humility and curiosity, and invite others to think like scientists.” p. 102

Grant adds that humility is critical if we want to connect with others: “Many communicators try to make themselves look smart. Great listeners are more interested in making their audiences feel smart. They help people approach their own views with more humility, doubt, and curiosity.” p. 158

💡To Escape the Trap of High Conflict

My latest read, High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out, by Amanda Ripley (watch for my review in a few weeks) is full of references about curiosity. Curiosity can defuse a tense situation if we display it honestly and authentically. Curiosity can both help deepen understanding and move a conversation from “I’m right and you’re wrong” to a more insightful and productive dialogue.

Ripley suggests that curiosity is a necessary component to active listening: “Getting better at listening means getting more curious – and making people around you more curious. It’s more than a skill; it’s a skeleton key.” p. 294.

Noting that “questions, asked with genuine curiosity, can make conflict suddenly interesting again,” she suggests eight questions to help defuse conflict:

- What is oversimplified about this conflict?

- What do you want to understand about the other side?

- What do you want the other side to understand about you?

- What would it feel like if you woke up and this problem was solved?

- What’s the question nobody’s asking?

- What do you want to know about this controversy that you don’t already know?

- Where do you feel torn?

- Tell me more. (p 295)

I think #5 – what’s the question nobody’s asking – could be a real curiosity-sparker and lead to some intriguing “elephant in the room” conversations.

Curiosity: Nature’s Rx for Anger Management?

I’m convinced that if more of us approached situations with a curious mind and nature, we’d learn more, be better friends and humans, and be healthier as well. I hope these tips will help you learn more and defuse tense situations. And, I invite you to share additional methods you might think of to be more curious and less certain and set in our ways.

0 Comments on "Curiosity Can Be Our Superpower"