Reading and writing are gateways to success in life. Yet far too many students leave school without completely mastering these two very important skills.

Reading and writing are gateways to success in life. Yet far too many students leave school without completely mastering these two very important skills.

That’s why I read with interest Doug Lemov’s book, Reading Reconsidered: A Practical Guide to Rigorous Literacy Instruction. Lemov and coauthors Colleen Driggs and Erica Woolway are all affiliated with Uncommon Schools, a network of charter schools in the Northeast serving high poverty students.

The book is written primarily for educators working with students in upper elementary school through high school. The authors’ purpose for writing the book is to help more teachers successfully prepare ALL of their students in this age range with the literacy skills they need to successfully pursue college and careers.

Reading at the core level

Although we are all aware of the proliferation of “new literacies” – podcasts are all the rage, audiobooks abound, and a graphic novel, New Kid, just became the first book in that medium to win the Newbery Award – Lemov and his co-authors argue that traditional reading is still THE fundamental:

Words, especially the written variety, remain the primary currency of ideas, and the diligent study of reading is the diligent study of idea creation and development, so the urgency of making the teaching of reading in American schools as effective and rigorous as it can be must always be at the forefront of the work – and every teacher plays a role. Every student must glimpse, as much as possible, the power that comes from the world that reading can bring to light (p. 3)

The authors identify four “cores” to successful reading:

- Read harder texts

- Close-read texts rigorously and intentionally

- Read more nonfiction more effectively

- Write more effectively in direct response to texts

The book is organized around those four cores, along with an abundance of tips, videos and ideas to support implementation. One of the most valuable resources in the book is the large number of short videos giving its readers a front-row seat into teaching practices. Other resources include the appendix with an extensive glossary of ELA/literacy terms. Additionally, tables throughout the book offer strategies varying from building autonomy to key prompts that deepen student thinking.

While most of the techniques suggested in the book lean toward direct and explicit instruction – something the authors believe is necessary to ensure that students understand and possess the skills needed to be successful readers and writers – the type of teaching advocated by the authors does not seem to be robotic or simply script-based. Their core argument is that If students don’t possess the vital skills of decoding, fluency, and a robust vocabulary their comprehension will be limited at best.

Background Knowledge is Essential

In addition to mastering reading, students require background knowledge to be successful. The book quotes Daniel Willingham, a cognitive scientist at the University of Virginia and a leader in the “content matters” conversation:

Once kids are fluent decoders, much of the difference among readers is not due to whether you’re a ‘good reader’ or ‘bad reader’ (meaning you have good or bad reading skills). Much of the difference among readers is due to how wide a range of knowledge they have. If you hand me a reading test and the text is something I happen to know a bit about, I’ll do better than if it happens to be on a subject I know nothing about…Teaching content IS teaching reading (p. 50)

Because most of the students who attend Uncommon Schools come from challenging situations where exposure to rich sources of information about the world is often limited, building background knowledge is essential. And even the most accomplished reader will struggle with content with which they are unfamiliar. For example, asking an avid baseball fan in the United States to read a book about the sport of cricket would pose a background knowledge challenge – chances are they would have little familiarity with the game.

Vocabulary Instruction: Breadth and Depth

In the book, the authors quote E.D. Hirsch Jr.’s study finding students need to learn 43,000 words on average to be ready for college. Moreover, it is not just about learning the words; it’s also about deeply understanding the words, so that the reader both understands and uses those words correctly.

To help students reach Hirsch’s threshold, the book outlines two strategies: Explicit and Implicit Vocabulary Instruction. When reading difficult texts, students will encounter words unknown to them. To prepare them for the text, teachers need to be explicit. They should identify and explain the terms in advance. Or, if the class is reading out loud, or listening to the teacher read, the teacher should stop at those challenging words to make sure that students understand the meaning. At times, some words may require the teacher to teach a mini-lesson to students. At other times, it may be sufficient for teachers to give a short student-friendly definition to prevent losing the “flow” of the story.

To help students reach Hirsch’s threshold, the book outlines two strategies: Explicit and Implicit Vocabulary Instruction. When reading difficult texts, students will encounter words unknown to them. To prepare them for the text, teachers need to be explicit. They should identify and explain the terms in advance. Or, if the class is reading out loud, or listening to the teacher read, the teacher should stop at those challenging words to make sure that students understand the meaning. At times, some words may require the teacher to teach a mini-lesson to students. At other times, it may be sufficient for teachers to give a short student-friendly definition to prevent losing the “flow” of the story.

Implicit Vocabulary Instruction helps students develop the skills to learn words they encounter during reading. The three goals of this form of instruction are: (1) maximizing the “absorption rate of new words by cultivating attentiveness to unknown vocabulary words during reading;” (2) Increasing background knowledge; and (3) Increasing comprehension (p. 271).

If Explicit Instruction is, roughly, a set of tools to teach words directly, Implicit Instruction is a set of tools designed to maximize the number of words absorbed from reading. There are many arguments that contest which one of these methods is superior. The answer, we think, is that they are both necessary. (From Lemov’s Field Notes blog, posted during the final editing of Reading Reconsidered.)

The authors offer an abundance of strategies for using both explicit and implicit vocabulary instruction. At times, I found myself turning to a dictionary to ensure that I understood all the words they introduced!

My Big Takeaway

I found a good deal of useful information and ideas in the book. I also worry about killing the joy of reading for students. It’s all about balance. Student must be able to decode, read fluently, and build their background knowledge so they can comprehend even the most difficult of texts. At the same time, we also must develop a lifelong joy of reading. It’s about a good balance of both strategies.

As I write this, I’m reminded of why teaching requires a lot of heavy lifting! We need to pay attention to building those basic skills and expanding vocabulary and background knowledge. First and foremost, we need to hold high expectations both for those who teach and for those who are there to learn. That said, we also need to expose students to rich literature while giving them opportunities to choose books and genres and even modalities that particularly appeal to them.

I would encourage teachers and all of us who think a lot about the best ways to help students learn and grow “broadly and deeply” to explore not just one theory but a variety of theories and approaches to literacy instruction. I think of this as the “Yes, and…” approach – my favorite.

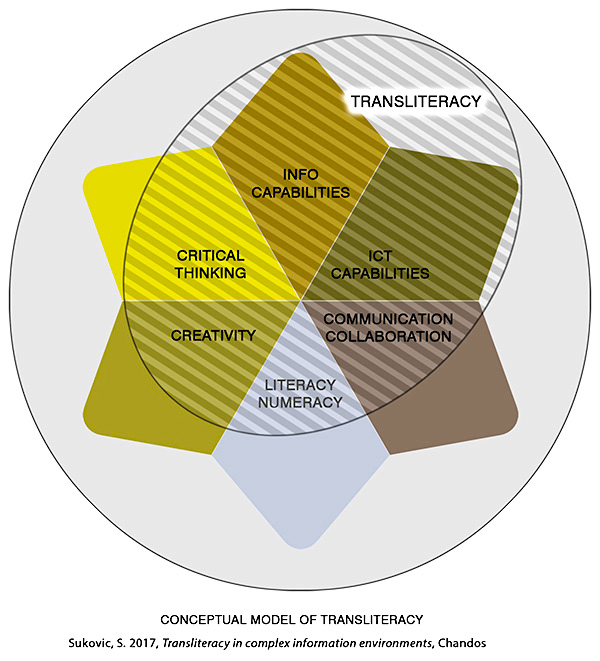

The dimensions of literacy are expanding and morphing into new shapes as our students become more and more immersed in digital technologies and display-based communication, information gathering, and “meaning making.” We are not, I hope, moving toward a “post-literate” world but toward a fascinating “multi-literate” world, and our kids need to be ready.

Feature image: The cover of New Kid, written and illustrated by Jerry Craft, winner of the 2020 Newbery Medal for Children’s Literature.

0 Comments on "Bringing Rigor and Balance to Reading Instruction"