By Cathy Gassenheimer

By Cathy Gassenheimer

Executive Vice President

Alabama Best Practices Center

Imagine this for a moment:

High schools populated by teachers and students who can’t wait to get to school every day to collaborate, discover, create, and learn.

An impossible dream? You might not think so after learning what authors Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine have to share.

Mehta, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, and Fine, a faculty member at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education (UC-San Diego), spent six years learning about the current state of high school education. They visited 30 schools and selected four of them for a “deep dive” – spending almost a month in each one. They write about their conclusions in a recent book, In Search of Deeper Learning: The Quest to Remake the American High School, published by Harvard University Press.

“This book is a remarkably fresh, balanced, research-based look at American high schools. It is a powerful provocation for discussing what a good high school is, and what good teaching looks like. Every high school faculty should use it as a common read: it will open minds and shatter stereotypes.” – Ron Berger, Chief Academic Officer, EL Education

“This book is a remarkably fresh, balanced, research-based look at American high schools. It is a powerful provocation for discussing what a good high school is, and what good teaching looks like. Every high school faculty should use it as a common read: it will open minds and shatter stereotypes.” – Ron Berger, Chief Academic Officer, EL Education

While the education scholars did find some pockets of excellence as they searched for examples of “deep learning,” for the most part they captured a bleak picture of what high school students endure daily in schools across America.

Their findings confirm data from the National Center for Education Statistics showing that “the longer students are in school, the less engaged they feel: 75 percent of fifth graders feel engaged by school, but only 32 percent of eleventh graders feel similarly” (pp. 3-4).

What is Deeper Learning?

The cure for this dramatic decline in engagement? The authors call for a transformational shift away from the emphasis on breadth over depth that characterizes most high school classrooms and toward an approach to teaching and learning that values student agency over content coverage and creates a desire to go deep and discover the things that matter most.

Deeper learning moves us away from practices that skim the surface of knowledge, Mehta and Fine conclude, and toward a style of teaching that values collaboration and collective efficacy and puts a premium on student engagement and interest.

The authors identified three key attributes of deeper learning.:

- Mastery because you cannot learn something deep without building up considerable skill and knowledge in the particular domain;

- Identity because it is hard to learn anything deeply without becoming identified with the domain; and

- Creativity because moving from taking in someone else’s ideas to developing your own is a big part of what makes learning ‘deep.’

In addition to these key attributes, Mehta and Fine point to the importance of community – in the classroom and across the school – “for it is in community that this learning frequently takes place.” (p. 299)

Profiling Four Different Types of High Schools

In the first two-thirds of the book, the authors profile three types of charter schools and one comprehensive high school. Identified with pseudonyms, the three types of charter schools profiled included:

- John Dewey High School: a project-based themed school.

- No Excuses School: Tight discipline and control, with teacher directed tasks aimed toward mastery.

- International Baccalaureate School: Centered on academic and extracurricular performance tasks where student mastery is expected.

The comprehensive high school profiled, using the pseudonym Attainment High, is described as “a best case scenario of apprising the possibilities of a comprehensive high school” (p. 197) with the following characteristics:

- has a significant base of highly educated parents,

- is well funded,

- has experienced teachers, many who describe the school as their “dream job,” and

- has some diversity both economically and racially.

In all four high school case studies, the authors found silver linings pointing to deeper learning, but also certain flaws. They worried about the consistency of rigor at Dewey High, which sometimes privileged the projects over the commitment to rigor. At No Excuses School, teachers and administration began to worry that the rigid nature of the school did not prepare students for the more flexible environment of college. The authors identified the IB School as coming closest to their vision of deeper learning but noted that not all IB schools require ALL students to complete the rigorous International Baccalaureate program and diploma.

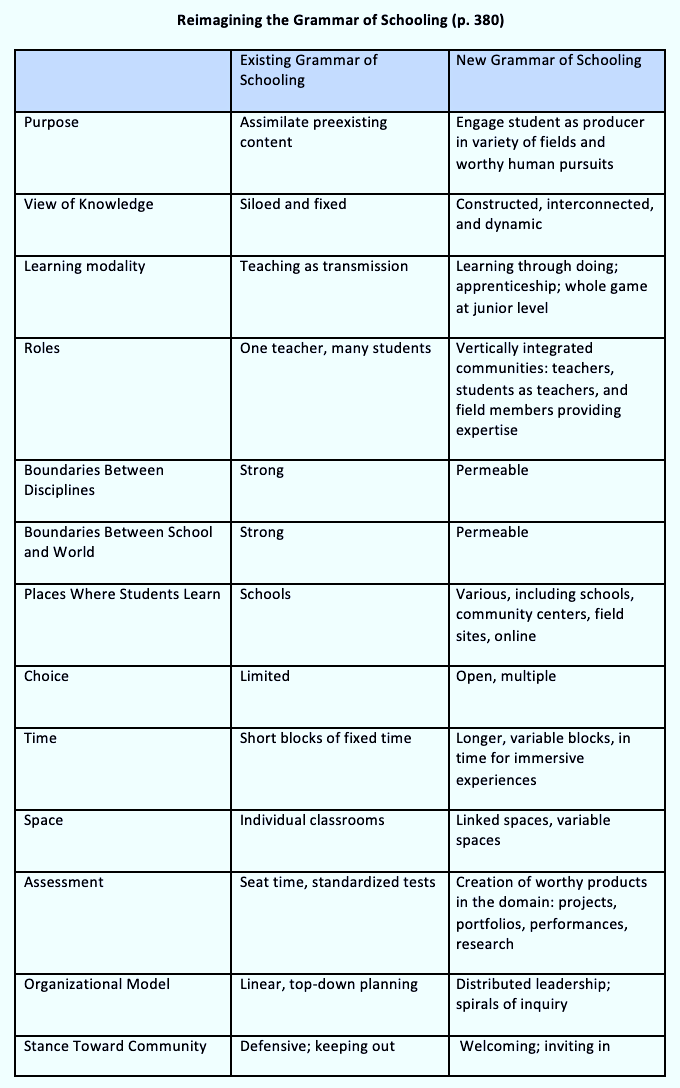

The authors also conceded that Attainment High was somewhat of an outlier and more prosperous than many comprehensive high schools. And, even though many of its extracurricular courses displayed deeper learning, much of the teaching and learning in the core disciplines still operated under the current “grammar of schooling” (see their table below).

In short, the authors noted that Attainment High “was in some ways divided against itself—the assumptions enculturated in the traditional grammar of schooling were in conflict with the way the school otherwise wanted to treat its students” (p. 251).

Deeper Learning in the Margins

A pattern emerged in the four schools Mehta and Fine studied in depth. Engagement happened most often in elective courses: arts, music, electives, and extra-curricular. Because there were no mandated pacing guides for these courses teachers could design learning that offered depth over breadth. Choice was also an important factor – students opted into these courses outside the core.

Most of the opt-in courses were performance-based (think mastery), connected to students’ specific interests, and involved creativity. In fact, the authors devote almost an entire chapter to a theater class at Attainment High where students mounted a production of a complex play, The Servant of Two Masters.

Most of the opt-in courses were performance-based (think mastery), connected to students’ specific interests, and involved creativity. In fact, the authors devote almost an entire chapter to a theater class at Attainment High where students mounted a production of a complex play, The Servant of Two Masters.

In this theater class, the three attributes of deeper learning were augmented by purpose, passion, and precision from the selection of the play all the way to the performance. Apprenticeship was also a key factor as teachers and local actors were available to the student actors.

“Different forms of learning were used to triangulate Servant—direct adult instruction, collective student analysis of videos of previous productions and interpretations of stock characters, individual research by actors (both text and video), and particular student roles (the dramaturgs) in which selected students developed a specialized expertise that was then shared with the group” (p. 285).

Moving Deeper Learning from the Margins

Based on their extensive research and observations, Mehta and Fine developed the following thesis for the book: “We need to change student learning, so we need to change schools, so we need to change systems” (p. 363).

Changing the grammar of schooling, a term created by Larry Cuban and David Tyack, is long overdue, they say. To enable deeper learning, schools need to move away from sole reliance on age-specific classrooms, subject-specific courses, and teacher-led classrooms with class sizes of about 25 students.

The pattern in the current grammar of schooling, they explain, “is that there is a prespecified body of knowledge to be covered, students spend some period of time learning to remember some key attributes of this body of knowledge, there is an assessment (either a test or a writing assignment), and then the process repeats with a new topic. At its best, this process builds some knowledge in a domain; at its worst, it becomes a game of ‘cover-remember-forget-repeat.” (pp. 198-199).

Five presumptions are necessary to make the shift to deeper learning:

- View students as “purposeful, curious, capable beings who have interests that can be developed and who value being treated as responsible people.”

- Provide students with some choice and agency over their learning, “coupled with guidance from more experienced students and adults” (think apprenticeship and academically rigorous CTE models).

- Create a community of learners where students are connected to people from whom they can “learn and relate.”

- Build connections: student-to-student; student-to-teachers and experts; student-to-content; student-to-mentors/experts; student-to-self (metacognition).

- Include adults in this shift: “Adults need purpose in their work, they need both choice and community, then need time to work with one another and to connect with knowledgeable others beyond the school walls, and they need an opportunity to revise as fields evolve, as the world changes, and as new ideas become salient.” (p. 379)

What Deeper Learning Looks Like: A Different Stance

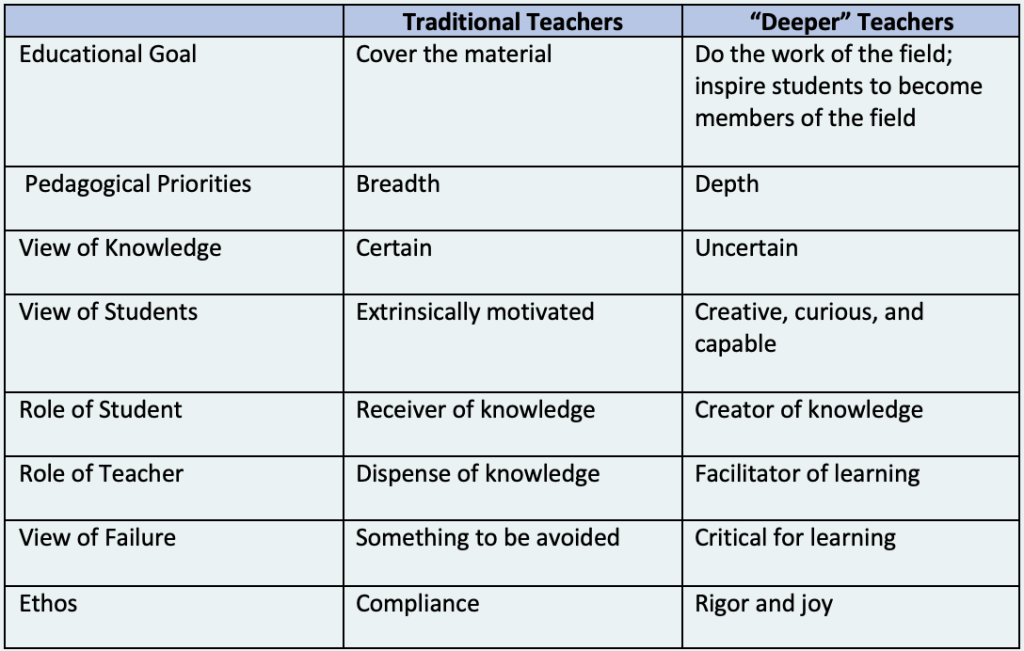

Making this fundamental shift in the grammar of learning requires structural and dispositional change in addition to adding more knowledge and skills to a teacher’s toolbox. One of the authors’ key recommendations involves an overhaul of teacher education where teacher candidates both learn about deeper learning strategies and are apprenticed to deeper learning master teachers. (Table, p.351)

Connecting to Post-Secondary Education, Work, and Jobs

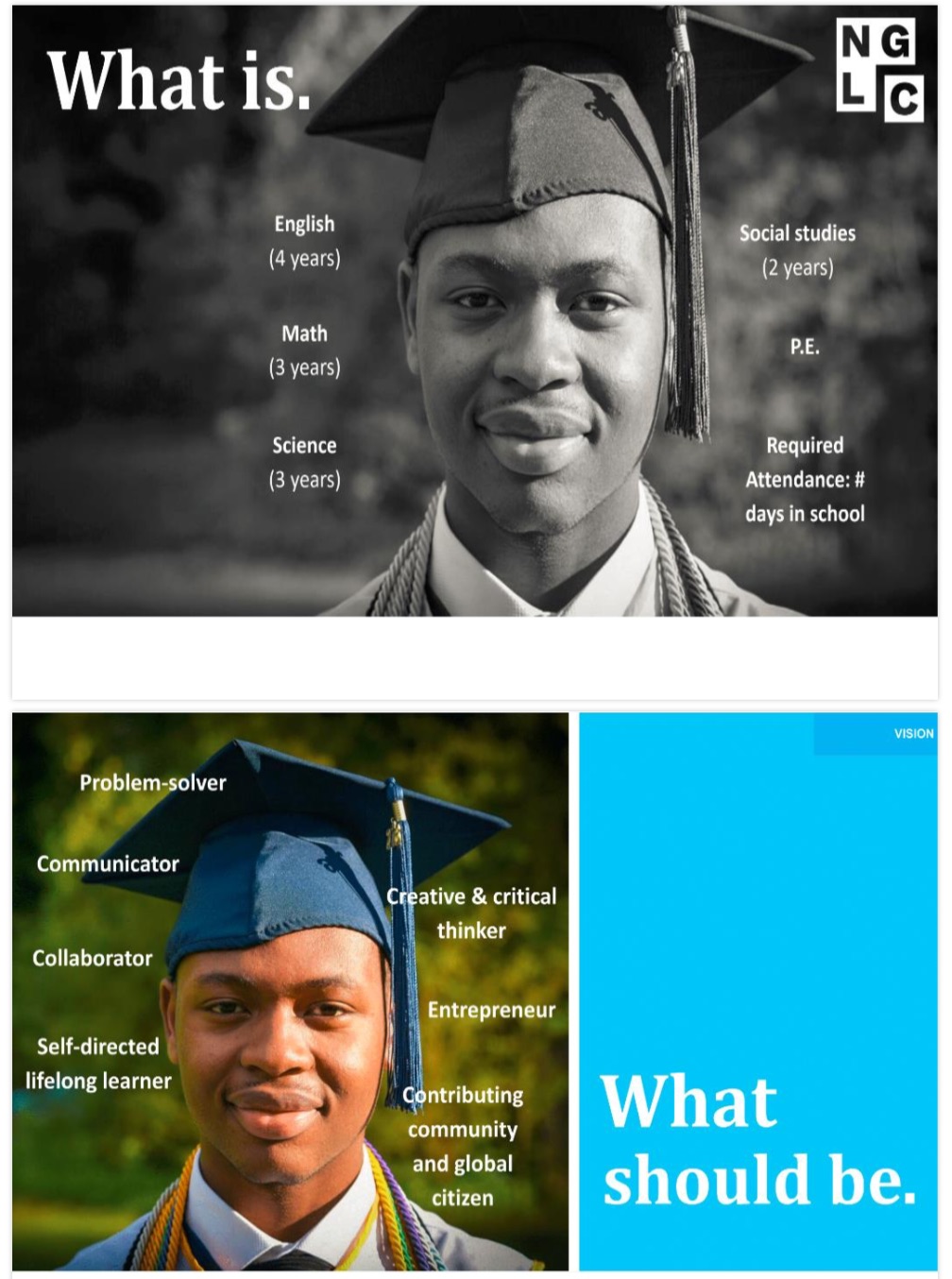

As I read the book, I kept thinking about our ever-changing world dynamic. No longer can anyone claim that knowledge is fixed or that we can prepare students for just one job when most will have more than ten over their lifetime.

The following video (or videos) quickly capture the disconnect between current US schooling and what students need to be successful in the future – and right now.

► Shift Happens (2018 remix by educator Katy Scott)

► Shift Happens (2021 perspective)

If we want to ensure that today and tomorrow’s students can respond to an increasingly complex world faced with climate change, domestic and international terrorism, current and future pandemics, the rise of artificial intelligence, and a rapidly evolving workplace, we must embrace deeper learning.

Students need to learn how to learn so they can master new concepts and ideas. The prime directive for high schools today needs to be: Teach students how to learn for a lifetime.

A key part of learning needs to be collaborative, so students learn how to effectively work with others. A heavy emphasis on written and oral communication and listening skills is essential. As Harvard’s David Perkins notes, students need to learn not by passively listening to a teacher tell them what they need to know, but rather by playing the whole game, junior version.

If we can change our systems and make these shifts – adopt the “new grammar” described by Mehta and Fine and embrace deeper learning – we will see many more high schools where students and teachers can’t wait to get to class every day.

Resources:

The Quest to Remake the American High School: A Conversation with Jal Mehta – NCEE CEO Anthony McKay talks with co-author Mehta about this book and his predictions about the future of secondary education in America. (Text and video)

Do School Plays Lead to PhDs? – Co-author Sarah Fine discusses the impact of the arts (specifically the play production I mentioned above) in this article at the Reasons to Be Cheerful website.

Designing for Deeper Learning: Mastery, Identity, Creativity & A New Grammar Of Schooling – Slides from Mehta’s presentation to the Latvia Education Technology Conference (August, 2021 – PDF)

0 Comments on "The Quest to Remake the American High School"