When Cathy Gassenheimer sent me a post from Susan Cain’s Quiet Revolution website entitled, “6 Illustrations That Show What It’s Like in an Introvert’s Head” by Liz Fosslien and Mollie West, my first response was “Yes!” It’s probably the best explanation of what it means to be an introvert that I have seen in a while.

Why did Cathy send along this article? First, she knows I’m an introvert. In fact, I wrote about that here at the ABPC blog a few years ago. Second, she knows that we have many students who are introverts, too, and they are always at risk of being overlooked in our busy classrooms. These are not the kids who demand our attention. And there are many of them.

Reading through this article, while all six illustrations are as true as they can be, three really stuck out to me, both as an educator and as an introvert married to and surrounded by extroverts. Let me share some of my thoughts, in the hope that we can all raise our awareness of the challenges and gifts that “introverts” bring to the table.

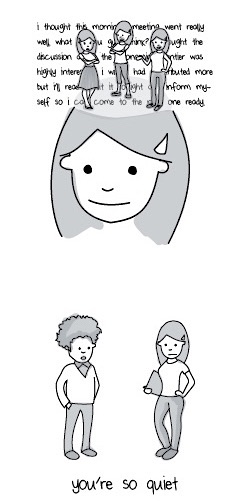

1) Introverts are easily over-stimulated

Fosslien and West’s second illustration/explanation attempts to portray why introverts seem to be drained after interactions, instead of energized: “…introverts require less stimulation from the world in order to be awake and alert…[therefore], introverts are more easily over-stimulated.”

When I reflect on this, I think about those students and teachers who need a quiet working environment. I myself have been known to receive a task and then leave the area to find just such a place. As an introvert, I have a hard time concentrating on my task at hand if there is too much going on around me. Music can help, and I will often use my earbuds to try and block out those around me.

When I reflect on this, I think about those students and teachers who need a quiet working environment. I myself have been known to receive a task and then leave the area to find just such a place. As an introvert, I have a hard time concentrating on my task at hand if there is too much going on around me. Music can help, and I will often use my earbuds to try and block out those around me.

Thinking about our students in the classroom, that child who is quiet most of the time…how often has that student seemed unable to concentrate? They are trying hard, but they just can’t focus. They may be getting frustrated and snippy. They may even ask if they can leave the classroom or listen to their music while they work.

It’s probably a good bet that they have become over-stimulated and are trying to find a way to stay on task. Consider giving these students a quiet spot to work. Try not to become upset with them. Instead, help them find ways to reduce that stimulation. Support them as they learn coping skills so that they can still actively participate with the group.

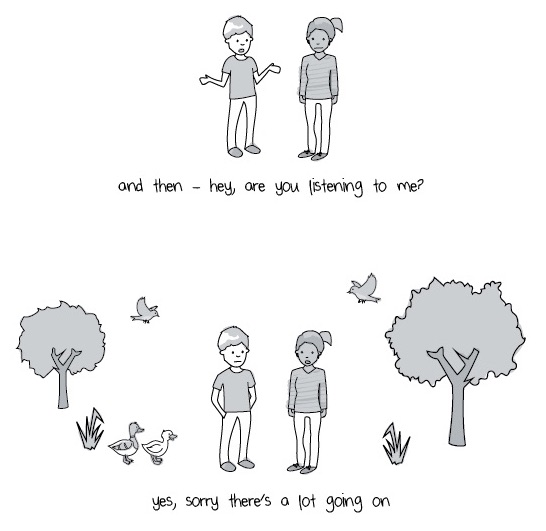

2) Introverts process EVERYTHING!

This brings me to my next point. The fifth illustration/explanation attempts to dig deeper into why introverts are easily over-stimulated. “Introverts process everything in their surroundings and pay attention to all the sensory details in the environment, not just the people.”

Because we introverts tend to treat every interaction with the same level of intensity, we can get over-stimulated quickly. In education, we are taught to come up with great, attention-getting and engaging lessons. We create choice boards and multilayered projects. We require students to work in groups to complete part or all of an assignment that they are given. And then we become frustrated with the student or students who are “daydreaming” or who can’t make a decision on what they want to choose to work on. We tell them to hurry up and decide. We lose patience because they seem indecisive.

Unfortunately, the truth is that these are probably introverted students and they are trying to process all the information given so they can make a decision. It’s not that they don’t want to decide, sometimes they just can’t…the choices are too overwhelming.

Unfortunately, the truth is that these are probably introverted students and they are trying to process all the information given so they can make a decision. It’s not that they don’t want to decide, sometimes they just can’t…the choices are too overwhelming.

This explanation makes me think of a very good teacher friend of mine. She is an extrovert and her classroom is a great example of how project-based learning can work. However, I can remember having conversations with her about the students in her class who didn’t seem to be thriving. She would become upset because these students might change their minds mid-project and want to alter what they were working on. Or worse, they couldn’t seem to get started on anything and kept asking questions about the project, including asking for additional time to complete it.

After several of these conversations, I began to realize that she may be dealing with introverted students. I suggested she take her next project and break it into stages…students would receive the next stage once they had completed the previous stage. I also asked her to limit some of the choices. Instead of a “you just decide what you want to do”, I suggested she give students 3-4 ideas to choose from. She agreed and we planned the new project to reflect my suggestions.

I checked in with her throughout the project to see how it was going, and she told me that she was pleasantly surprised that by limiting the amount of work she offered at one time, she actually had more engagement. By limiting, or structuring choice, she was able to help her introvert students focus better and thus they did not feel quite as overwhelmed. These students were able to contribute more to conversations and to their groups because they weren’t as busy processing everything for the project.

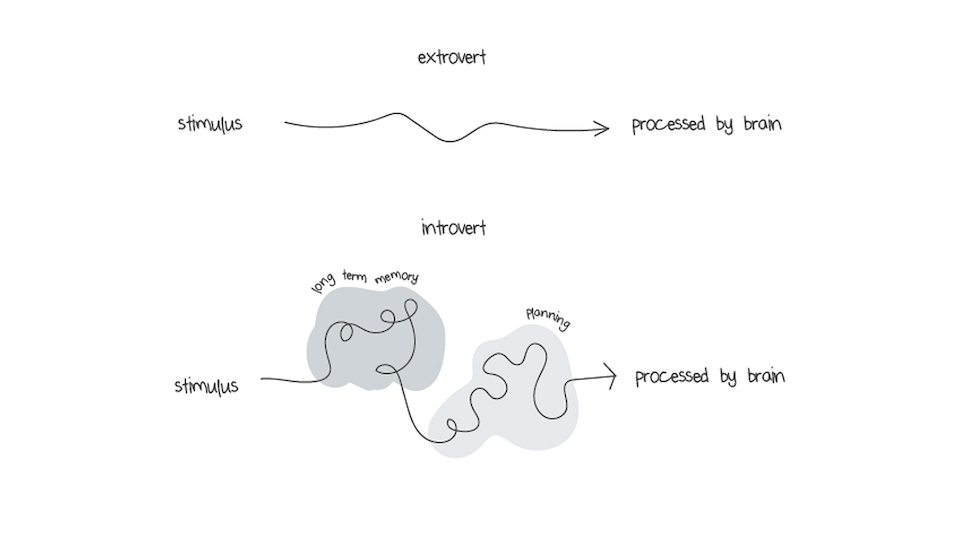

3) It takes longer for introverts to process information

Finally, according to Fosslien and West, “…introverts have a longer neural pathway for processing stimuli…In other words, it’s more complicated for introverts to process interactions and events.” According to the authors, when introverts are processing new information, they are also “attending to their internal thoughts and feelings at the same time.”

We introverts don’t just receive information, process it, and produce an output. We take in the new information, reflect on what we know about the information so far, decide how the new information differs from the prior knowledge, and then add in how the new information makes us feel. Once that is all done, we then decide if we are going to actually comment on the new information or wait for additional input.

And while all this is happening, while we are having this internal dialogue with ourselves, the outside world (extroverts) are either commenting that we are too quiet or taking too long to make a decision. They attempt to hurry us along in our decision-making process. Of course, this leads to frustration for both parties as introverts may get overwhelmed and the extroverts may feel stagnant.

And while all this is happening, while we are having this internal dialogue with ourselves, the outside world (extroverts) are either commenting that we are too quiet or taking too long to make a decision. They attempt to hurry us along in our decision-making process. Of course, this leads to frustration for both parties as introverts may get overwhelmed and the extroverts may feel stagnant.

In the classroom, this can reveal itself in many different ways. Perhaps you have a group of students working and they suddenly complain that one of the students won’t contribute to the conversation. When asked, the student explains that they are still thinking about what everyone is saying. The other group members complain that the student doesn’t need to think about it, they just need to give their input.

Without time to process, introverts tend to feel as if their input isn’t valuable. And when prodded, they may just shut down and close themselves off because this is better than giving an opinion or giving input that they may later have to take back after they have had time to reflect.

Helping our extroverted students understand that some students need more time to process information may also help them learn to be more reflective, thus resulting in better, deeper conversations in the classroom. Allowing introverts that little extra time they need to process information can only lead to a more reflective learning environment.

Helping our students understand themselves

Of course, not every introvert or extrovert will fall neatly into these categories. Like with most human behaviors, there’s a wide range. As educators, the important thing for us to remember in our planning is that introversion and extroversion are important factors to consider, along with learning styles and other differentiation factors.

With an estimated 50% of our population being introverted to some degree, it is not nearly as rare as we would like to believe, and learning to help both extroverted and introverted students understand more about themselves and each other will only enhance our learning environments.

So as you plan for the school year, consider giving a shortened version of the Briggs-Meyers test along with your learning styles inventory and other information gathering tools. Not only will this help you better serve your students, but it will help your students better understand themselves.

Note: Susan Cain is the author of the bestseller Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking. These illustrations appear at her Quiet Revolution website.

DeAnna Miller (@DMiller0502) has been a teacher, instructional coach, and assistant principal during her 10+ year career in education. She worked as a middle school English teacher and Instructional Partner in Enterprise City before shifting into administration. This fall, she became the Assistant Principal at Holly Hill Elementary, also in Enterprise. (Learn more about DeAnna.)

0 Comments on "How Can We Be Sure We’re Reaching Our “Quiet Kids”?"