Now more than ever, we need to focus on social and emotional learning. The pandemic has caused fissures in our normal day-to-day lives, and the emotional impact seems to affect school-aged children disproportionately.

That’s why I am so intrigued with what research scientists continue to discover about the brain, particularly when it comes to controlling emotions and stress.

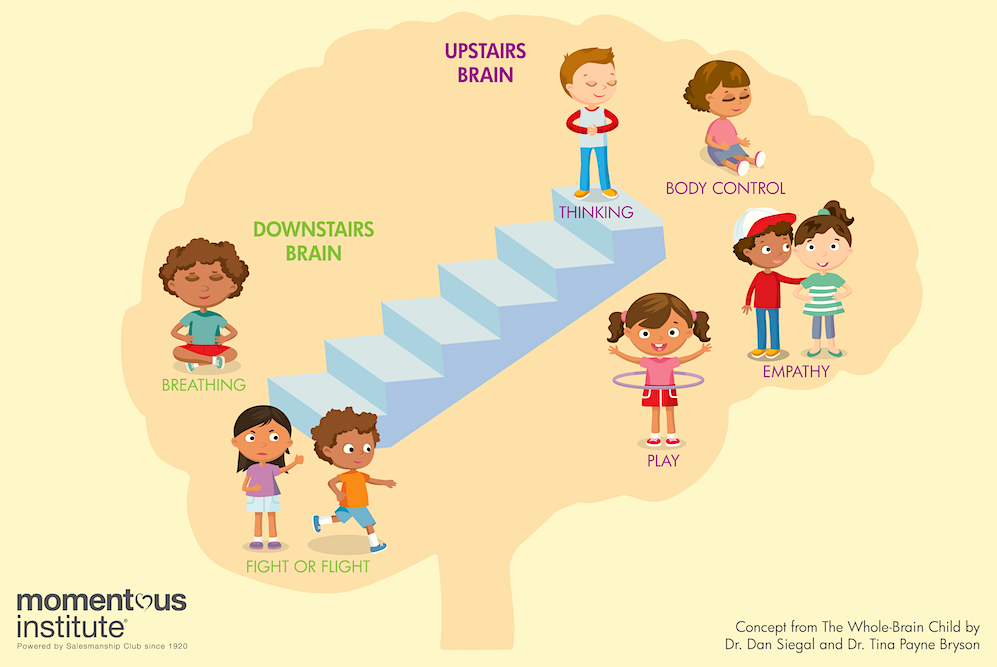

In our ABPC professional learning networks, we’ve learned about the concept of the “upstairs and downstairs brain,” a metaphor for how humans react to stress and fear. When faced with something unexpected, an affront, or something that puts us on guard, we sometimes succumb to our “flight-freeze-freeze” mode, sometimes called the “downstairs brain.” At other times, we can resist the pressure, remain calm and function in our “upstairs brain.”

When a new book about the brain arrived, I made reading it a priority. Its size and title intrigued me: 7 and a Half Lessons About the Brain, by Lisa Feldman Barrett. The book was smaller than the “standard” size, and it was only 125 pages long, excluding the appendices and index.

When a new book about the brain arrived, I made reading it a priority. Its size and title intrigued me: 7 and a Half Lessons About the Brain, by Lisa Feldman Barrett. The book was smaller than the “standard” size, and it was only 125 pages long, excluding the appendices and index.

As I looked at the book and the table of contents, a series of questions emerged:

► Why 7-1/2 lessons and not 7 lessons or eight lessons?

► How will this book relate to social and emotional skills?

► Who is the author and what are her credentials?

The author answered the first question on the second page of the book. She noted that each chapter should be viewed more as an essay on a particular facet of the brain. “The opening essay tells a story of how brains evolved, but is just a brief peek into a vast evolutionary history—hence, half a lesson.”

Before I go into detail about the book, a note about Lisa Feldman Barrett’s writing style: She is clear, concise, and explains complex issues in terms in easy-to-understand ways. And, she’s not afraid to take aim at several “understandings” about the brain that she contends are actually misunderstandings. In short, I found her writing to be provocative and intriguing.

Barrett’s Background

According to the dust cover of the book, Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD, is “among the top 1 percent most-cited scientists in the world for her revolutionary research in psychology and neuroscience. She is a University Distinguished Professor at Northeastern University with appointments at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School.” For more information about Dr. Barrett, this link will take you to her website.

Your Brain is Not for Thinking

In her “half-essay,” Barrett grabs the reader’s attention with this title: “Your Brain is Not for Thinking.” Barrett calls upon research that shows the brain is actually tasked with keeping you healthy, balanced, and alive. She describes this process as “body budgeting,” or allostasis (if you want to read the technical definition of allostasis, click here). To manage allostasis, the brain works to predict your “energy needs before they arise so you can efficiently make worthwhile movements and survive” (p. 10).

This concept made sense to me. I remembered books I had read in the past, like Brain Rules by John Medina, that connect allostasis to our hunter-gatherer days. If our brain isn’t looking out for us, we won’t be able to think about matters beyond survival. We might be dead!

A: Brains didn’t evolve so you can think, feel or see. They evolved to control bodies. Everything your brain does – think, feel, see, hear, etc. — it does in the service of controlling your body. This is your brain’s most important job. Understanding this illuminates mysteries like: How are your mind and body linked? How does chronic stress seep under the skin and make you sick? Why are physical illnesses like heart disease and Parkinson’s disease so similar to mental illnesses like depression? And why there is a growing epidemic of depression and anxiety around the world?

— from an interview with Lisa Barrett at her Amazon book page.

We Have One Brain, Not Three

The second essay blew up one of my notions about the brain, and I’m still wondering about it. Barrett pointed to past science thinking that suggests the brain has three layers: one for surviving, one for emotions/feelings, and one for thinking. This theory is known as the “triune brain.”

Not so fast, argues Barrett. “The triune brain is one of the most successful and widespread errors in all of science” (p. 15). Instead, using advanced techniques not previously available (involving looking inside neurons and genes), scientists have learned that “evolution does not add layers to brain anatomy,” but rather as brains get larger, “they reorganize” (p. 18).

Barrett continues: “The real story is that during the course of evolution, certain genes mutated to cause particular states of brain development to run longer or shorter times, producing a brain with proportionally bigger or smaller parts.

“So, you don’t have an inner lizard or an emotional beast-brain. There is no such thing as a limbic system dedicated to emotions…Anything you read or hear that proclaims the human neocortex, cerebral cortex, or prefrontal cortex to be the root of rationality, or says that the frontal lobe regulates so-called emotional brain areas to keep irrational behavior in check, is simply outdated or woefully incomplete” (p. 24).

Flipping Your Lid

As I read this, I recalled the work of Dr. Daniel Siegel, a clinical professor of psychiatry,at the UCLA School of Medicine. His hand model of the brain is one that we’ve used extensively this year in our professional learning networks. Take two minutes to watch this short video:

This video was recorded back in 2012, most likely before the new findings that Lisa Feldman Barrett refers to in her book. Yet, I find his explanation to be extremely helpful, and his suggestions for how to avoid “flipping your lid” useful.

I’m actually writing this blog post to address the cognitive dissonance that I’m experiencing when faced with the seemingly disparate thinking of Barrett and Siegel. Not being a scientist, I’m out of my league when it comes to judging whether their views are completely at odds with each other, or whether there is some common ground to be found.

What I do know, however, is that as our brains try to predict our behavior and keep us balanced, it is helpful for us to have coping strategies ready to use when needed. When someone cuts us off while driving to work, how can we respond in a way that we don’t “flip our lid” or become so stressed that we might cause an accident?

If a student or colleague says or does something upsetting, how can we maintain control of our response and avoid damaging the relationship?

When in Doubt, Reread and Look for More

This book set me on a new quest: to learn more about how the brain works and how we respond to stress. You can read an excerpt from the book that includes part of Barrett’s discussion of the one brain vs. triune brain. Now, I’m headed to a search engine to read more about the triune brain and the latest research related to it.

LATER, After a Long Weekend of Reflection

I began writing this blog on a Friday after thinking about the concepts included in the book for a couple of days. Now, some days later, I continue to ponder about what I’ve learned.

And, here’s where I am right now: I accept the new science showing there is no triune brain. And, finally, I’ve realized this new reality really isn’t as contrary to my way of thinking about how the brain works as I first thought.

Regardless of how the brain develops, it still produces powerful hormones like cortisol, which can trigger the “fight-flight-freeze” emotion, and dopamine, which is actually a neurotransmitter (known as the “feel-good” transmitter), both of which cause us to react in different ways.

So, I’m going to hold on to the metaphor of the “upstairs and downstairs” brain as an example of how to avoid or mitigate emotional crises. I can use the image of the “upstairs brain” for the times that I am self-regulated, calm, and able to think. When I find myself in a stressful situation and cortisol is rushing through my body, I can picture the need to “remain upstairs” and resist marching “downstairs” toward a meltdown.

To remain “upstairs,” I can employ strategies like concentrating on my breathing, expressing a need to think about what’s going on before responding, or going on a short walk. I can continue to add strategies to my toolbox to help ensure that I remain calm and rational in the face of significant stress.

And, so can you!

I’m still reflecting on what I learned in the book and how it relates, especially to social-and-emotional learning, and I’ll revisit this puzzle multiple times before feeling that it is completely resolved.

So, I’m thankful I picked up this interesting and provocative book. If you’re intrigued, join me in this investigation!

Here are some resources:

► This article by Dr. Sarah McKay about “rethinking the reptilian brain” may be the most helpful.

► A Yale article discounting the triune brain: “A Theory Abandoned But Still Compelling.”

► From neuroscientist Daniel Toker: “You Don’t Have a Lizard Brain.”

► And finally, this recent short article by Dr. Barrett for the New York Times (11/23): “Your Brain Is Not for Thinking: In stressful times, this surprising lesson from neuroscience may help to lessen your anxieties.”

I came across this article while also searching for clarity as a result of the cognitive dissonance I am experiencing after reading this lesson in her book, too. Thank you for the thoughts and resources!

Thank you for your comments! Would love to learn more about your reaction to the book!

I was so pleased to find your article recently. I can identify with so much of what you write! I have had to deal with a lot of cognitive dissonance since discovering last summer that a) there’s no empirical evidence for polyvagal theory and that b) the idea of the triune brain, as traditionally presented, is just not an accurate representation of how our brains evolved or work.

A significant part of the difficulty for me has been struggling to know what can be retained or salvaged in some way. Also I have realised that a key part of my identity as an educator and as a parent was wrapped up in the understanding that I had about how the brain worked and about emotion coaching and attachment and trauma and so on. I am discovering that much of what is written and practised by psychotherapists is not necessarily supported by neuroscience. This is frustrating because I had thought the exact opposite was true.

Practitioners frequently reference the neurobiology of trauma, for example, and I am sure for many people, like myself, this scientific underpinning was what gave so much credence to those practices and ways of thinking about and approaching them. But many of those ideas and practices also resonated on a very intuitive level – and, what’s more, they worked. They worked for parents and they worked for those of us supporting young people who have experienced relational trauma and ACEs. Even as I write this, I am conscious that even the use of those terms is probably also more controversial than I had ever realised.

A key part of processing the discomfort is in learning to try to accept that no single scientist has The Answers. All this debate serves to remind us how much there is that we don’t yet know and may never fully know. It’s likely that there is truth to be found in the work of many of the voices in the arena.

Perhaps the lessons are that we all need to be careful about presenting anything as the full picture about the brain and approach things with some humility. It’s hard to use the language of uncertainty when so much of what you have spent your working life doing is trying to encourage colleagues to accept the validity of a “brain based” or a “trauma-informed” approach because you know that doing so has very real positive outcomes for young people.

I’d dearly love to hear some of these people in conversation. What does Lisa Feldmann Barrett make of Dan Siegel’s work and vice versa? Robert Sapolsky wrote an endorsement of Barrett’s How Emotions Are Made, which was published the same year as his own Behave: The Biology of Humans at Our Best and Worst – in which he outlines which parts of the triune brain theory are problematic while also making use of it in other ways, and in which he devotes a chapter to discussing the role of the prefrontal cortex, including case studies in the changes in character/ behaviour of people who suffered damage to it. How does his understanding of the brain dovetail with Barrett’s? Is there actually a significant amount of common ground?

Finally, I find all of this so interesting as an insight into our human need for certainty and objective truth. I seem to be particularly prone to this, perhaps as a consequence of my religious upbringing. I am still learning to be comfortable with grey and to find a way to preserve confidence in my parenting, educating and self-therapy approaches and methods in the face of it.

Thank you for your thoughtful response. I found myself nodding as I read your reflections. And, your point that: “Perhaps the lessons are that we all need to be careful about presenting anything as the full picture about the brain and approach things with some humility,” is so wise. Thank you.