Does this quotation ring true for you?

Does this quotation ring true for you?

“The difference between mediocrity and excellence is our ability to engage in rigorous self-reflection about the task at hand; so, in order to improve our educational outcomes, we must focus on building the reflective capacity of our teachers” (p. 1).

In other words, teachers need to think their way into excellence by intentionally making regular reflection a priority in their practice. So say education consultants and authors Pete Hall and Alisa Simeral in their recent book, Creating a Culture of Reflective Practice: Capacity-Building for Schoolwide Success (ASCD, 2017).

Hall and Simeral worked together for several years in the same school where Hall served as principal and Simeral as instructional coach. Their books capture their collective expertise and wisdom, and I often turn to them for resources and ideas.

Reflection Cycle

This book builds on two of their previous books, Teach, Reflect, Learn: Building Your Capacity for Success in the Classroom (ASCD, 2015) and Building Teachers’ Capacity for Success (ASCD, 2008). It might be helpful to also refer to my 2015 review of Teach, Reflect, Learn.

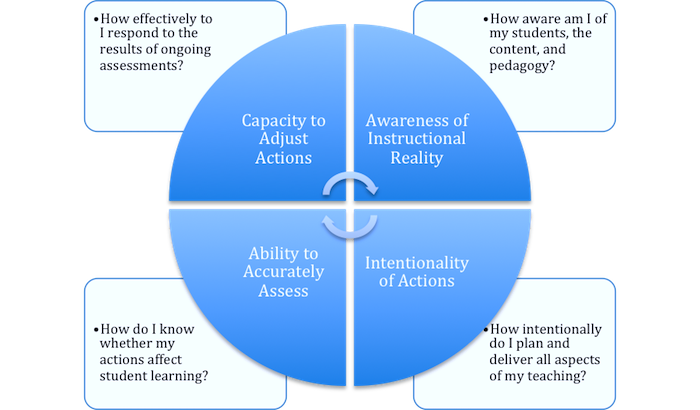

Readers of these earlier Hall/Simeral books will recognize their reflection cycle.

This four-part reflective cycle first helps teachers think about their current practice (students, content, and pedagogy). Next, it encourages them to intentionally plan to take action based on their students’ needs. The third part of the cycle encourages teachers to examine the impact of their teaching on their students’ learning. And finally, the fourth cycle is the “so what” part: How do I respond and act on my students’ learning (or lack thereof)?

After the authors introduce this cycle, they offer several different definitions of reflection and land on one that is easy to remember and quite simple: “Want to know what self-reflection really is? Think about it” (p. 24).

As cognitive scientist David Perkins reminds us: If you don’t think, you don’t learn. It is the ongoing reflection by a teacher about their practice that results in improvement. Teachers who don’t regularly reflect risk stagnation and thus miss opportunities to engage and teach their students at higher levels.

To illustrate the important characteristics of self-reflection, the authors turn to the thinking of many education researchers and thought leaders, including Dewey, Medina, Dweck, Costa, and Marzano. Characteristics mentioned include: metacognition, critical thinking, a growth mindset, greater awareness of their personal strengths and weaknesses, more effective integration of new knowledge, greater openness, and collaborative (pp. 28-29).

To illustrate the important characteristics of self-reflection, the authors turn to the thinking of many education researchers and thought leaders, including Dewey, Medina, Dweck, Costa, and Marzano. Characteristics mentioned include: metacognition, critical thinking, a growth mindset, greater awareness of their personal strengths and weaknesses, more effective integration of new knowledge, greater openness, and collaborative (pp. 28-29).

A big portion of the book is centered around Hall and Simeral’s Continuum of Self-Reflection, which identifies the four stages of teaching, beginning with the Unaware Stage and moving to the Refinement Stage, with two other stages in-between. Their “Continuum,” similar to a rubric, provides administrators and instructional coaches with insights and suggestions about how to work with teachers in each of the four stages and ways to advance their reflective practice.

Getting Started

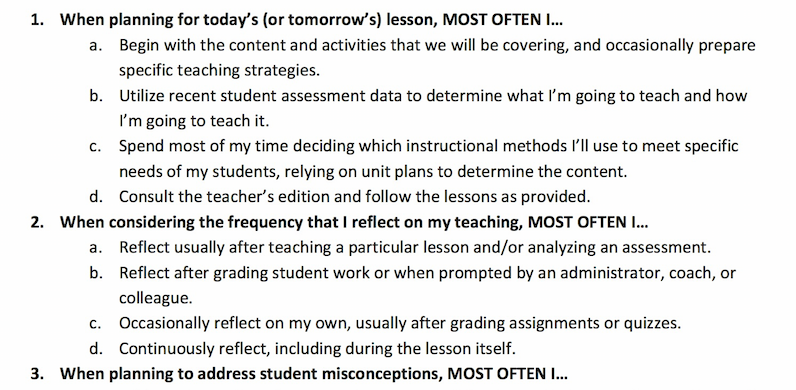

Interested administrators and instructional coaches who want to tailor their support to each teacher can ask their faculty to take self-assessment that will help place them in one of these four stages. Hall and Simeral offered this useful tool in their 2015 book, Teach, Reflect, Learn.

As the authors note in one of their earlier books, Building Teachers’ Capacity for Success, (ASCD, 2008), not every teacher will completely fit into one stage. Individual teachers can fall into several, depending on what they are teaching or when they accept a new teaching assignment. Hall and Simeral encourage administrators and coaches to view the Continuum not as an instrument for judgments but as a “tool to help school leaders understand a teacher’s current state of mind and identify the approaches that will encourage deeper reflective habits” (p. 40).

The revised Continuum in the new book (Creating a Culture of Reflective Practice) provides a capacity-building goal for each of the four stages. Additionally, for each stage, the authors provide examples of three different composite “teachers” to help the reader better understand the characteristics of teachers at that stage and the opportunities for seeding reflection and improvement.

The Continuum also provides information about the following (pp. 36-39):

- Teachers’ reflective tendencies

- Leadership roles (for the administrator and instructional coach)

- Strategic PLU and teacher-leadership support

- Transformational feedback (directives or prompts)

- Differentiated coaching strategies.

The Four Stages

Teachers in the Unaware Stage are generally new to the profession or have not yet become reflective thinkers. They rely more on rules and procedures and “getting the job done.” For those teachers, the capacity-building goal is to “build deeper awareness of students, content, and pedagogy.” For these teachers, the support is more directive and involves activities such as whisper-coaching when visiting a colleague’s classroom, short-term goal-setting, and writing lesson plans together.

Teachers in the Conscious Stage may be the most challenging—at least that seems to be the case to me! These teachers know that they could do better, but are satisfied with their current practice. As a result, the “Knowing-Doing Gap” is on display with teachers in this stage. For Conscious State teachers, the capacity-building goal is “to work with greater intentionality in addressing students needs, content, and pedagogical practices.” Support for teachers in this stage includes modeling a strategy or lesson; co-planning, co-teaching, and debriefing a lesson together; and meeting weekly for collaborative planning.

Teachers in the Conscious Stage may be the most challenging—at least that seems to be the case to me! These teachers know that they could do better, but are satisfied with their current practice. As a result, the “Knowing-Doing Gap” is on display with teachers in this stage. For Conscious State teachers, the capacity-building goal is “to work with greater intentionality in addressing students needs, content, and pedagogical practices.” Support for teachers in this stage includes modeling a strategy or lesson; co-planning, co-teaching, and debriefing a lesson together; and meeting weekly for collaborative planning.

A teacher in the third stage, the Action Stage, is committed to improving their practice and often asks for help when struggling. The capacity-building goal for these teachers is “to build on experiences and help strengthen expertise through- accurate assessment of instructional impact.” Support for Action Stage teachers includes: providing research from which to construct meaning, recording a lesson and discussing afterwards, and encouraging participation in a professional book club.

And, finally, teachers in the fourth stage, the Refinement Stage, are the teacher leaders. These teachers are reflective and use formative feedback to adjust instruction on the fly. The capacity-building goal for these teachers is “to encourage long-term growth and continued reflection through responsiveness to ongoing assessments.” Support for teachers in the Refinement Stage includes: analyzing data and student work samples, facilitating idea sharing through collegial conversations, and encouraging leadership small-group discussions around a common problem of practice.” Lesson study also comes to mind.

The Seven Fundamentals

The authors also embed what they consider to be seven fundamentals in the book and devote a chapter to the first four, and combine the last three in another chapter:

- Fundamental 1: Relationships, Roles, and Responsibilities

- Fundamental 2: Expectations and Communication

- Fundamental 3: Celebration and Calibration

- Fundamental 4: Goal Setting and Follow-Through

- Fundamentals 5, 6, and 7: Strategic Support, Feedback, and Coaching

This book is a treasure trove of advice, suggestions, and ideas for administrators, instructional coaches and any one else in the role of mentoring and supporting teachers. The seasoned experience of the two authors shines through. This can be a “go-to” book that one can turn to when focused on continuous improvement and deepening teachers’ reflective practice. You’ll find some inspiration, I’m sure.

Tolstoy’s Voice Helps Conclude the Book

Near the conclusion of the book the authors call upon Leo Tolstoy, the revered Russian author who also had an interest in education.

“The best teacher will be he [or she] who has, at his tongue’s end, the explanation of what it is that is bothering the pupil. These explanations give the teacher the knowledge of the greatest possible number of methods, the ability of inventing new methods and, above all, not a blind adherence to one method but the conviction that all methods are one-sided, and that the best method would be the one which would answer best to all the possible difficulties incurred by the pupil. That is not a method, but an art and a talent.” (Quoted in Schön, 1987)

“The best teacher will be he [or she] who has, at his tongue’s end, the explanation of what it is that is bothering the pupil. These explanations give the teacher the knowledge of the greatest possible number of methods, the ability of inventing new methods and, above all, not a blind adherence to one method but the conviction that all methods are one-sided, and that the best method would be the one which would answer best to all the possible difficulties incurred by the pupil. That is not a method, but an art and a talent.” (Quoted in Schön, 1987)

Isn’t Tolstoy’s description what we want in a teacher for every child? We know, of course, that it isn’t all “art and talent” – not something you are simply born with. Predispositions matter but well-supported teachers reach excellence through experience, reflection and determination.

Hall and Simeral think that we’ll get closer to that goal with mentoring, coaching, and targeted support to deepen each teacher’s ability to “think their way into improving.”

0 Comments on "Helping Teachers at Every Stage Build Their Capacity to Reflect"