By Bryan Rebar

By Bryan Rebar

Instructional Partner

Florence Middle School

Last spring, sitting in the library with the principal and assistant principal, posters covering the walls, the question that begged to be asked was “Where do we go from here?” We’d hosted educators from across the state, and we were eager to see what they’d found with regard to our self-identified problem of practice (PoP) which focused on differentiated instruction.

If you’re not familiar with the ABPC Instructional Round process, you can read more about it here. Basically, teams come from other schools on the same day. Each team visits three FMS classrooms, guided by our PoP. The succinct version of our PoP looked like this:

When you are in classrooms today, we would like for you to consider the following as we look for how our teachers are strategically maximizing student learning at every turn.

► In what ways can students tell you what they are learning and why it is important?

► What is the teacher doing to support the individual and group learning needs of her/his students?

► What evidence can you gather that shows different instructional strategies and tasks in place to meet the specific needs of students? (Such as evidence of different learning tasks in the room or evidence of classroom structures or supports that allow students to engage with the content in different ways)

(See FMS’s complete PoP handout here)

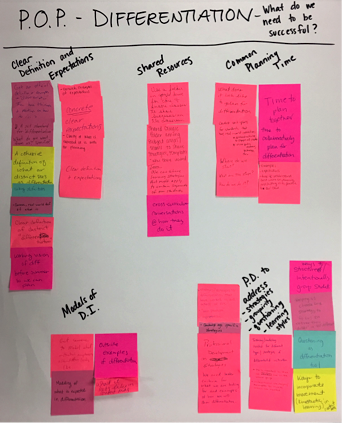

Now the day was done. The planning and preparation for our experience hosting an Instructional Round had come to fruition. Before us lay posters with post-it notes and posters with quadrants, full of data about our school and our pursuit of differentiated instruction.

Our school leadership team at Florence Middle School in Florence, Alabama holds the belief that teachers are the changemakers. So the first question, clearly, was: How can we get this data from the IR experience into the hands of our teachers so that we can continue to collectively grow our professional practices?

As we sat and discussed what to do, we knew that getting timely feedback was key to planning for future professional development. It was decided that the quadrant posters developed by the visiting teams would be shared with FMS teachers at the next faculty meeting along with a graphic organizer to help capture teacher voice.

The quadrant posters

I’ve joined up with ABPC’s Cathy Gassenheimer to put together this “skinny” on the quadrant posters, because these posters are really the essence of the feedback you get from the visiting teams.

After school teams have visited three classrooms each, they create an affinity map based on evidence gathered, focused on the school’s problem of practice.

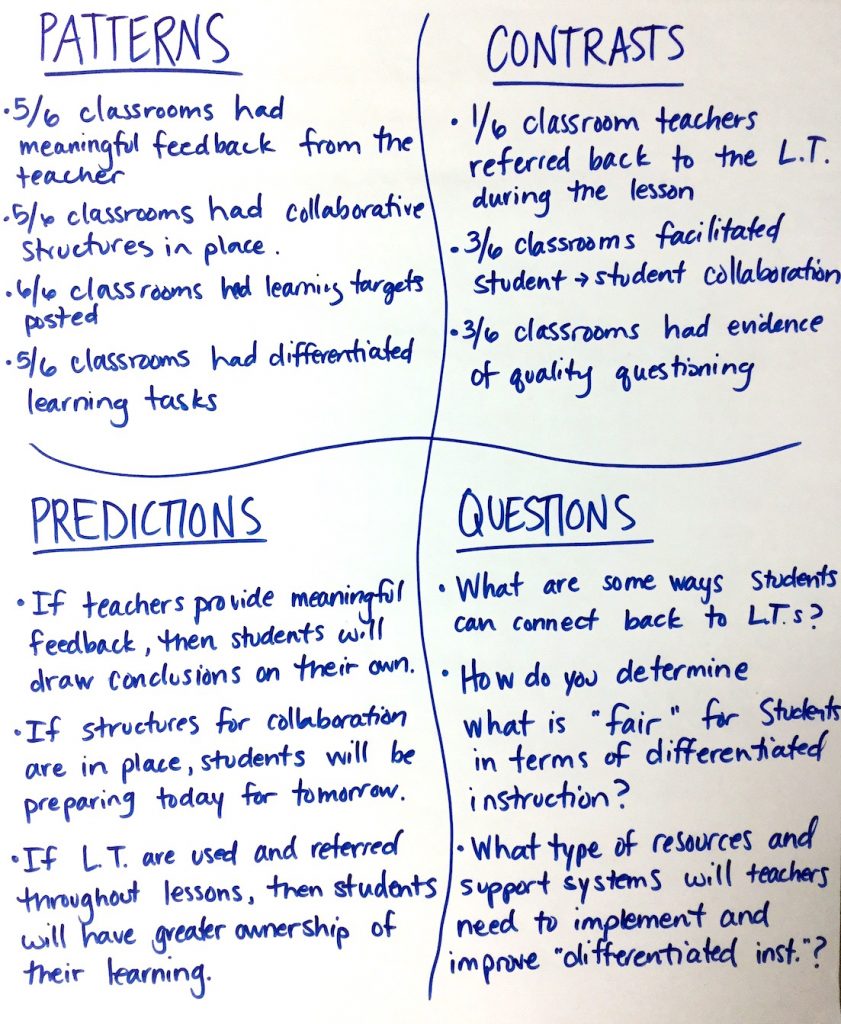

When the affinity maps are completed (each team places similar types of evidence together and identifies categories), teams are merged. Ideally, if there is an even number of teams, two teams work together using a Four-Quadrant Template:

- The upper left-hand quadrant identifies patterns. Participants look for evidence that was identified more than half of the classrooms (since teams have merged into pairs, they are looking across six classrooms, so “In 4/6 classrooms…”)

- The upper right-hand quadrant identifies contrasts, or outliers. For example, there may have been a classroom where students were identifying their own learning targets (“1/6 classrooms….”)

- The bottom left-hand quadrant is devoted to predictions, using this prompt: “If I was a student at this school and did everything expected related to the PoP, I would be able to…(for example) …identify what I was expected to learn and ask for help, if needed.”)

- The bottom right-hand quadrant is devoted to questions, which is the opportunity for team members to offer questions that might lead to reflection and the development of next steps at the visited school. For example, if a PoP was related to student engagement, a reflection question might be: “In what ways can you assure that when students are in small groups they are working collaboratively and not independently?” or “In what ways can teachers monitor the work of small groups when they are leading a small group simultaneously?”

We hope that gives you the big idea. Here’s the final quadrant from the teams visiting FMS:

What we did next

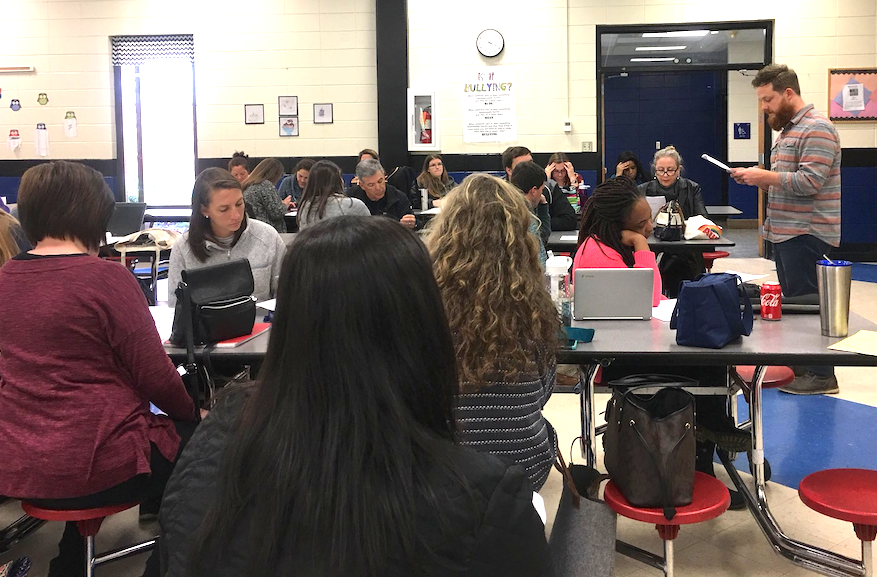

Following our Instructional Round, we gave teachers a few days to look over the data and complete their graphic organizers. We then took time from one of our weekly collaborative meetings to share out our personal reflections and dialogue about how we can improve in the area of differentiated instruction.

As a part of this process, teachers identified resources and other areas of assistance that they felt would help them improve their practice in this area of focus. Then, during each collaborative meeting, participating teachers shared out what support they felt would benefit them the most and recorded this information onto post-its.

An important part of this process was sharing the 4-Quadrant posters with teachers to help them reflect and draw their own conclusions about the content. Any questions that arose from the 4-quadrant posters, in particular the last one (shown above), were then used as discussion prompts in the collaborative meetings.

The post-its were gathered throughout the day as we went from meeting to meeting. Then our leadership team followed up by affinity mapping the teacher responses to look for trends.

What did we learn?

Teacher voice was consistent from collaborative team to collaborative team and several categories of needed support became apparent. We also learned through the experience of hosting an instructional round that our teachers like clear expectations and that they would like more focus on content-specific professional development.

Teachers want to work together with the district to develop a working definition of differentiated instruction and to set clear targets. Teachers want to see concrete examples of what this practice looks like in the middle grades. Teachers are eager to grow their practice and want to learn about content-specific strategies to use in their classrooms. They want a way to gather and build a collection of resources that are easily accessible by their collaborative team, curating an easy-access toolkit of best practices around differentiation.

What plans are unfolding?

The summer months were spent planning with school leadership teams, continuing to gather teacher voice, growing us forward in our instructional practices. First and foremost, school administration is committed to the concept that teachers need common planning time and will carry this into the future. This common planning time allows for our teachers to collaborate and find the best-practice strategies that can be used to differentiate student learning.

We truly have a faculty that is committed to reaching all learners by growing their professional practices. It is this time for collaboration that allows for teachers come together, engage in dialogue, and develop shared beliefs and goals. The collaborative planning time will also be used to identify individual student gaps and develop a toolkit of strategies that are aligned to meet the specific needs of students – including collaboratively created exemplar lessons and lesson-plan sharing.

Just as we advocate choice for our students, we will give teachers choice as we plan professional development opportunities. We want to be able to use some of our PD time to go visit other schools that are doing these practices well, so we can see them in action.

We have also made changes to our lesson plan format for the current year. This format now allows teachers to specifically identify the differentiation strategies they are implementing and allows for teachers to anticipate reteaching opportunities. It also allows teachers to develop essential questions at various levels of Webb’s Depth of Knowledge to help scaffold student learning. The lesson plan template also highlights cross-curricular and real-world connections to engage student interests.

We’re left with a choice

When presented with data from instructional rounds, you are left with a choice. You can either dismiss the information and continue on your current path, or you can take the time necessary to reflect, respond, and grow your practice. Getting the data from instructional rounds into the hands of teachers and taking the time to listen to their voices are enormously helpful in the effort to make lasting positive change. The momentum created by experiences like this has a real ripple effect – it drives and improves our instructional practices, ultimately impacting student achievement.

We are looking forward to going through another instructional round process soon to further identify areas of growth and areas of opportunity. At each IR opportunity, we’ll reevaluate and adjust our problem of practice to reflect the everchanging needs of our campus.

Why should you care about instructional rounds?

The greatest benefits to using instructional rounds as an educational leadership tool is that you have the freedom and choice to identify a problem of practice that is relevant to the greatest needs in your school. As an educational leader, the resulting data is meaningful and can be used to drive school improvement. The power of involving your school and teacher leaders in identifying the problem of practice and then analyzing the resulting data allows for shared accountability and builds collective efficacy.

Read a post about IR by ABPC consultant Pat Johnson:

“What I’m Learning from ABPC’s Instructional Rounds”

Bryan Rebar started his teaching career in Cincinnati, Ohio, teaching grades 4-7 (reading, math and science) in a school for students with Autism and other spectrum disorders. He also taught middle school science in Texas and in the Florence (AL) City Schools, where he is now the Instructional Partner at Florence Middle School. He holds a BS in Education and a Master’s in Middle Childhood Education with a focus on Reading, Mathematics, and Science.

Thank you, Bryan, for a very comprehensive look at Instructional Rounds as experienced by FMS. I particularly appreciate the follow-up that you planned — allowing teachers to make meaning of the data, plan next steps, and identify requisite support. Your leadership in planning and implementing this process was obviously critical to its success. p.s. I love the pictures!