What if…schools were recreated from the inside out?

What if…schools were recreated from the inside out?

What if…curiosity and motivation were the key drivers in improving teaching and learning for all?

And what if this idea was taken to scale?

This is the premise of a new book by Bryan Goodwin, president and CEO of McREL International and his colleagues. Unstuck: How Curiosity, Peer Coaching, and Teaming Can Change Your School, chronicles an improvement initiative in the State of Victoria in Australia (home to Melbourne), and speculates about whether this type of improvement could happen in the United States.

Goodwin, frustrated with the top-down, high-stakes testing environment that frustrates many teachers and students, was intrigued with the Australian State of Victoria’s process and results.

Goodwin, frustrated with the top-down, high-stakes testing environment that frustrates many teachers and students, was intrigued with the Australian State of Victoria’s process and results.

This improvement initiative was spurred by the work of David Hopkins, who previously served as the chief education advisor to former British Prime Minister Tony Blair. Hopkins followed Michael Barber, who had successfully managed a Literacy and Numeracy Initiative, later named “Deliverology,” in Britain that resulted in student scores improving by about ten points over three years.

But after that, there was a problem: the scores had plateaued. And, Blair wanted to know why. Hopkins explained that the plateau was to be expected, because the improvement strategy launched three years earlier, had remained static, and predictably resulted in declining results.

‘I would make no apology for what Michael [Barber] et al. did in 1997,’ Hopkins told Education Week. To so dramatically move the needle on such a large system ‘has to be a stunning achievement.’ But, he added, ‘and this is a big but, that was only the first stage in a long-term, large-scale reform. And one of the reasons why we’ve stalled is that more of the same will not work.’ (Olson, 2014), p. 2, Unstuck.

“Deliverology,” the British initiative, relied on a top-down model of improvement where schools employed literacy and numeracy programs developed by Barber and colleagues. Problems mounted as some schools implemented those programs inconsistently. Additionally, while teachers received professional learning through the initiative, the PD focus was on implementing the program exactly as designed and not about adaptation or the use of effective teaching strategies.

Hopkins, and later Goodwin, realized that to address the predictable performance plateau of reform initiatives, educators had to “let go” of the initial approaches when they no longer worked. In other words, they had to “adopt and then adapt” (p. 15).

Hopkins later had the opportunity to do exact that—adopt and adapt— when he accepted a temporary teaching position at the University of Melbourne. Fortuitously, for Victoria, Hopkins met Wayne Craig, the regional director of the Northern Metropolitan Region in Victoria, which served more than 75,000 students.

Victoria’s Fresh Approach

Both Craig and Hopkins felt a sense of urgency as they reviewed the current status of many schools in Victoria. Facing low student achievement and a financial crisis brought on by the declining population of some schools, it was clear that something needed to be done and done quickly.

What they decided was quite audacious: to close certain schools, thus causing the disruption of many students and teachers, while simultaneously launching a school improvement effort to transform teaching and learning.

To be successful Craig and Hopkins knew they needed a fresh approach: “one that could truly increase teachers’ professional capacity, inspiring and helping them to help one another develop better teaching practices that would aim to increase both student learning and motivation (p. 22).”

And – of first importance – rather than design a top-down improvement model they decided to start with teachers and students.

Tapping the expertise of the best teachers and researchers on motivation and curiosity, they went to work. Over time, as Bryan Goodwin and his colleagues report in Unstuck, they developed a six-pronged approach:

- Starting with a moral purpose

- Unleashing curiosity

- Building on bright spots

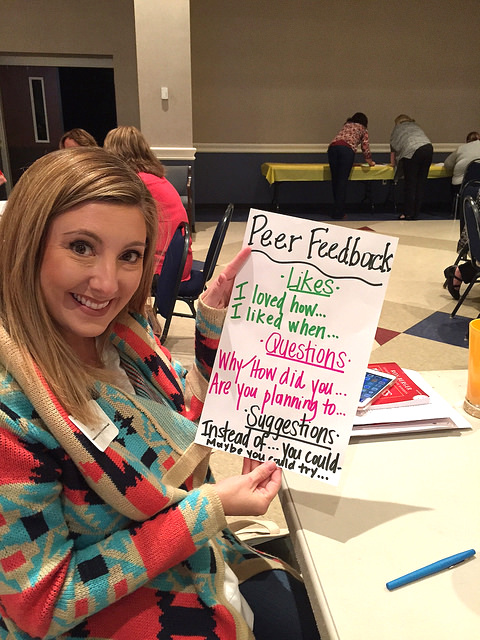

- Peer coaching toward precision

- Leading from the inside out

- Moving the goal posts

Most of the six approaches are fairly self-explanatory, and I’ve embedded links that explain the first two. Additionally, Goodwin points to “positive deviants” when he refers to bright spots – the outlier schools and classrooms that are beating the odds.

And, leading from the inside out means that school leaders, instead of issuing mandates, would ask empowering questions that helped turn what could be a “threat condition” into a “challenge condition,” thus “encouraging people to fail forward” (p. 41).

Assuring Forward Motion

The next step involved developing theories of action corresponding to the six-pronged approach. Four whole-school priorities were identified, including:

The next step involved developing theories of action corresponding to the six-pronged approach. Four whole-school priorities were identified, including:

(1) prioritizing high expectations and authentic relationships;

(2) Emphasizing inquiry-focused teaching;

(3) Adopting consistent teacher protocols; and

(4) Adopting consistent learning protocols.

Continuums were developed for these practices and are available in the appendix of the book.

A study guide on the book is available here.

What Might This Mean for Alabama?

As I read the book, I kept finding myself nodding in agreement. This inside-out approach, with an emphasis on inquiry and answering the question “how can we make it better?”, really makes sense. The process honors both teachers’ and students’ knowledge and desire to “own their learning.”

Adopting this approach would require a major sea change for most schools and districts. But, what might happen if we listened first to teachers and students? If curiosity and motivation (among adults and children) were the key drivers for improvement?

I think we’d see a renewed sense of purpose among educators and students and, as a result, learning would soar. Why do I think that? We see evidence of the power of this kind of model in Alabama’s own “bright spot” schools.

Cathy Gassenheimer is Executive Vice President for the Alabama Best Practices Center.

0 Comments on "What Can We Do When Our Improvement Strategies Get “Stuck”?"