Back in fourth grade I spent a lot of time thinking, “When I’m an adult in this school, I’m going to change [insert problem/solution here]”.

Back in fourth grade I spent a lot of time thinking, “When I’m an adult in this school, I’m going to change [insert problem/solution here]”.

I don’t know if my assumption that I would be an adult in the school came from not wanting to be a firefighter or a princess, or because I hadn’t yet developed the foresight to picture myself in any future outside of a school – or if it was the beginning of some latent desire to work in education. But I can say for sure that from an early age, I’ve been interested in what makes the best school environment for kids.

Perhaps it’s no surprise then that 18 years later I find myself working in education and consequently back in schools. On some of these days – easily my favorite days – I’m supporting ABPC’s inspiring Instructional Rounds program.

Earlier this month I was able to observe an instructional round at three-year old Pike Road Elementary in Montgomery County, and I was absolutely blown away by what I saw.

Learners Everywhere

It is interesting to look at a school from this adult side. That student in me who thought about my elementary school and what I would like to see it become now realizes that there are adults who spend lots of their time thinking, dreaming, working, eating, and breathing “best school.”

Their vision might not include zip lines in lieu of stairs or chocolate milk everyday (I dreamed big when I was younger) but it does include taking care of chickens in the hallway, learning how to build robots that will do your recycling for you, creating video games from scratch, and so much more.

While these Pike Road features that I’ve listed here are very tangibly cool, what is even cooler is what I saw that isn’t so easy to describe or measure. Everywhere, I witnessed a classroom culture that involves trust between teachers and their students, or what Pike Road likes to call “Lead Learners and Learners.”

While these Pike Road features that I’ve listed here are very tangibly cool, what is even cooler is what I saw that isn’t so easy to describe or measure. Everywhere, I witnessed a classroom culture that involves trust between teachers and their students, or what Pike Road likes to call “Lead Learners and Learners.”

I saw a confidence in every kid’s abilities – from both the adults and the kids themselves – and a shared excitement about learning that was beginning to translate into students tracking their own progress and so becoming “leaders of their own learning.”

My Pike Road visit makes the 3rd instructional round I’ve had the opportunity to attend. Each one has been an amazing and inspiring event. I must admit that I’m especially proud of Pike Road because it’s in my backyard. I went to school not far from here. I couldn’t help but think back to my own experience and wonder if there were people like this then, thinking and working so hard to make my life and my future better. I like to imagine there absolutely were, but I am still jealous of these kids today.

Instructional Rounds: The Basics

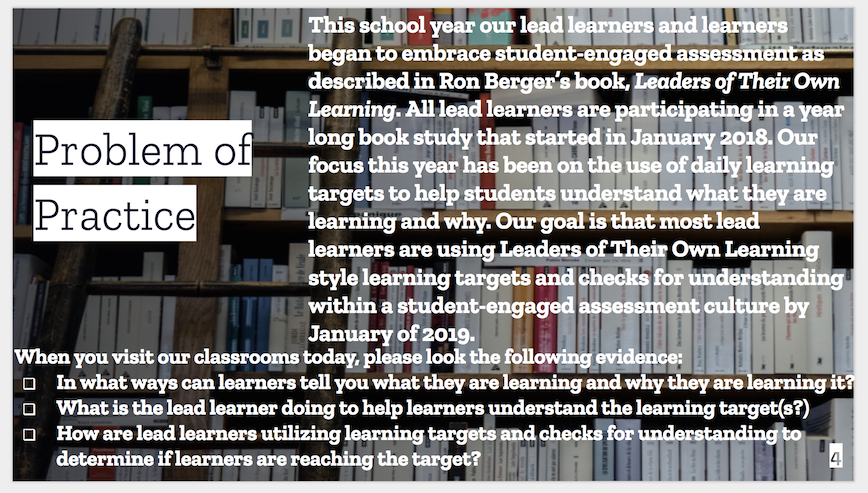

I had never heard of an instructional round before I came to the Best Practices Center. If you’re not that familiar with the process, be sure to read this post by Cathy Gassenheimer. It’s a very clear explanation that helps you understand how Instructional Rounds benefit both the educators visiting the school and (most of all) the educators IN the school who learn from visitor questions and feedback. Each instructional round is anchored by a Problem of Practice, written by the school being visited. At Pike Road Elementary, this was the PoP:

Once all our visiting educators were in agreement on how to look for fine-grained evidence related to the Pike Road PoP, we got to go into the classrooms (the best part!).

In the first classroom I visited students were working on using toy cars, cinder blocks and wooden tracks to create ramps, to learn how mass and energy interact. Grouped all around the room, learners were working together to build the best track – one that would get their toy car the farthest, the fastest.

What might have looked like chaos from the outside – with kids moving around, going into the hallways, cars flying everywhere, and frequent exclamations of frustration or celebration – was actually very engaged learning when you looked at answering questions based on the PoP, using fine-grained evidence.

The Lead Learner (teacher) was able to skillfully bring them back into focus, help them reroute their thinking when needed, and support them to realize what mistakes they might be making and what the learning associated with their task really meant.

Here are some examples of the notes I took while observing this classroom:

Learners are encouraging each other to build tracks that are related to the task. Observing one group, I hear things like “this part has to be flat. Heavier cars go faster, so we need to think about that.”

In another group “Guys, I have a great idea. Do you recognize this from the video we watched?” while holding a new piece of equipment from the supplies the Lead Learner provides at the front of the room. Her instructions had been for the learners to use whatever supplies they felt were needed to get their toy car to go the furthest the fastest.

Several times the Lead Learner brings the whole group to her attention, saying, “Everyone give me your eyes really quickly. I’ve had several people ask me the same question, so I am going to clarify for everyone.” And “What do we do when we fail? Do we do the same thing again? No. Try something different.” And “Do you need to reference the video we watched earlier?” “What is your learning target today?” “I haven’t seen anyone measure yet.”

Once some teams start testing their ramps the room begins to ring out with phrases like “We need to have a level angle. That was 4 feet. How many feet is 60 inches? We need a ruler, go get a ruler!”

Amid all the moving parts of the classroom, the lead learner navigates her way through small groups answering questions, which prompts more of her own questions, giving instruction when needed.

She is saying things like “This is 48 inches. Are speed and energy related?” and “Video it, measure it, prove it.” and “Your group has gone a whole 5 feet already, go out into the hallway to see if you can go even farther.”

Like that, our 15 minutes were up, and we had to leave the classroom just as most of the student groups were really beginning to master their task.

Good Behavior Grows Out of Trust

I started observing the next classroom before I even got into it. A small group of first graders in the hallway were working on a “breakout box”. They were using math to solve problems that led to clues to eventually open the box.

When I walked inside the classroom I saw kids grouped together learning how to tell time using a hula hoop with numbers spread around the inside to mimic a traditional clock face, and the Lead Learner working with a larger group of learners in a circle going over the arms of the clock.

As I was asking the learners what they were doing with the hula hoop clock, the breakout box group rushed in to find their latest clue and back out into the hallway to discover the next one.

Talk about trust. Their controlled excitement about learning was in direct contradiction to a comment I have heard so many times: “My kids would never behave like that – I couldn’t trust them to turn them loose while I was working with another group.” Or “My kids couldn’t manage themselves well enough to be able to do an activity on their own without me telling them what to do.”

Not only was every young learner that I asked able to tell me what their daily learning target was (“I can tell time down to 5 minutes”), most of them were able to tell me how they know they are doing poorly or whether they are mastering the subject. “We can tell we are getting it when the work starts getting too easy. Once we do that, we can flip this sheet over and follow the harder instructions until that’s easy too.”

Both of these things were said to me by the kids in the hula hoop small groups. The lead learner was still working with her other group that was on a different level of understanding.

These Learners Expect to Make Mistakes

In both of these classrooms I saw an ease and trust between the learners and the lead learners. Students were comfortable in their environment making mistakes to get to their ultimate goal. The lead learners trusted the learners to work independently and stay on task in small groups.

In both of these classrooms I saw an ease and trust between the learners and the lead learners. Students were comfortable in their environment making mistakes to get to their ultimate goal. The lead learners trusted the learners to work independently and stay on task in small groups.

The learners also held each other accountable. In the first classroom, one learner said to another one, “Where are you getting those numbers? How do you know that?” in response to a proposed ramp configuration. I also heard the group of kids trying to solve the breakout box saying things to each other like “You should finish that problem, but I don’t think it’s right for this clue. We all have to get the same answer.” And “Okay. Let’s help each other really quick.”

Because of this culture, learners can begin to feel confident about tracking their own progress and ultimately leading their own learning.

Spending Time with Some Project Winners

Even though we only got 15 minutes in each classroom, after lunch, we got a real treat and some C6 Makerspace Learners showed us some of their winning technology projects.

These ranged from a Recycling Robot and a Virtual Table Tennis game to a stop motion video created with an iPad and a giant piano keyboard you play with your feet. It reminded me of the famous scene from the Tom Hanks movie, Big, except these girls weren’t trapped in an adult body and they built the piano from scratch.

These ranged from a Recycling Robot and a Virtual Table Tennis game to a stop motion video created with an iPad and a giant piano keyboard you play with your feet. It reminded me of the famous scene from the Tom Hanks movie, Big, except these girls weren’t trapped in an adult body and they built the piano from scratch.

All of these project winners were able to explain how they created these things, how they worked together, what they learned from working together, and how this applies to their future. I asked the stop-motion directors how they were assigned this task and they told me that the 3 of them were finished before the other learners and the teacher asked them to work together to make a video. They took the lead from there.

I am inspired by these elementary aged kids. I understand what I saw was a short snippet of a much larger picture, but it was a hopeful picture – a glimpse of what might be possible in a school culture of collaboration, respect and innovation.

What We Took Away

We spent the rest of the day truly assessing the information we’d gathered from our short time spent in those classrooms and making meaning of that.

One core principle of Instructional Rounds is that they are not judgmental. One of our visiting IR participants made a good point in trying to explain what it’s like to gather evidence without being judgmental. He said it’s a lot easier to be judgmental – you just say you don’t like what you saw.

Picking out fine-grained evidence is harder. One observer might see chaos, with cars and kids flying around everywhere. Another might see all the learning taking place, as kids work together to make meaning of their daily learning target through real world application. The truth of the situation reveals itself when you are forced to examine and record only what you see happening and not what you perceive happening.

What was most satisfying was to understand that while each of us was only in each classroom for 15 minutes at a time and visited a number of different classrooms, once we came together to share our findings, as a group we found more similarities than differences and were able to come to similar conclusions.

Throughout the afternoon our visiting participants grouped the different pieces of evidence together using “affinity mapping.” This is done in several steps and processes, first non-verbally by similar category, then verbally by giving each grouping of evidence a name. This is actually a lot harder and a lot more work than I am making it sound like it is.

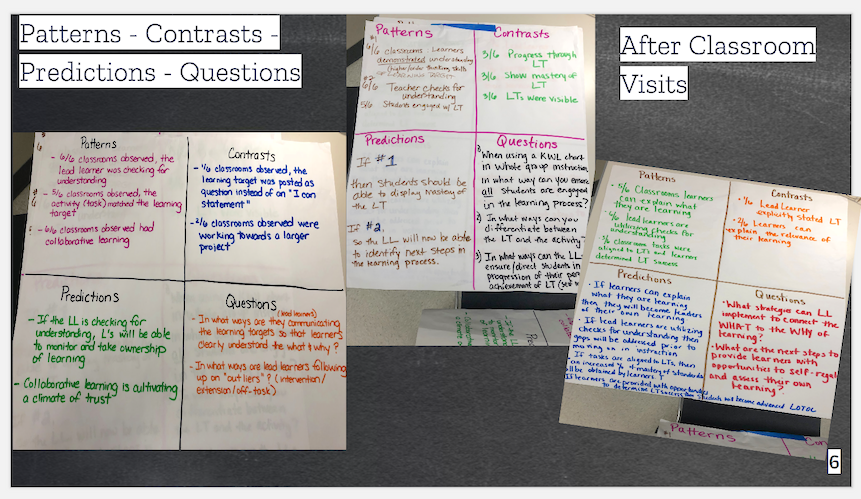

After that, two teams are merged into one and they can compare each other’s affinity maps and ask questions. Through several other exercises, the teams are asked to make patterns, contrasts, predictions and questions based off of the pieces of evidence found on the affinity maps (for example, in 6 of 6 classrooms observed the lead learner was checking for understanding).

It was especially rewarding to leave the products of our work with the school because it makes the data worthwhile. The administrators and learners are able to take the data these participants have given them about what they saw in their classrooms and make their own predictions and questions on how to move forward.

My big takeaways? Great educational experiences don’t just happen by accident. And getting kids to learn with ease isn’t easy. The staff in that building truly cares what the kids are learning and how. They care about the culture, they care about the kids themselves, they care about the content, and they care about each other. The looks on the learner’s faces when they can proudly show you what they’ve mastered represents a lot of work by the lead learners. Perhaps more work than the learner realizes.

Emily Strickland is Program Coordinator for the Alabama Best Practices Center. A native of Montgomery, she attended Saint James School from kindergarten through graduation and still talks to her best friends from primary school every day. In 2012, she earned a bachelor’s degree in English from Auburn University and worked for several nonprofits before joining ABPC in 2017. Reach her via email at [email protected].

0 Comments on "Student-Led Learning in a Culture of Trust: Our Instructional Round at Pike Road Elementary"