Walking into a first grade classroom, I noticed the teacher working at a table with six students. The other students were working independently across the room. Some had iPads, one was using a SMART Board, and others were completing a worksheet.

I approached the student at the SMART Board and asked about her learning target, or “I Can” statement(s). She pointed to an adjacent board and summarized the two learning targets: “I can read words with ‘ou’ and ‘ow’ sounds” and “I can write words with ‘ou’ and ‘ow’ sounds.” She pointed me to the SMART Board and showed me the words she had created thus far: “clown, frown, cloud, sound…”

She seemed very self-sufficient and goal-oriented. So I wondered aloud what she might do if she got stuck or confused. She looked at me, paused briefly and replied, “Well, I’d have to come up with a creative solution!”

Talking to students about their learning is both rejuvenating and encouraging. And that’s one of the main reasons I love facilitating instructional rounds across the State of Alabama.

The ABPC Instructional Rounds program

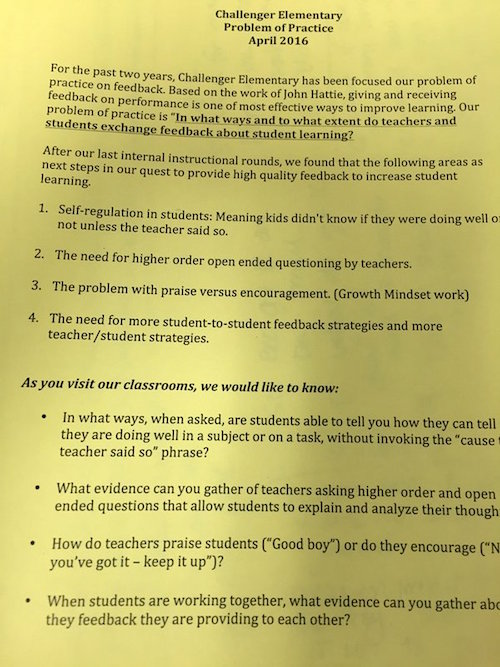

Instructional Rounds is a process developed by Richard Elmore and colleagues at the Harvard Graduate School of Education to help schools and districts develop a common vision of effective teaching and learning. This common vision then helps educators identify an area of focus – called “problems of practice” – and gather evidence to help a school and/or district identify next steps.

According to Elmore, “Classroom observation in the network rounds model is a discipline – a practice in the senses that it is a pattern of ways of observing and talking and is designed to create a common understanding among a group of practitioners about the nature of their work” (Instructional Rounds in Education, p. 85).

Accordingly, Elmore and colleagues recommend that the same group of educators participate in a series of instructional rounds to develop this common vision.

The instructional rounds we sponsor are a “variation on the theme.” We invite members of our networks to select from among 18 or so instructional rounds events held at elementary, middle, and high schools. As a result, at any given round, the group will be unique and won’t reconvene again to work on that common vision.

We started conducting our variation of instructional rounds about six years ago for several reasons. First, while it isn’t an extended process, it does provides the opportunity for educators to spend a day with colleagues across the state dialoguing about instructional practice – something that doesn’t often occur.

Second, it offers educators the opportunity to practice “descriptive observation,” in which participants are expected to record exactly what they see and hear in as precise a manner as possible. By doing so, participants experience a “laser-like emphasis on the cause-and-effect relationship” between what the teachers and students are doing and “what students actually know and consequently do” (Instructional Rounds in Education, p. 89).

The third reason we host instructional rounds is to showcase schools that have identified a discreet problem of practice as a priority and are beginning to pursue solutions.

We tell participants that – if we do our job correctly – their “head will hurt” at the end of the day. The type of concentration and deep level of conversation that an instructional round requires is invigorating, but also exhausting (in a very satisfying way).

This year’s focus: Student-engaged assessment

Problems of practice featured during this most recent series of rounds largely concentrate on student-engaged assessment (SEA), the focus of the Powerful Conversations Network. Inspired by Ron Berger and colleagues at Expeditionary Learning (now called “EL Education“), student-engaged assessment gradually shifts the responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student.

Problems of practice featured during this most recent series of rounds largely concentrate on student-engaged assessment (SEA), the focus of the Powerful Conversations Network. Inspired by Ron Berger and colleagues at Expeditionary Learning (now called “EL Education“), student-engaged assessment gradually shifts the responsibility for learning from the teacher to the student.

(Pictured right: Principal Clifford Porter shares Columbia HS’s problem of practice.)

To be more specific, Berger defines student-engaged assessment as a process that “changes the primary role of assessment from evaluating and ranking students to motivating them to learn. It builds the independence, critical thinking skills, perseverance, and self-reflective understanding students need for college and career…” (Leaders of Their Own Learning, p. 5)

Among the schools we visited this spring, some problems of practice focused on the SEA strategy of student-friendly learning targets. Others focused on student engagement, while still others were geared toward students self-assessing their learning and/or teachers embedding checks for understanding and providing targeted feedback throughout the lesson.

In one sixth grade math classroom, the student friendly learning target was “I can graph linear equations using the slope and y-intercept.” Students were working in small groups responding to specific questions posed by the teacher. The teacher was walking from group to group listening to the discussion and coaching students when needed.

Because instructional rounds encourage participants to focus less on teacher actions and more on what the students are doing, I began to notice some interesting data:

In some small groups, all four students were actively engaged in the learning process – reading and discussing the problem, rolling the dice (which represented the slope and y-intercept), and having academic conversations about what they were learning. In other groups, one or two of the students were doing most of the work, while the others watched and occasionally took notes.

Classroom visits to gather evidence

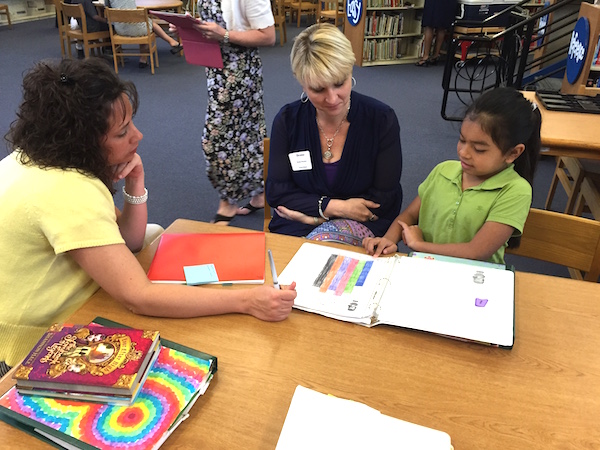

Most of our instructional rounds had between 18-30 participants who, in teams, visit three classrooms for 15 minutes each. They work diligently to gather fine-grained evidence aligned with the school’s focus (e.g., a problem of practice). To help them prepare, we offered examples and non-examples of the type of evidence we were hoping they would gather.

For example in a school whose problem of practice related to student engagement, the following evidence was gathered:

Non-example: Students engaged in a reading activity.

Better, but still could be more precise (e.g. what is the assignment? What word is highlighted?): Student reads, picks up highlighter, and highlights a word while reading.

Even Better: Students reading aloud.

• S1: “What does this word mean?”

• S2: “I don’t know. Let’s look it up!”

Individual and team evidence and dialogue

Upon completion of the classroom visits, participants individually review the evidence they gathered and select three to four evidence strands for each classroom visited.

Table teams then dialogue about the evidence gathered, with one person serving as an “evidence police-person” to ensure that the evidence is: (1) related to the school’s problem of practice; (2) non-judgmental; and (3) as fine-grained or precise as possible.

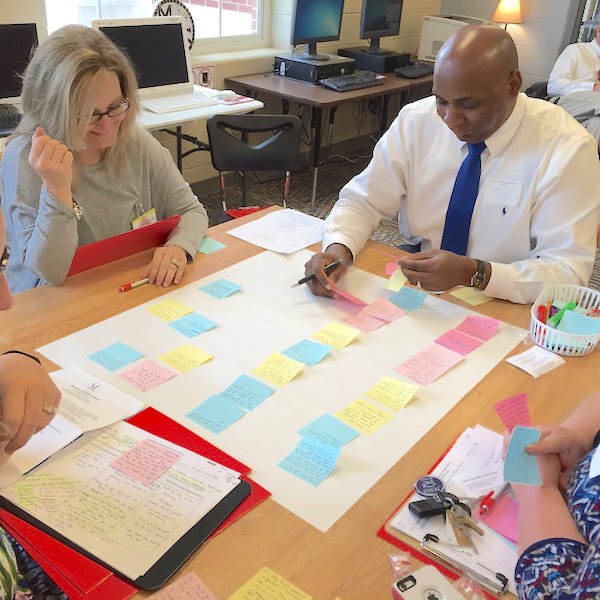

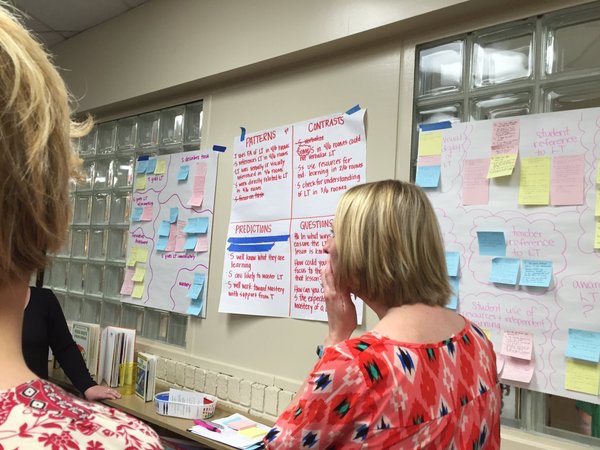

Table teams then use evidence – which they transfer to post-it notes of different colors (colors assigned to different classrooms) – to create an affinity map. Similar evidence is grouped together and the groupings are titled.

Looking for patterns

Teams are then merged so each individual is now looking at evidence from six classrooms – the three he/she visited along with the three visited by the other team. Once again, teams look at evidence for the three criteria listed above.

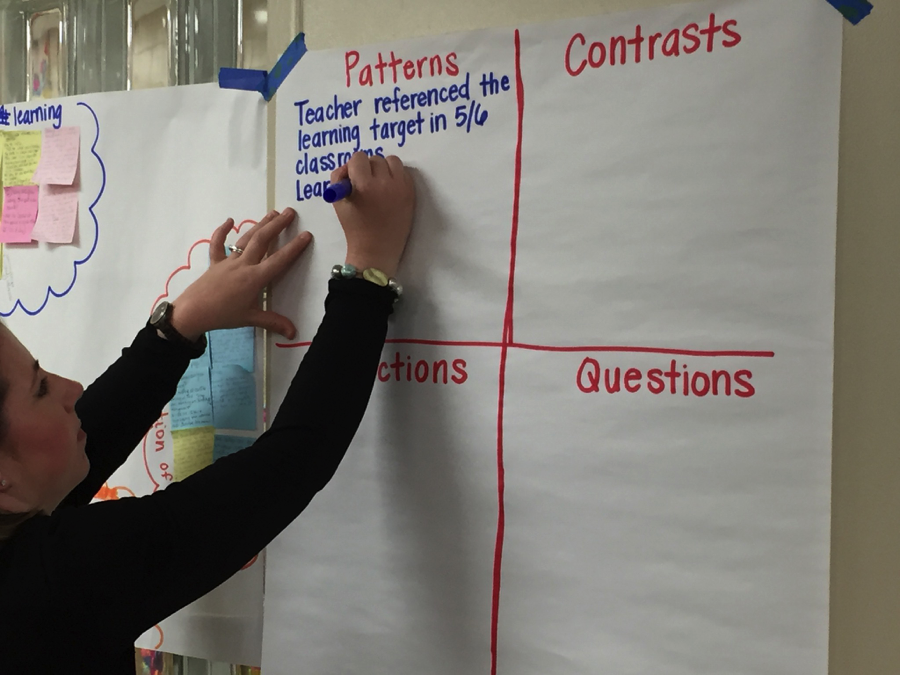

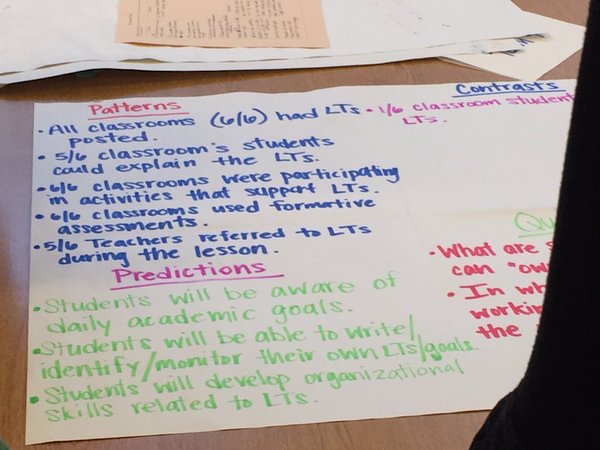

When satisfied with the evidence and the groupings, the combined team begins to look for patterns and contrasts. Patterns emerge when evidence is seen across more than a majority of classrooms. And, the pattern is stated in a way to show the number of classrooms in which the pattern was seen. As an example, one combined team surfaced this pattern: Teachers referenced the learning target in 5 of 6 classrooms.

Teams then look for contrasts, which are outliers. Contrasts occur when evidence is apparent in fewer than a majority of classrooms. In the case of one instructional round, the team found that in one of six classrooms, students were generating their own learning targets.

Making predictions

Teams then use the evidence gathered to make predictions about students at the visited school. They use the following prompt:

“If you were a student at this school and you did everything you were expected to do, what would you know and be able to do (in light of the patterns observed)?”

The previously identified patterns can help teams make these predictions. As an example, one team made the following predictions:

- Students will be aware of daily academic goals

- Students will be able to write/identify/monitor their own learning targets

- Students will develop organizational skills related to the learning targets

With practice, individuals can make these predictions more global. For example, Thomas Fowler-Finn, in his book Leading Instructional Rounds in Education, provides the following predictions as examples:

- Students will walk away with little ability to demonstrate their own thinking without teacher direction.

- Students will take responsibility for and initiate their own learning.

- Students will know that if they hesitate, someone else will do the work.

Surfacing “wonderings”

The final aspect of the team work gives individuals the opportunity to surface “wonderings” or questions they have about what they saw in the classroom. This part of instructional rounds is the closest that anyone comes to moving away from evidence-based discussion to making conjectures about what they saw and weighing possible changes in practice.

By the time the teams get to this part of the discussion, they have thoroughly discussed what they’ve seen. We remind them to look at the contrasts or “outliers” identified to prompt their wonderings. For example, a question that has emerged often during instructional rounds we’ve held over the years is related to small group work: In what ways can you ensure that students are working collaboratively rather than independently in small groups?

Pulling it all together: the Gallery Walk

To prepare for the final debriefing, participants visit the combined team charts to compare and contrast the identified patterns, contrasts, predictions, and wonderings. A person from each team stays behind to share insights and respond to questions.

The final debrief

Because participants at our rounds won’t meet together again and there won’t be a process that takes them to the “next level of work,” we designed a different debriefing process. It begins with a brief discussion of the patterns and questions that exist across all team charts during the gallery walk.

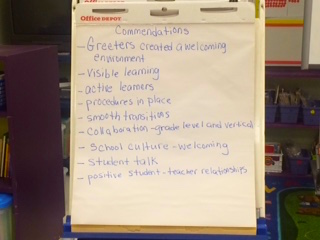

We then add a “commendations” discussion to the mix because we want to leave positive insights gleaned with the faculty who so willingly opened their doors to visitors. (Example at right from Creek View Elementary in Alabaster City.)

We then add a “commendations” discussion to the mix because we want to leave positive insights gleaned with the faculty who so willingly opened their doors to visitors. (Example at right from Creek View Elementary in Alabaster City.)

Finally, we end with a reflection in which participants discuss what they’ve learned personally. Quite often, we hear educators state that descriptive observation is more challenging than they thought. They often point to how difficult it is to put aside their “judgment hat” and just focus on the facts.

Other participants will note that they found they were spending much more time focusing on the students and the learning instead of on the teacher and the teaching, which is one of the major shifts promoted by instructional rounds.

Because of this shift, the process generally gives participants a better indication of whether or not learning is occurring. And, isn’t that what matters most?

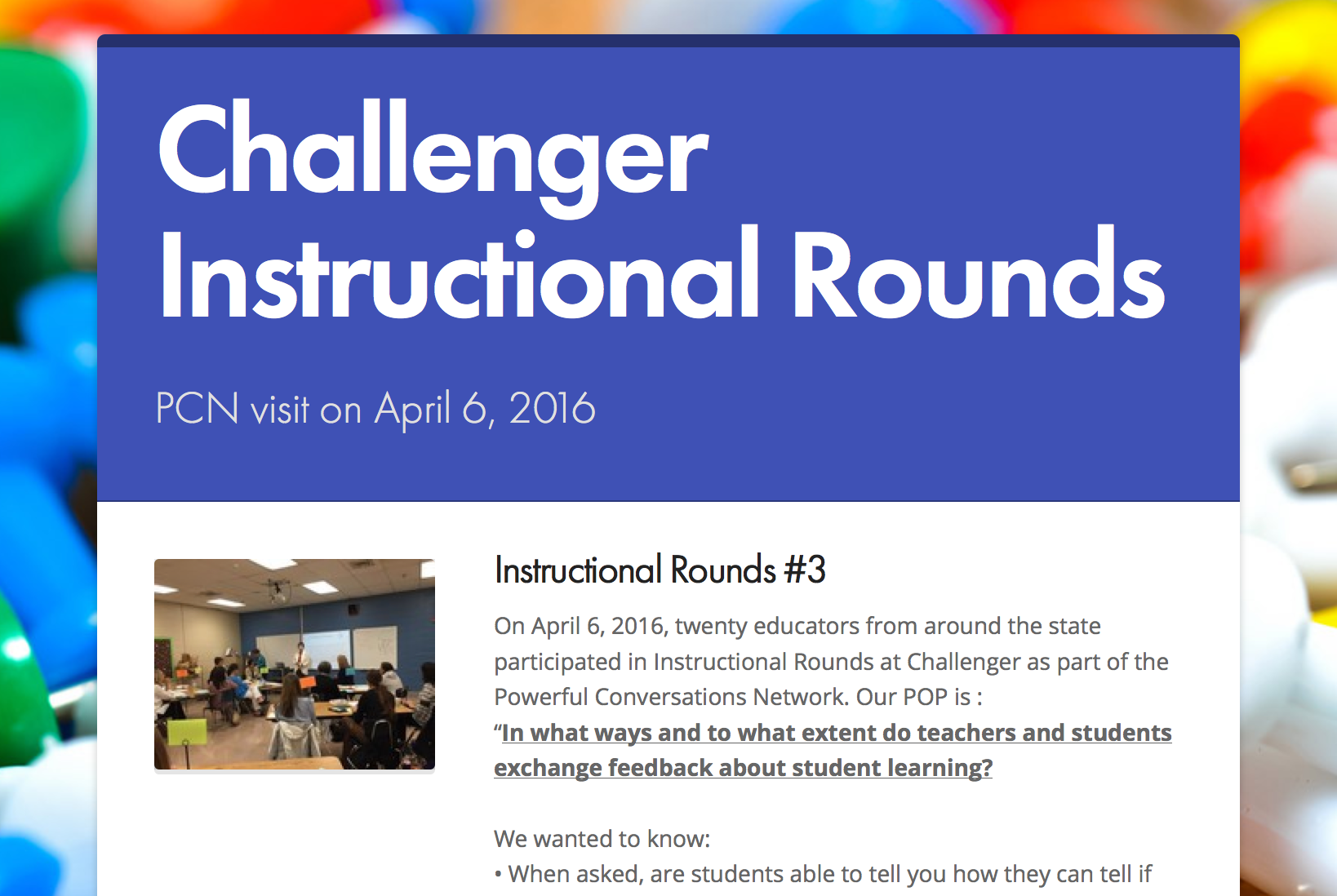

For a closer look at one school’s Instructional Rounds experience, visit this “Smore” page sent by Michele Wallace, principal of Challenger Elementary School, where we visited on April 6th. It does a nice job of capturing the Instructional Round there!

Focus on the students!

Instructional rounds require a lot of work and preparation. But elements of the process can be put to use in everyday situations. For example, the skill of “descriptive observation” can be used in a variety of ways: when watching a videotape of a lesson, or to do a quick check for instructional strategies in place, or during peer observations.

So don’t wait for an instructional round to practice descriptive observation. Next time you visit a classroom, find a student and ask them what they’re learning. Chances are that you’ll get an interesting answer like I did from the first-grader!

And you may just marvel at how much you learn when you focus on what’s being learned rather than just what’s being taught.

Related Post:

0 Comments on "A Closer Look at ABPC’s Statewide Instructional Rounds Program"