Did you know that while every student in Alabama is required to take Algebra, some schools offer “Algebra I-A” and Algebra I-B” over two years?

Did you know that while every student in Alabama is required to take Algebra, some schools offer “Algebra I-A” and Algebra I-B” over two years?

On the surface, this approach may seem reasonable, but as a recent analysis of federal data by the Florida-based ExcelinEd organization reveals, such practices can not only raise questions about course rigor but the opportunities students have for advanced math studies in high school.

In a first-of-its-kind report, ExcelinEd analyzed the latest data from the Office of Civil Rights in the U.S. Department of Education. The 2015-16 data was self-reported by 17,300 public school districts and 96,400 public schools and educational programs (a 99.8 percent response rate).

The data include information about access to math (Algebra I, Geometry, Algebra II, Advanced Math and Calculus), science (Biology, Chemistry and Physics) and college-credit bearing courses (Advanced Placement and dual enrollment).

In its late October report, College and Career Pathways: Equity and Access, ExcelinEd identified significant gaps nationwide in high school students’ access to college and career preparation courses.

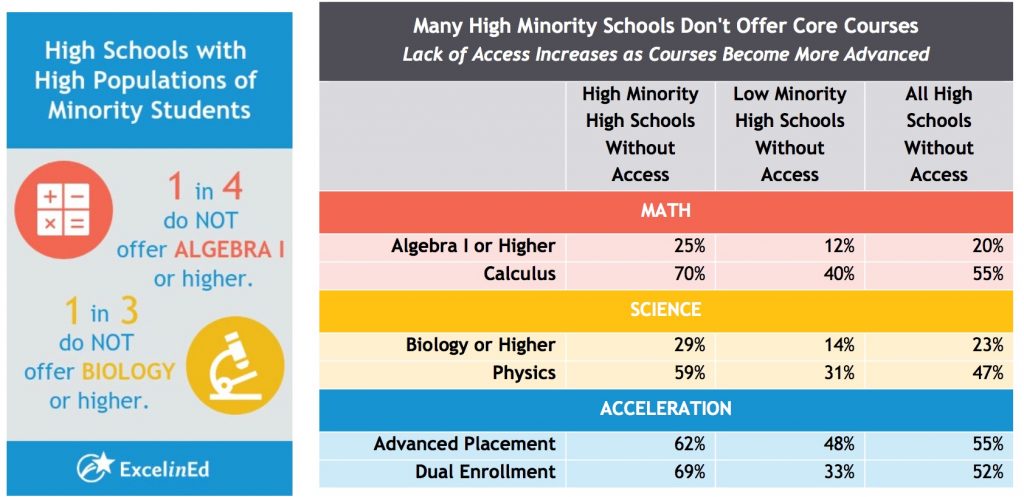

According to the report: “The data reveal a disturbing pattern of inequity: as the percentage of minority or low-income populations in schools increases, access to core courses decreases.”

Equity Issue 1: High Minority Schools

“Our analysis showed that students in high schools serving high populations of minority students are significantly less likely to have access to courses needed to prepare them for college and career. The data consistently reveal that as the percentage of minority populations in schools increases, access to courses decreases.”

Equity Issue 2: High Poverty Schools

“Students in high poverty high schools—schools serving high populations of low-income students—are also significantly less likely to have access to courses needed to prepare students for college and career. The data consistently reveal that as the percentage of low-income populations in schools increases, access to courses decreases.”

For Alabama students, the problem often doesn’t surface until later in students’ high school careers. Virtually all high schools in Alabama offer Algebra I, but many lack advanced math courses that students would take later in high school. Even if some advanced courses do exist, the problem remains if students spend two years to take Algebra I early in high school—and then run out of time to take advanced classes their junior or senior year.

You’ll find more details about the equity issues identified by ExcelinEd in their 21-page analysis, including:

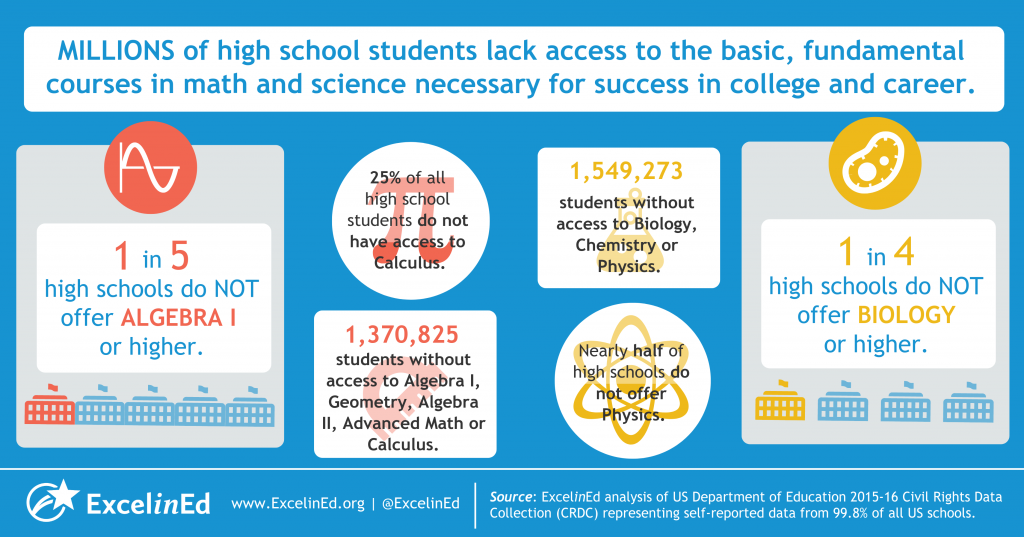

► The data show that across the country, nearly 1.4 million students attend public high schools that do not offer Algebra I or the subsequent progression of math courses expected by many colleges and universities for enrollment.

► An even greater number – 1.5 million students – attend public high schools that do not offer Biology or higher. And those are just the first core courses in the math and science progressions.

► More than half of our nation’s high schools don’t offer Calculus, meaning 4.3 million students can’t pursue this course. Nearly half (47 percent) of high schools don’t offer Physics, leaving 3.4 million students without access.

► The problem is not isolated to just a few states. According to the self-reported data in the CRDC, not a single state offers Algebra I or Biology in all high schools. The problem is also not limited to rural schools.

As the ExcelinEd report notes: “These courses open the door for students to pursue a range of challenging and vital careers. Research shows that students who take high-quality math in high school are more likely to declare STEM majors in college. And students who take Algebra II in high school are also more likely to enroll in college or community college. Many colleges expect students to have mastered these topics before they are accepted. Yet millions of students have no access.”

What Can We Do?

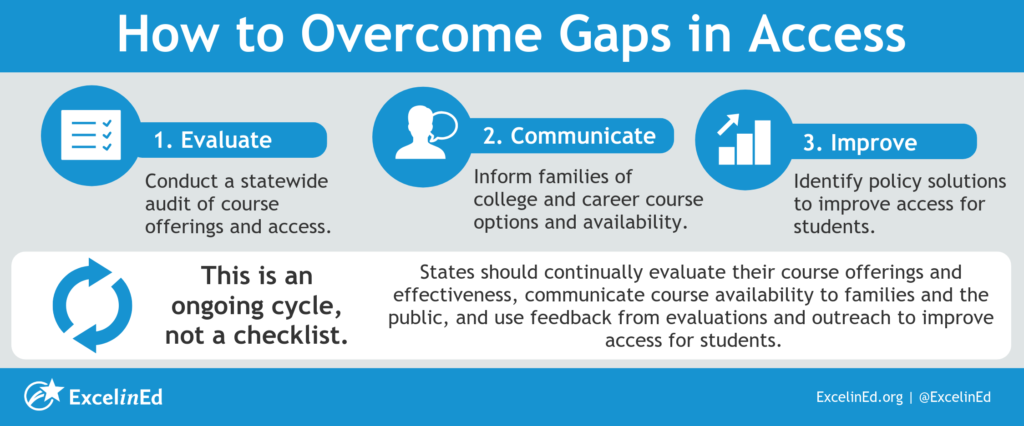

ExcelinEd has identified a three-step process states can consider using to overcome gaps in course access:

- Evaluate: Conduct a statewide audit of course offerings and access.

- Communicate: Inform families of courses necessary for college and career readiness and options to access those courses.

- Improve: Identify policy solutions to improve access for students.

ExcelinEd recommends that the process should be viewed as an ongoing cycle, rather than a check list. “States should continually evaluate their course offerings and effectiveness, continually communicate course availability to families and the public, and continually use feedback from evaluations and communications efforts to improve access for students.”

If you are interested in improving policies and practices to address these issues of access to STEM-related studies, I encourage you to read the report, learn more about the limitations of the data, and explore in more detail the solutions proposed by ExcelinEd — considering what they might mean for Alabama.

Thomas Rains is Vice President of Operations & Policy for the A+ Education Partnership.

0 Comments on "A New Report Underscores College/Career Pathway Issues for Students in High-Minority and High-Poverty Schools"