By Cathy Gassenheimer

By Cathy Gassenheimer

Executive Vice President

Alabama Best Practices Center

Cognitive Coaching is the brainchild of two of education’s most remarkable thought leaders – Arthur Costa and Robert Garmston. Since its introduction in the early 1990s, it has become one of the most respected systems of in-service teaching development ever devised.

In 2014, Art Costa and Bob Garmston teamed up with veteran school superintendent and educational leadership consultant Diane Zimmerman to distill the insights gained from 20 years of cognitive coaching’s evolution and make a concise and powerful case for deepening the capacity of educators so they can ensure all students learn.

Their 122-page book, Cognitive Capital: Investing in Teacher Quality, is even more relevant now than when it was written. Praised at the time of publication by leadership trailblazers Michael Fullan —

“The authors have positioned ‘cognitive capital’ at the center of understanding and developing teacher quality and have succeeded brilliantly.”

and Heidi Hayes Jacobs —

“In contrast to the persistent trend of simplifying teaching via reductive evaluation tools, [the authors] dive fearlessly into its complexities. Cultivating ‘cognitive capital’ is a refreshing new direction for educators to embrace.”

— the book is a short course in Cognitive Coaching and leadership skills proven to create a culture where both educators and students thrive. It is based on the belief that both educators and students prosper when they have some degree of autonomy and embrace high standards and continuous growth.

What is Cognitive Coaching?

Cognitive Coaching is based on the belief that self-directed learning can be more lasting and impactful. Organized around Five States of Mind, a cognitive coach helps the coachee discover and develop their own plan of action for growth and efficacy. The three phases of cognitive coaching include the planning conversation, the observation, and the reflective conversation.

One of the keys to cognitive coaching is the coach’s belief system. In Cognitive Capital, the authors make the case that “cognitive capital is maximized when the locus of control lies with those closest to actions taken—namely teachers” (p. 40). Effective cognitive coaches embrace equality and reciprocity when engaging in the coaching cycle, by seeking to establish a relationship of equal status or – as organizational culture guru Edgar Schein calls it – “equilibriating.”

The successful cognitive coach resists “advising” or giving unsolicited feedback, and instead uses active listening, pausing, paraphrasing, and questioning to advance the coachee’s thinking and planning and preserve the coachee’s ownership of the growth process.

The Five States of Mind

If you are familiar with Costa and Garmston’s work, then you know about the States of Mind: Efficacy, flexibility, consciousness, craftsmanship, and interdependence. “When the five states of mind are viewed as a whole, they create an inner tension that asks one to consider individual needs, the drive for autonomy, in the context of community. Together, they form a scaffold for thinking that is both interwoven and interdependent” (p. 21).

The authors summarize the Five States of Mind this way:

The capacity for efficacy. Humans long for competence, learning, self-empowerment, mastery and control.

The capacity for efficacy. Humans long for competence, learning, self-empowerment, mastery and control.- The capacity for flexibility. Humans survive by developing repertoires of response patterns that allow them to create, adapt, and change.

- The capacity for consciousness. Humans uniquely strive to monitor and reflect on their and others’ thoughts and actions.

- The capacity for craftsmanship. Humans yearn to become clearer, more linguistically precise, congruent in beliefs and actions, and integrated with an aligned work life.

- The capacity for interdependence. Humans, as social beings in need of reciprocity and community, grow in relationship with others. (p. 21)

The Five States of Mind help us grow and improve ourselves and others, and honor the fact that as thinking adults, no one likes being told what to do. Instead, we thrive when we work in collaborative cultures that support our growth. Teams that embrace psychological safety combined with a degree of autonomy become even better at what they do, sharing the belief that together they can reach every student.

A Master Class in Leadership and Coaching

Even though Cognitive Capital: Investing in Teacher Quality is less than 125 pages long, I took several days to reread it, giving myself time to reflect and learn. It is truly a master class in leadership and coaching. I’ve captured some of the big ideas below.

✻ Building Efficacy for Impact

Students of John Hattie’s work know that collective teacher efficacy has one of the highest effects on student learning. Both self efficacy and collective efficacy are built when teachers spend “time with others on personal and collaborative reflection about what effects their teaching has on student learning in a continuous spiral of inquiry. When teachers join together and become more conscious of their ability to make a difference, and they are in control of their multiple options, they display true craftsmanship” and both teachers and students succeed (p. 18).

✻ Effective Communication is Essential

Both nonverbal and verbal communication lies at the center of cognitive coaching. The coach is mindful of the nonverbal communication as well as what is said. The use of communication skills such as pausing, paraphrasing, acknowledging, probing and clarifying helps the coachee reflect and move forward.

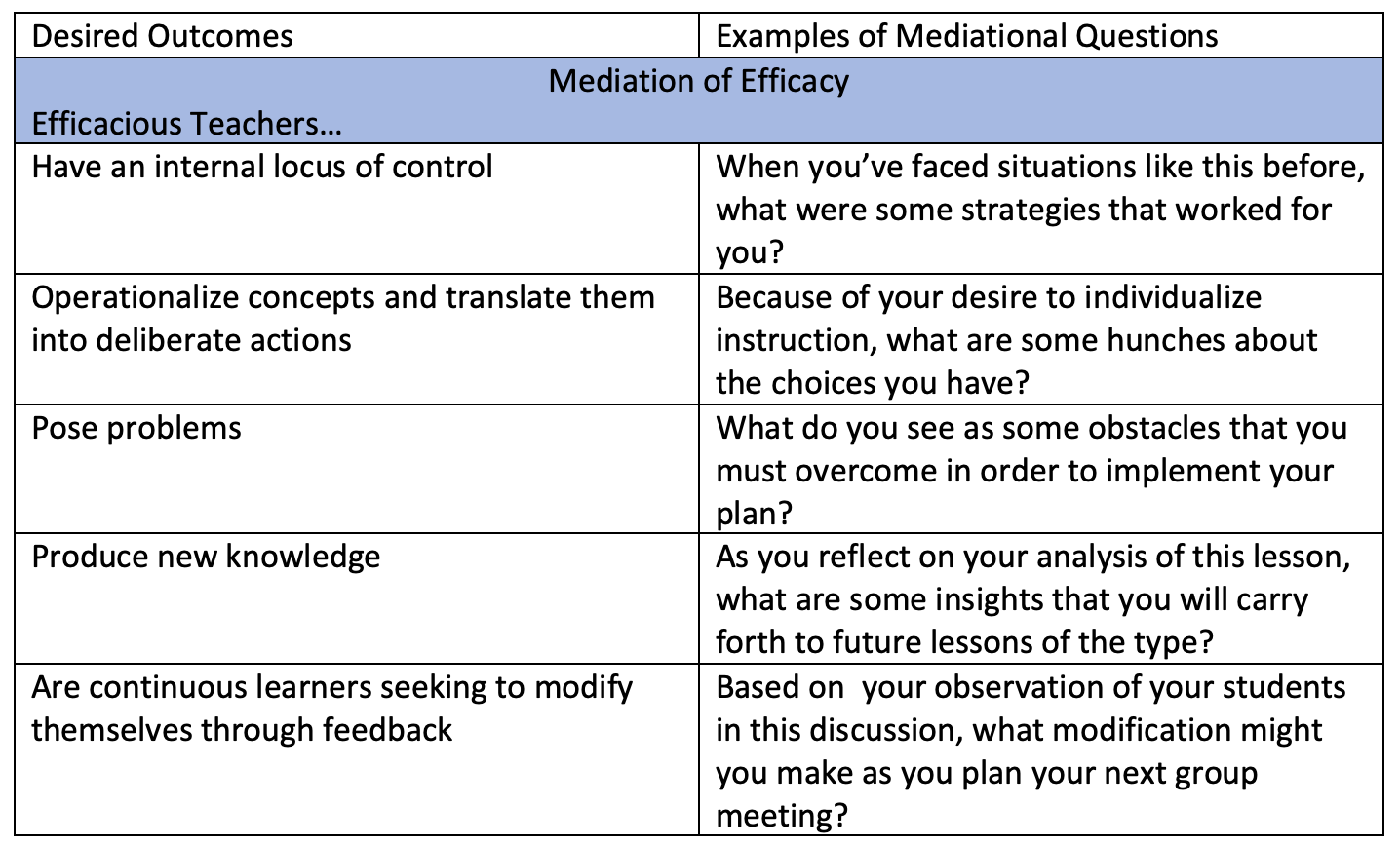

One of the most valuable parts of the book is a table which provides specific questions that can be used to strengthen each of the Five States of Mind during coaching. For example, here’s an excerpt from the table addressing efficacy:

✻ The Four Leadership Roles

Zimmerman, Costa and Garmston delineate four roles leaders play in managing and working with others: facilitating, coaching, consulting, and presenting.

When approaching a colleague, the leader should ask “for this situation, how might I engender the maximum cognitive growth while supporting maximum effectiveness?” (p. 40) While the authors favor the facilitating and coaching roles, there are times when presenting and consulting are appropriate for leaders to use.

Reminding the reader that to facilitate means to make easier, the facilitator “directs the procedures to be used in the meeting, choreographs the energy within the group, and maintains a focus on one topic and one process at a time…the more facilitators help groups succeed in getting important work done, the greater the sense of collective efficacy, a resource linked to student success” (p. 43).

The coach takes a nonjudgmental stance to help an individual move closer to a goal while also helping develop the needed knowledge and skills to reflect, plan, problem solve, and make decisions (p. 43).

Consultants and presenters are considered to be “information providers” by Costa, Garmston and Zimmerman. When leaders assume these roles, they take an expert stance and own the work and information. In most cases, when assuming these roles, the interaction between the consultant or presenter and the “client” tends to be perceived as hierarchical (p. 41).

✻ Talent Optimization Requires Open Dialogue

Near the end of the book, the authors make the strong case for leaders playing the role of facilitator and coach. “When leaders do not know how to make the space for dialogue and critical discussion, talents stay underground. Staffs do not get to know one another at a deeper level and the end result is conviviality, not true, thoughtful communication in community” (p. 99).

It’s All about Professionalism

“When professionals are given the encouragement to define their own learning, they have a heightened consciousness and a sense of awe about what they have yet to know,” the authors write in their summing up. “They seek out multiple viewpoints and enjoy being startled by a new idea. They persist and know that their work is to build their own personal craft knowledge and that of their peers. And they know that in the end, they must be able to declare, ‘We make a difference, because we have learned how to learn.’” (p. 103)

As we emerge from the pandemic and address our needs, the needs of our colleagues, and most importantly, student needs, the wisdom offered by Costa, Garmston and Zimmerman is more important than ever. Join me in being “startled by new ideas” and doing what it takes to develop our expertise and the expertise of others so we all thrive.

0 Comments on "Cognitive Capital: A Concise Guide to Supporting Teacher Growth"