By Cathy Gassenheimer

By Cathy Gassenheimer

Executive Vice President

Alabama Best Practices Center

Change is hard. My guess, however, is that – because of the pandemic and all of its ripple effects – most of us have changed more than we would have ever imagined.

Some images come to mind:

- Learning that Zoom meant more than going fast in a car;

- Learning how to wear (and keep up with!) a mask;

- Learning how to greet people without hugging or touching;

- Learning how to teach and learn remotely;

- Learning how to dress from the waist up;

- Learning how to count our blessings and get on with it, despite being afraid.

The events of the past 18 months, both large and small, have helped me be more open to change. That said, change is still hard, particularly when the need for personal improvement bumps against some long-held habits. So when I received a new research-based book about what it takes for humans to alter their behavior for the better, I was immediately drawn in.

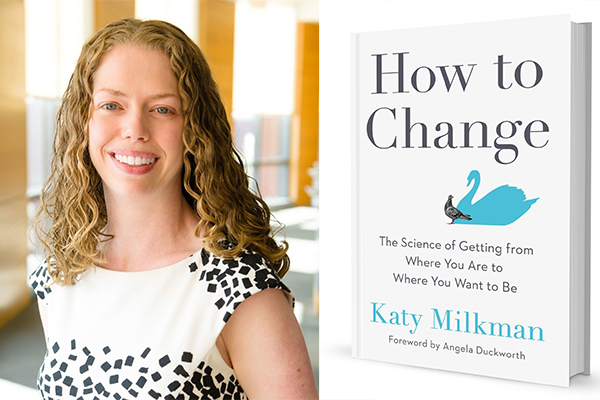

How to Change: The Science of Getting from Where You Are to Where You Want to Be comes with some impressive praise. Daniel Pink, Dan Heath, Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler, Carol Dweck, and General Stanley McChrystal are a few of the endorsers. And we can add Angela Duckworth, the proponent of the concept of “grit,” who penned the introduction.

About the Author

Katy Milkman is a Princeton grad, holds a PhD in Computer Science & Business from Harvard, is a behavioral scientist and teaches at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. Despite those lofty credentials, her writing is very accessible, clear, engaging, and full of stories that grab your attention. You can watch a short video of Milkman discussing habit-building here.

Katy Milkman is a Princeton grad, holds a PhD in Computer Science & Business from Harvard, is a behavioral scientist and teaches at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School. Despite those lofty credentials, her writing is very accessible, clear, engaging, and full of stories that grab your attention. You can watch a short video of Milkman discussing habit-building here.

The book is organized around what Milkman views as barriers to change: procrastination, forgetfulness, laziness, confidence, and conformity. To review the table of contents and read a short excerpt click here, where you’ll be treated to an introduction that includes Milkman’s riveting account of tennis star Andre Agassi’s own story of change.

Blank Slate vs. Fresh Start

I almost closed the book after reading this sentence: “If you want to change your behavior or someone else’s, you’re at a huge advantage if you begin with a blank slate—a fresh start—with no old habits working against you.” (p. 17)

Well, how often do we ever begin with a blank slate? Rarely if ever. If that’s what it took to change or build a habit, I was done! Fortunately, I turned the page and read this:

“There’s just one problem: true blank slates are incredibly rare.” Milkman’s point became clear in the next paragraph. One way to spur change is to create a sense of a blank slate, something that she calls a “fresh start” – a mindset we agree to give ourselves.

A fresh start offers a threshold that can nudge change for someone. The first example that comes to mind is January 1st, when many of us make new year’s resolutions. Other fresh starts can be at the beginning of the month or week, or during a major shift: a job change, a move, a new place to live…a time when people might be more open to change because it feels like a fresh start.

For many of us, these kinds of “fresh start” opportunities emerged during the pandemic. My fresh start was a commitment to regular exercise by walking at least two miles per day. Reading Milkman’s book provided some insights as to why I’ve been able to keep it up for 18 months.

Perhaps the key insight is that I took steps to make the daily walk pleasurable. Milkman refers to Mary Poppins’ admonition that “a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down.” I made sure that I found a walking route that had nice views and often got to watch the sun rise as I exercised.

Temptation Bundling and Mulligans

Milkman also suggests another commitment strategy: temptation bundling. This involves connecting what might be considered an indulgence to an activity you are trying to make a habit. For me, it was listening to audiobooks while walking.

I’m a voracious reader and love the idea of having novels read to me. Milkman suggests taking the temptation bundling a bit further by limiting your indulgence to only those times that you are building your new habit. After reading this tip, I decided to listen to audiobook fiction ONLY when I’m walking. I’ve found that to be a very powerful motivator!

Another tip that can make a difference in our persistence is the concept of a mulligan. If you’re a golfer, you know that a mulligan is a “do-over” shot without penalty, popular with weekend players. Milkman shares the idea of a friend who gave herself a limited number of mulligans during her habit-changing process. For her friend, it was an opportunity to skip exercise up to twice a week. Even though she rarely used two mulligans in a week, she had that option (which can lessen the ‘must-do’ stress).

Who Benefits the Most from Advice?

Michael Bungay Stanier, a noted coach and author, reminds us that advice-giving is not always wanted nor received well by the person being advised. Read my review of his book, The Advice Trap here. In the book, Stanier suggests four downsides to giving advice:

- It demotivates the advice-receivers

- It overwhelms the advice-givers

- It compromises team effectiveness, and

- It limits organizational change.

So, if that’s the case, why does Katy Milkman offer advice-giving as a tool for change? In a twist of thinking, she suggests that advice-giving can help us – the advice-givers – with our own change goals.

Milkman discussed this idea in a conversation she had with Grit author Angela Duckworth and Angela’s former doctoral student Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, who offered an example involving students and their grades. Here’s what Angela and Lauren told Katy:

Milkman discussed this idea in a conversation she had with Grit author Angela Duckworth and Angela’s former doctoral student Lauren Eskreis-Winkler, who offered an example involving students and their grades. Here’s what Angela and Lauren told Katy:

Angela: Well, the credit for the idea of advice-giving really goes to Lauren. We were studying grit and she came to me with the idea that if you want people to be gritty you should get them to give advice to other people about how to be gritty.

It was counterintuitive because you don’t tell people any new information. You don’t give them any tips or hacks. You just tell them to give other people advice. The idea that people could unlock information or wisdom inside themselves without being given anything, and then improve their motivation and performance, I thought was really intriguing.

Lauren: The intervention that had the most impressive effects raised kids’ grades. It was just one 8-10 minute session in which we said, “We think you have a lot of knowledge that you could share with somebody else.”

It was a really brief exercise where we asked them questions like, “How would you avoid procrastinating?” and “Can you write a note to another student who’s struggling to do better in school?” There were some multiple-choice questions like “What’s the most effective place to study?” This incredibly brief intervention seems to have had long-term effects [on the advice-givers].

Read more of the conversation in this article by Milkman.

One of my takeaways is this: if you’re trying to change, give yourself advice. Or if that’s too hard to conceptualize, imagine that you are advising a friend or colleague about the same change issue. You may open yourself up to your own deeper understanding.

Insights Abound

If you are contemplating making a change for the better, consider including this book in your required reading. As Daniel Pink notes, “This book is like having the smartest friend in the world whispering in your ear. You’ll want to send Katy Milkman a thank-you note.” And, if one of the things you want to change is being more intentional about thanking and appreciating others, writing that note might be a good first step!

Resource:

Dr. Katy Milkman is also host of Charles Schwab’s popular behavioral economics podcast Choiceology. Browse eight seasons of fascinating chats!

0 Comments on "How Can We Help Ourselves and Others Change for the Better?"