When I was in fourth grade, we studied the geography of different countries. We sampled “taste treats” (I loved all of them except the herring from Norway) and created color maps of each nation, adding topographical aspects of the country along with other key features.

When I was in fourth grade, we studied the geography of different countries. We sampled “taste treats” (I loved all of them except the herring from Norway) and created color maps of each nation, adding topographical aspects of the country along with other key features.

I was so excited about coloring in the maps that I cajoled my mom into buying a pack of colored pencils that came in a plastic pouch. The colors were vibrant, and I couldn’t wait to use them.

I vividly remember how I painstakingly outlined the shape of Norway. First, I used the blue pencil to highlight the west side of the country, where it met the northern Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea. Then I filled the interior with another one of my beautiful colors.

I vividly remember how I painstakingly outlined the shape of Norway. First, I used the blue pencil to highlight the west side of the country, where it met the northern Atlantic Ocean and the North Sea. Then I filled the interior with another one of my beautiful colors.

I added mountains with another color, then picked out a fresh pencil to create a legend. I kept adding and adding until my illustrated map shifted from a work of beauty to a cluttered mess with way too much “stuff.”

I learned a valuable lesson that day: Less can be more. Now any time I see anything that is overdone, I call it a “geography project,” harkening back to my overabundant art effort.

I was reminded of the importance of “less” when I finally found time in late spring to pick up the second edition of Mike Schmoker’s book Focus: Elevating the Essentials to Radically Improve Student Learning (ASCD, 2018).

I’d read the 2011 edition with interest and even blogged about it, noting Schmoker’s frank observation that to be really successful, “most schools would have to stop doing almost everything they now do in the name of school improvement” and focus only “on implementing what is essential.”

Less is Still More

What more does Schmoker have to say nearly eight years later?

What more does Schmoker have to say nearly eight years later?

His core message hasn’t changed. In fact, although many authors will tweak the subtitle of a second edition, Schmoker stays on target: “Elevating the Essentials to Radically Improve Student Learning” is still his urgent agenda. ASCD does add a quote to the cover of edition #2, from John Hattie: Schmoker has lit a fire in this book.

In his new introduction (p. 2), Schmoker once again stresses the importance of keeping a tight focus on what he believes are the three essential aspects of schooling:

- reasonably coherent curriculum (what we teach);

- soundly structured lessons (how we teach); and

- large amounts of purposeful reading and writing in every discipline

(authentic literacy – integral to what and how we teach).

I suspect few of you reading this blogpost would disagree. Yet, can you name a school that makes these three elements their primary focus and diligently works to keep them front and center, so their school doesn’t become one of my “geography projects”?

Focus on the Fundamentals

To ensure this type of laser-beam focus, Schmoker suggests that schools pledge to “declare a moratorium on new initiatives” – at least temporarily – to foster and strengthen these three fundamental elements.

In this new edition, Schmoker devotes the first part of the book to once again making the case for this particular trio of focal points.

According to Michael Fullan, decades of studies have demonstrated that the key to success is neither innovation nor technology. Rather, it is an abiding commitment to the “smallest number of high-leverage, easy-to-understand actions that unleash stunningly powerful consequences.”

This book argues that for the majority of schools, the three elements addressed here meet Fullan’s criteria better than all other initiatives combined; they are indeed few in number, exceedingly high-leverage, and easy to understand. You’ll find evidence for these claims in every chapter. For that reason, these actions all but guarantee “stunningly powerful consequences.” (Chapter 1)

Schmoker also devotes a chapter each to the first two elements: “What We Teach” and “How We Teach.”

Key Insights

Anyone who has borrowed one of my books knows that I religiously annotate as I read and keep a list of key insights written on the blank pages at the end of each book. Rather than spend more time outlining the book, I’ve decided to share and expand upon some of those annotations..

► “The achievement gap is a knowledge gap.” Schmoker calls on E.D. Hirsch’s 2008 Education Week article noting that students learn how to communicate, reason, evaluate and argue by “studying a rich curriculum in math, literature, science, history, geography, music and art and learning higher level skills in context…” (p. 25).

In a more recent piece, Hirsch suggests that “the achievement gap is a knowledge gap and a language gap” (Hirsch, Why Knowledge Matters, 2016). Background knowledge is essential to understanding what one reads and to enable students to identify key points or make inferences about what they are reading. Both Hirsch and Schmoker argue that an intentional effort to ensure that students possess or learn necessary background knowledge is critical to high-level learning.

► Reading to learn after we learn to read. I’ve been reading a lot lately about strategies to effectively teach comprehension, writing, and reasoning. And, while some aspects of the studies may differ slightly, all agree that teaching skill-based reading is necessary, but not sufficient.

After students learn to decode, the focus must shift to building comprehension and a richer vocabulary. In fact, Schmoker contends that “reading growth depends, more than anything, on our ability to build up students’ knowledge-base and vocabulary” (p. 27). Unless students can connect what they are reading to previous knowledge, their learning will be stymied, so building background knowledge is essential!

► Four primary skills for success. Schmoker calls on college-readiness expert David Conley to help us understand four essential skills that all K-12 students should have upon high school graduation (p. 39):

- Read to infer/interpret/draw conclusions.

- Support arguments with evidence.

- Resolve conflicting views encountered in source documents.

- Solve complex problems with no obvious solutions

► Writing is essential. The often-neglected focus on writing across the curriculum is troubling, not only to Conley and Schmoker, but also to colleges and private industry. In fact, Conley suggests one change that could have dramatic impact on college readiness: “increase[ing] the amount and quality of writing students are expected to produce” (Conley, 2007, p. 27; Schmoker, p. 41).

► Making students leaders of their own learning. Schmoker doesn’t use that expression – those words belong to Ron Berger in Leaders of Their Own Learning. But Schmoker would agree. He devotes considerable time to outlining the importance of formative assessment, which he likes to call “checking for understanding.” Schmoker provides a quick review of the research attesting to the effectiveness of the ongoing use of checking for understanding.

Basic Elements of Effective Teaching

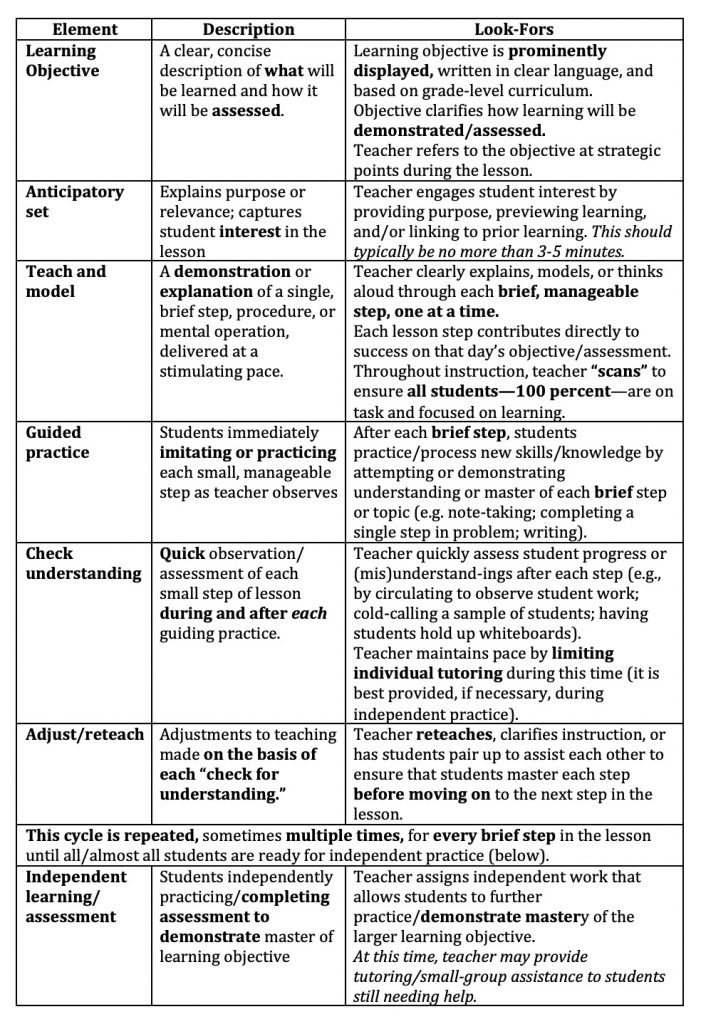

Schmoker doesn’t just “pontificate,” he identifies strategies teachers can use to help ensure students reach mastery. So, the final take-away for readers who have stuck with me this far, is a valuable table Schmoker has created summarizing those strategies.

The Book is Customized

The Book is Customized

The second section of the book addresses the third essential element: large amounts of purposeful reading and writing in every disciple (authentic literacy – integral to what and how we teach). This section features chapters on the four core subjects: ELA, social studies, science, and math. In a way, you can read this book as if Schmoker curated it just for you by selecting those chapters that interest you the most.

And, as you read, remember that less is more. Consider taking the time to look at your curriculum and other learning structures and activities currently in place and see if there are some things you can drop in favor of focusing on the main elements – the ones (to paraphrase Michael Fullan again) that “unleash powerful consequences.”

That way, you can avoid creating a “geography project” crowded with less effective “stuff” and instead ensure that your students are well-prepared for the next grade, college, or life.

0 Comments on "“Stunningly Powerful” School Improvement Begins by Sharpening Our Focus"