Some students begin their journey through middle and high school in high-visibility mode. They are active in class and in school life – “everybody knows their name.” But other students are at risk of getting lost in the crowd, which can impact their academic performance and their social-emotional growth. Teachers in Florence City Schools have begun proactive efforts to make sure every student is recognized and listened to. FCS instructional partners Krissy Edwards and Bryan Rebar explain.

By Krissy Edwards

By Krissy Edwards

Instructional Partner

Hibbett Middle School

It seems like each school year in my 15 years of experience, I have looked back and wished I had noticed more about some of my students; that I had listened to them more; that I had realized more about who they were.

Several years ago, Jenny Ozbirn, a fellow instructional partner in my district, told me about an activity she was leading with the Florence Freshman Center teachers. At a professional learning session, all the students’ names were listed on posters and teachers would check mark if they knew the students, maybe add another check mark if they knew more than their name, etc. Then they would look at all of the posters and see which students had very few check marks – those who needed someone to make a connection with them!

Several years ago, Jenny Ozbirn, a fellow instructional partner in my district, told me about an activity she was leading with the Florence Freshman Center teachers. At a professional learning session, all the students’ names were listed on posters and teachers would check mark if they knew the students, maybe add another check mark if they knew more than their name, etc. Then they would look at all of the posters and see which students had very few check marks – those who needed someone to make a connection with them!

When she told me about it, it just sparked my interest and curiosity about whether identifying students in this way could really help curb the feeling that each year some students seem to “fall through the cracks.” Since then, I had been looking for an opportunity to do the “Making Sure Each Child is Known” activity with the teachers in my own school.

Much has been written about the connection between building relationships and student achievement. We’ve heard the adage, “students don’t care what you know until they know that you care.” For the last couple of years, my district has been doing more to highlight the relationship-building aspect of teaching by bringing in keynote speakers on our in-service days as well as a summer learning session with Disrupting Poverty author, William Parrett.

This year, my school’s assistant principal decided to lead our faculty in a book study of Disrupting Poverty. All of these factors combined to provide the perfect timing, faculty readiness, and mindset for us to implement a “how well do we know our students” activity at our fall data day in October 2018.

This year, my school’s assistant principal decided to lead our faculty in a book study of Disrupting Poverty. All of these factors combined to provide the perfect timing, faculty readiness, and mindset for us to implement a “how well do we know our students” activity at our fall data day in October 2018.

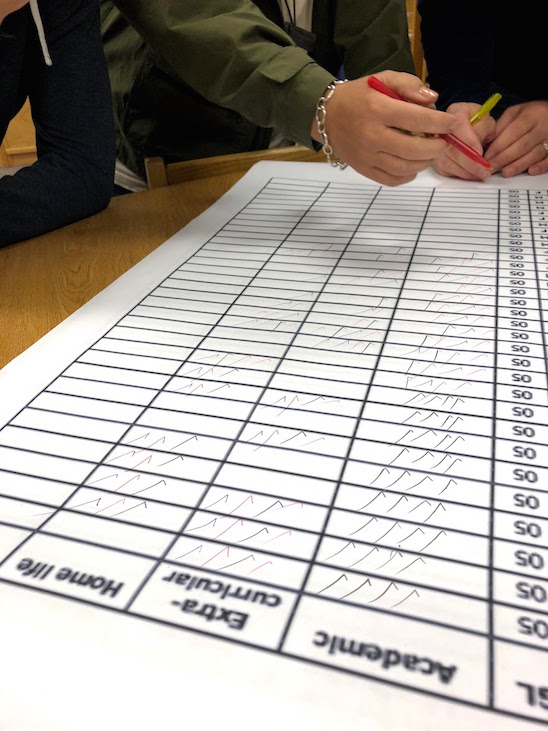

Similar to the Cold Springs (NV) Middle School strategy featured in this inspiring Edutopia video, I printed poster-sized lists of our students. Hibbett Middle School is organized according to a “team” concept, so I had rosters for each of our teams to look at together. The concept was simple: a list of student names with columns for teachers to place check marks indicating things they knew about each student: academics, home life, extra-curricular, and “other.”

My intentions were that teachers would simply scroll down the lists of names placing checkmarks and then examine the list for those who might be in danger of “falling through the cracks.” We have multiple data days embedded in our school year, so there would be time for investing in our relationships with students and checking back in on the lists on other meeting days.

Our agenda for the day only slated thirty minutes for this activity, but the timer was ignored as teachers became engrossed in discussing whether or not they “knew” the students. They were discussing connections that had been made and relationships that had been built. They were thinking about what likes, dislikes, interests, and family situations these kids bring to their classrooms each day.

Following the activity, I scanned each team’s posters into a document that I could email to them so that they could glance at the file as a follow-up and remember there are students who still need an adult at school to reach out to them.

In January, we had another data day during which we carved out time to revisit these lists. It was an opportunity to check back in with each other about how we further built those student relationships since the last data day.

We also added a checkpoint focused on student achievement. While “academic” was a column on the original lists, for this second pass, teachers were also asked to look specifically at students who were below where they needed to be for academic growth as measured by our winter assessments. This second look served as a reminder to touch base with those students who might need to know that an adult in this building truly cares about them as a student and as a person.

By Bryan Rebar

By Bryan Rebar

Instructional Partner

Florence Middle School

Our focus at Florence Middle School was also to ensure that we know our students. We wanted to make sure that each and every child has at least one adult that they can connect with on a deeper level – that the children we serve are not just a face, or just a name on a roster, or just a data point. We wanted to take the time to be intentional and reflect on how well we really know our kids, including our newcomers, who are often the most vulnerable.

We didn’t want this activity to be one that we just did once. Rather, we knew that eventually we would want build on this initial activity and include some type of student achievement measure from state accountability data. We also wanted a tangible way to manipulate and sort student information based on different attributes, which led to our development of a card for each student.

The cards could then be sorted by teachers and used to identify watchlists and special groups. We wanted teachers to be able to connect student data with the children they are serving, making predictions and estimates of student achievement based on their growing knowledge of the children they serve.

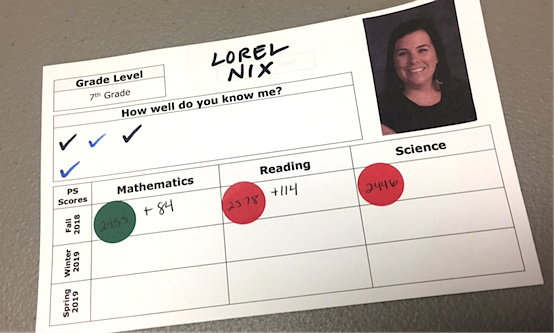

In the beginning, we particularly wanted to know how well we knew our new students. We took all of the students on the school roster and printed labels with their name. To start the sort, we wanted teachers to answer the question, “How well do you know me?” The only information affixed to the card was the student’s name, his or her grade level, and the actual color of the card. This was used to indicate a sub-population of students.

This is a sample, featuring our 7th gr. counselor,

This is a sample, featuring our 7th gr. counselor,

showing the information we placed on the cards.

We set up a system to help identify students with special needs and ELL students. We printed regular ed students on white note cards, SPED on blue note cards, and ELL on purple note cards. No where on the card was it written that these students fell into these categories.

Directions: Place a black check mark in the box if you know the student and something personal about their home situation. Place a blue check mark in the box if you know the student by name only.

We spread the cards out over the tables of the cafeteria and gave the teachers time on a PD day to place a check mark next to each student’s name. We asked teachers to take two colors of pens to make their marks – a blue check if they knew of the student by name and a black check if they knew something more than just their name.

As the teachers circulated around the cafeteria placing checks on the cards, student case managers quickly picked up on the color coded system. 7th Grade teachers progressed through their grade level and circulated around the cards of their previous students, sharing bits of information about the students to their new teachers. It was a challenge to identify how well teachers knew a student based on this information alone since we did this at the beginning of the year.

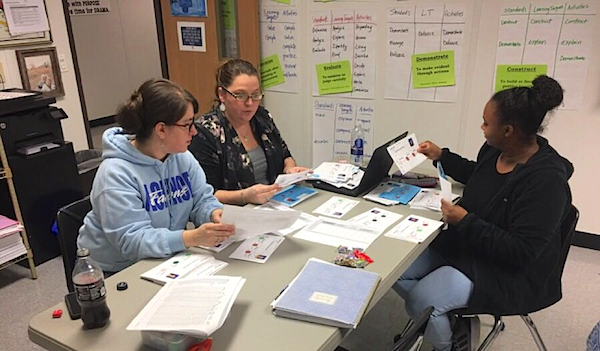

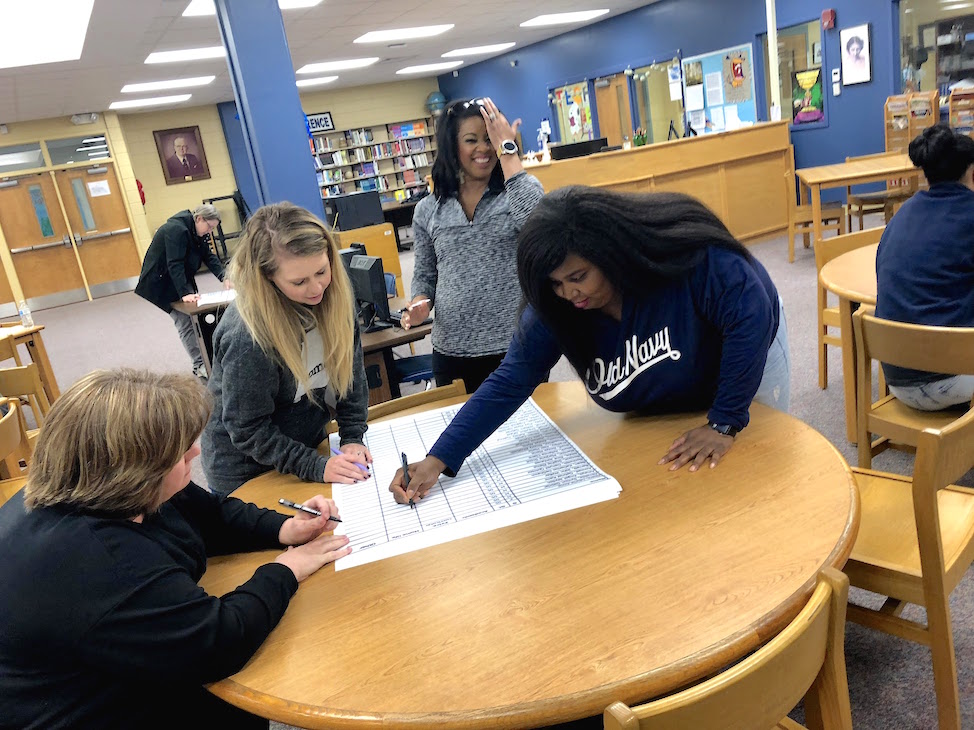

A group of 7th Grade ELA teachers from FMS work together to identify student target gains.

A group of 7th Grade ELA teachers from FMS work together to identify student target gains.

After the teachers had the opportunity to make their checkmarks, we went through and looked for trends in the information we collected. We noticed that for both 7/8 grade levels there was a threshold for the number of checkmarks a student had.

We generated a list of the students who had significantly fewer checkmarks and looked at how many black and blue checks they each had. Many of these students ended up being new to the school. This list was given to our counselors. The counselors then pulled in the students and had conversations, and our teachers and admin also followed up with these students.

These activities have given both teachers and administrators a collective platform to discuss how well we know our students. As we continue to pursue this activity, we are able to work together to identify the students that have extenuating circumstances, as well as students that may need special attention.

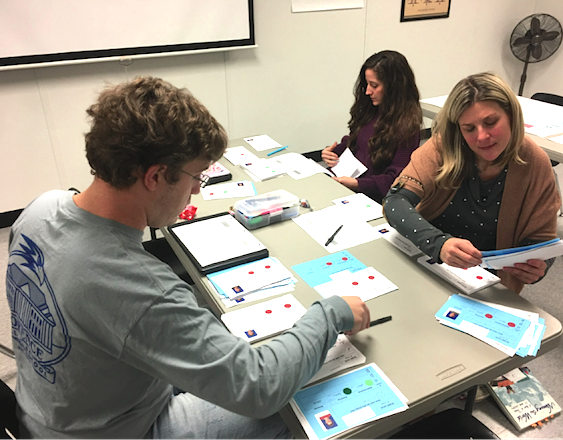

8th Grade ELA teachers from FMS sort the notecards to make predictions on student achievement

8th Grade ELA teachers from FMS sort the notecards to make predictions on student achievement

for the upcoming winter Reading Performance Series assessment.

Krissy Edwards is the Instructional Partner for Hibbett Middle School in Florence City Schools. Krissy began her teaching career in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, teaching middle school language arts. She has also taught middle school language arts and computer classes in Madison County and Florence City. She holds a BS in Secondary English Education and a Master’s in Computers and Applied Technology.

Bryan Rebar is the Instructional Partner for Florence Middle School in Florence City Schools. Bryan began his teaching career in Cincinnati, Ohio, teaching grades 4-7 (reading, math and science) in a school for students with Autism and other spectrum disorders. He also taught middle school science in Texas and in the Florence City Schools. He holds a BS in Education and a Master’s in Middle Childhood Education with a focus on Reading, Mathematics, and Science.

0 Comments on "Florence City Schools: “Making Sure Each Child is Known”"