Cathy and I want to point you to a powerful piece of writing. It’s a story by Marc Tucker about the impact that storytelling has on the education policies we endorse and the education politics we embrace. It might be summarized this way:

Cathy and I want to point you to a powerful piece of writing. It’s a story by Marc Tucker about the impact that storytelling has on the education policies we endorse and the education politics we embrace. It might be summarized this way:

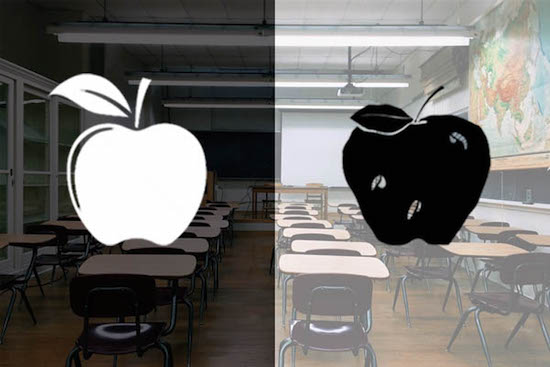

The two major narratives around schools divide us from seeing the truth and making the change that is really needed. (Tweet, 7/31/18)

Tucker, some may recall, is the long time leader of the National Center on Education and the Economy (NCEE). Marc’s commitment to teaching quality and student success stretches back to his authorship of the 1986 Carnegie Report, A Nation Prepared: Teachers for the 21st Century and his leadership in creating the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards in the mid-1990s. On a parallel education front, his tireless focus on America’s choice of “high skills or low wages” has continued for nearly three decades.

As much as anyone who has been in the “education reform business” through the eras of A Nation at Risk, College & Careers, No Child Left Behind, Common Core State Standards, and the Every Student Succeeds Act, Tucker has learned from hard experience about the important role that “story framing” has in the ever–ongoing public school debate.

Two Narratives – Same Classroom (Source: NCEE)

Here’s an excerpt from Tucker’s recent column for Education Week, which also appears at the NCEE blog, “How Stories, More Than Facts, Shape the Possibilities for Education Reform.” After sharing two typical and contrasting “stories” we often hear about the condition of the public schools (you will recognize them immediately!), he writes:

Communications experts talk about the way people frame issues in the same terms that I have just described the (education) stories they tell each other. The way I frame an issue will determine whether I am ready to listen to your “facts.”

There are at least two reasonable ways to respond to this analysis if you are trying to get someone or some group of people to do something: either figure out how they frame the issues and then make a pitch that fits their frame or try to change the way they frame the issues.

Not all frames are equal, though. If you want to change the way people frame the issues, one of the most effective ways to do it is to scare them. Tell them a scary story about people who are out to cheat them, take their jobs away, murder them or just dismiss them and their way of life. Do this effectively, and people will be more than willing to ignore the facts, turn their backs on values they have long embraced and trust people to lead them whom they would never otherwise have trusted. Fear is a powerful motivator, and very effective in the hands of effective storytellers.

But there are other frames. Some are grounded not in fear but in our better angels. These are frames of hope. They hold out the prospect of a better life for all, if only we will work together. They paint a picture in which everyone sacrifices a bit now so all will do better later. These are frames of not just hope, but also of trust, because no one will sacrifice now if the result of that is simply that their neighbor takes advantage of their sacrifice to grab as much as possible. To make a narrative of shared sacrifice work, I have to trust my neighbor.

Some years ago, watching educational policymakers and advocates come together repeatedly to address persistent problems in public education, I realized that, even though all of them thought the system was broken, none of them thought it could be fixed. So, they came to the table resigned to working within a broken system. Each one approached the table making the arguments they had always made, hoping to get a little bit, but not prepared to give up much of anything. These endless rituals always ended in some form of stasis, like a Japanese Noh play in slow motion.

It occurred to me that there was an alternative to this formalized dance. Suppose, I thought, one could create a table at which these players could not find their accustomed place? Suppose, in other words, you could put a proposition on the table that, for each player, offered the promise that they could get much more of what they wanted than they had ever imagined getting, but each would also have to give up more than they had ever imagined giving up to get it? I have, ever since, tried to create such tables. Doing it requires that the players give up their narratives….

READ Marc Tucker’s complete essay here.

Here is the Education Week version.

Photo credit: Marc Tucker (Education Writers Association)

John Norton has been a communications consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center for more than 20 years and currently serves as editor for the ABPC Blog. He’s also the founder and co-editor of MiddleWeb, an online resource for educators working in grades 4-8. He is a former Vice President for Information at the Southern Regional Education Board and was an award-winning education reporter in South Carolina. He lives the mountain life in Little Switzerland NC.

0 Comments on "What Stories Do We Tell About Our Schools?"