We all know that reading is an essential skill for success. Unfortunately, many Alabama students aren’t yet ready to learn at high levels. Fortunately, for most of these students, there is a pathway forward. And, it is highly dependent on the type of teaching the student receives.

We all know that reading is an essential skill for success. Unfortunately, many Alabama students aren’t yet ready to learn at high levels. Fortunately, for most of these students, there is a pathway forward. And, it is highly dependent on the type of teaching the student receives.

To help teachers improve the reading comprehension skills of their students, Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey teamed up with John Hattie to write Visible Learning for Literacy: Implementing the Practices That Work Best to Accelerate Student Learning.

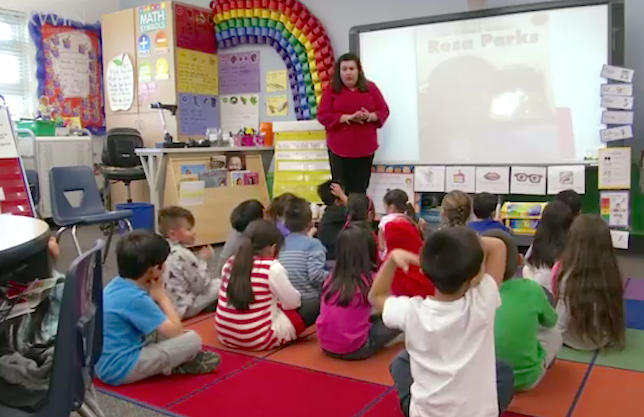

The book is a just-in-time resource for teachers of all grade levels and in all subject areas who want to ensure that their students can effectively read, understand, and explain what they are learning. Each chapter is accompanied by several videos of teachers or the authors discussing or demonstrating a specific strategy. You can browse all 19 videos here.

How the book came to be

Visible Learning for Literacy was the result of Fisher and Frey’s study of Hattie’s Visible Learning and Visible Learning for Teachers and a chance meeting with John Hattie himself. During their dialogue with Hattie he stressed that a key to student understanding and transfer is addressing surface-level learning in tandem with deep learning.

Hattie’s point resonated with both Fisher and Frey, and end product was this book! In this two-minute video, Nancy Frey summarizes the three key takeaways from the book.

The book is organized into five chapters:

- Laying the Groundwork for Visible Learning in Literacy

- Surface Literacy Learning

- Deep Literacy Learning

- Teaching Literacy for Transfer

- Determining Impact, Responding When the Impact is Insufficient, and Knowing What Does Not Work

(See the complete table of contents here. It’s rich with detail)

A book you might use every day

Visible Learning for Literacy is a perfect companion book to both Hattie’s research and Ron Berger’s Leaders of their Own Learning, which we’ve used in our networks’ professional learning experiences.

Visible Learning for Literacy is a perfect companion book to both Hattie’s research and Ron Berger’s Leaders of their Own Learning, which we’ve used in our networks’ professional learning experiences.

In the case of Hattie’s research, the book provides examples of identified practices that, if used effectively, can help students experience a year’s worth of growth. And, for Leaders of Their Own Learning, the book supplies more detailed information about success criteria and what measures of success look like.

In fact, if I was teaching, this book would be an essential source I would use almost daily. For example, when pointing to the importance of learning targets and success criteria to both surface and deep learning, the authors highlight four strategies:

- Showing students graded examples of an A, B, and C piece of work, and discussing how they differ

- Giving students the scoring rubrics at the outset and teaching them what they mean

- Sharing last year’s student work in the same series of lessons

- Building a concept map with students up front to show the interrelationships between the various parts they will learn about (p. 22)

Mistakes as the hallmark of learning

When teachers use success criteria, it more rapidly surfaces student errors. And, according to the authors, errors “should be expected and celebrated because they are opportunities for learning” (p. 31). In fact, if students aren’t making mistakes, the authors contend the learning is probably not at the appropriate level of challenge or the teacher is covering something that students have already learned.

Success begins with acquisition and consolidation

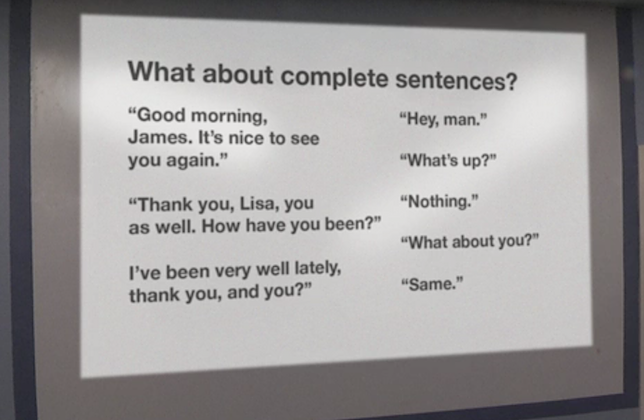

Building both surface and deep learning requires two phases: acquisition and consolidation. When students are presented with and learn the initial facts about a concept being taught, they are acquiring that knowledge. But, to be able to use and transfer that knowledge, they have to consolidate what they learn. Consolidation requires repetition, practice, rehearsal, and feedback.

And, I found it particularly important to understand the concept of “overlearning.” Surface learning often requires overlearning many basic tasks. For example, I remember learning how to tie my shoe when I was very young. A friend taught me a version where I made two “bunny ears” and then tied them together. I still remember spending a good part of the afternoon learning how to do that.

My mom was initially chagrined that I had learned to tie my shoes “the wrong way.” That concern quickly abated when she realized that was one less thing she needed to do for me, as she had two younger children to tend to! Later, I “overlearned” the “right” way to tie my shoes, although when I’m tired, I’ll often revert to the tried and true bunny ears version!

Beginning reading: Constrained and unconstrained skills

We all know that teaching students how to read requires a focus on phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and comprehension. What I hadn’t thought about before was how some of these important skills are “constrained,” while others are “unconstrained.”

The first three (phonemic awareness, phonics and fluency) are constrained because they have “boundaries.” There are 44 phonemes, 26 letters, and “a finite number of letter combinations that represent the sounds. And, there is a limit as to the rate of reading one can sustain without sacrificing accuracy and meaning” (p. 46).

But, vocabulary and reading comprehension are considered unconstrained skills because we continue to expand them throughout the learning process and our entire life.

And, here’s a key insight about the critical importance of intentionally teaching these constrained skills so students can move on to the important unconstrained skills of vocabulary development and reading comprehension:

(C)onstrained skills do have a shelf life, in that once they are learned, they no longer need to be taught. Thus, attention to constrained skills instruction does fade after the first years of school as students acquire them. In turn, vocabulary and reading comprehension take on an even more prominent role than in the primary years. The role and importance of phonics instruction and direct instruction should be considered within the context of constrained and unconstrained skills (p. 46).

As I read that excerpt, I was reminded of the experience of learning how to ride a bike. Initially—at least for most of us—training wheels are placed in the bicycle. Once we master balance, there is no longer a need for the training wheels. In fact, if a parent tried to put the training wheels back on the bicycle, it would most likely befuddle and frustrate the child!

Yet, I’ve been in classrooms where every elementary student is going through a fluency station where a peer times their reading, even if they are already reading fluently. For more fluent students, their time would be better spent adding to their vocabulary and deepening their comprehension.

It’s about the teaching

Throughout the book, the authors point to Hattie’s research and make the important point that most learning problems can be traced back to the teaching. Teachers must become students of their own teaching and impact, and make the necessary adjustments when students don’t learn. The book is full of suggestions, templates and advice about what to do when the learning falls short.

Throughout the book, the authors point to Hattie’s research and make the important point that most learning problems can be traced back to the teaching. Teachers must become students of their own teaching and impact, and make the necessary adjustments when students don’t learn. The book is full of suggestions, templates and advice about what to do when the learning falls short.

The authors say it the best in their closing sentences:

What teachers do matters when they monitor their impact and use that information to inform instruction and intervention. What teachers do matters when they reject instructional practices that harm learning. And best of all, what teachers do matters when they make literacy learning visible to their students, so students can become their own teachers” (p. 167).

0 Comments on "Fisher and Frey Target Hattie’s Most Effective Literacy Practices"