If you had a child entering kindergarten next year – and some of you who are reading this might – what would be your aspirations for him or her?

If you had a child entering kindergarten next year – and some of you who are reading this might – what would be your aspirations for him or her?

You’d probably want them to be happy, have friends, behave, and do well in school. Look at that last attribute: Do well in school.

What does that mean?

Back when I was in elementary school, it meant getting good grades and staying out of trouble. Students who did those two things sailed through the grades.

But were they ready for the real world, citizenship, and perhaps becoming parents themselves in the not so distant future?

Tom Hoerr, in his new book, The Formative Five: Fostering Grit, Empathy, and Other Success Skills Every Student Needs, argues that success in school today is much more than getting good grades and staying out of trouble.

Tom Hoerr, in his new book, The Formative Five: Fostering Grit, Empathy, and Other Success Skills Every Student Needs, argues that success in school today is much more than getting good grades and staying out of trouble.

After sorting through dozens of possibilities (see his list in the Introduction), Hoerr identified five skills that he believes to be essential to developing a well-rounded student and future adult.

- Empathy: Learning to see the world though others perspectives.

- Self-control: Cultivating the abilities to focus and delay self-gratification.

- Integrity: Recognizing right from wrong and practicing ethical behavior.

- Embracing diversity: Recognizing and appreciating human differences.

- Grit: Persevering in the face of challenge.

While these attributes may seem to rise above the level of “skills,” Hoerr argues that:

Significantly and encouragingly, the Formative Five skills are teachable, regardless of the students’ ages. Of course, it is most effective to teach the skills when students are younger and more receptive, but they must be taught regardless of when this happens, because students can always learn to adopt them.”

Inside the book

The book has eight chapters – one chapter on each of the “Formative Five,” an introduction, a chapter about the importance of a collaborative school culture, and a conclusion. An appendix features self-assessment surveys designed for students to gauge their proficiency for each of the five skills.

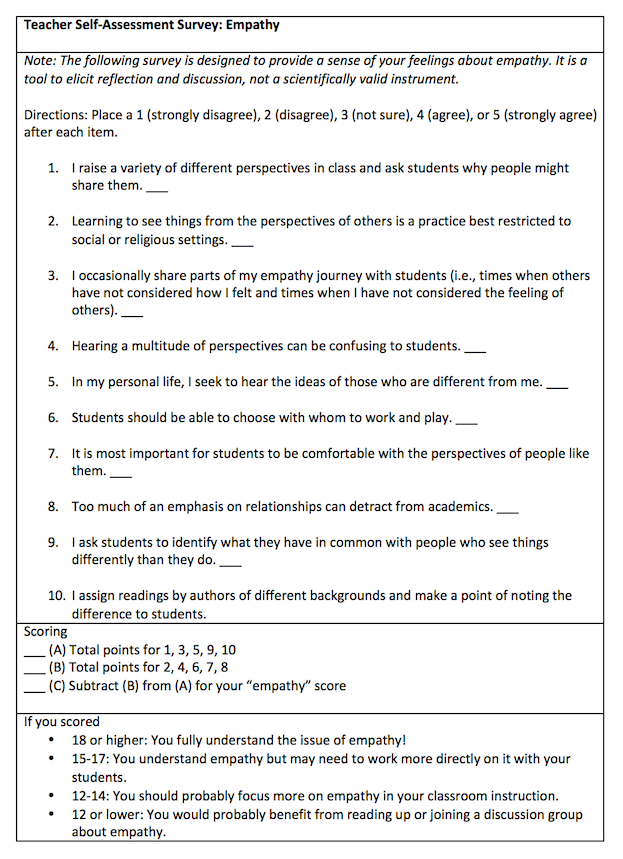

I found the self-assessments to be worth the price of the book alone. In addition to the student surveys, most chapters contain a self-assessment for teachers to gauge their propensity for each of the five skills. I’ve created a facsimile of the Empathy self-assessment to give readers the idea:

The chapters addressing each of the five skills are organized to help readers both understand and take action. Chapters begin with an explanation of the specific skill, accompanied by a featured self-assessment for teachers. The explanation is followed by steps to develop that specific skill. Finally, the chapter suggests specific strategies for developing the skill, followed by a list of resources.

For example, following the empathy theme, some of the suggested strategies for developing or strengthening empathy include:

- Have students engage in community service

- Help students recognize and understand the perspectives of others

- Encourage students to consider situations from a variety of perspectives

- For elementary students: teach students the difference between sympathy and empathy; Use games and simulations to helps students see situations from others’ perspectives

Throughout the book, Hoerr’s ideas reinforce his opening epigram from Ralph Waldo Emerson: “Character is higher than intellect.”

School culture building

One of my favorite chapters was the chapter on culture. Titled, “Culture is Key,” Hoerr suggests that schools must be intentionally organized to promote the Formative Five, and that teachers must model the behaviors for students.

Hoerr connected school culture to John Coleman’s Six Components of a Great Corporate Culture: (1) mission, (2) values, (3) practices, (4) people, (5) narrative, and (6) place. This explanation is accompanied by a useful table, which features a list of questions to consider about each of these six components.

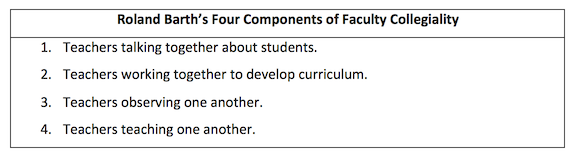

A school culture that incorporates the Formative Five is one that fosters creativity and collegiality. Referring on Roland Barth’s four components, Hoerr added a fifth: “Teachers and administrators working on learning committees together” (p. 145).

We’re all adults and children here

Near the end of the book, Hoerr connects the use of the Formative Five to the adults working in school. He reminds us that adults are “simply older children” and need attention as well (p. 167). “In the same sense that students need to feel cared for and known, so too, do teachers. Teachers must know that principals want to help them succeed and understand that mistakes are part of the process” (p. 163).

Other adults are important, too, suggests Hoerr. To make his point, he shares some of the letters he wrote to families when he was Head at the New City School in St. Louis, Missouri. These letters range from topics about technology, to Formative Five skills, school schedules, and more. He also includes some letters from teachers about specific learnings or extracurricular activities – all to demonstrate effective communication that broadens “school culture” to include families and guardians.

Other adults are important, too, suggests Hoerr. To make his point, he shares some of the letters he wrote to families when he was Head at the New City School in St. Louis, Missouri. These letters range from topics about technology, to Formative Five skills, school schedules, and more. He also includes some letters from teachers about specific learnings or extracurricular activities – all to demonstrate effective communication that broadens “school culture” to include families and guardians.

If you are looking for a book that can help you, as an educator, develop the “whole child” to ensure success in school, life and citizenship, pick up a copy of The Formative Five. The resources and ideas might help you start the new year off right!

Browse the Introduction and a study guide to The Formative Five

0 Comments on "Five Formative Skills Can Help Assure Our Students’ Success"