How does the principal of a large PK-6 elementary school – a former reading coach well-versed in ARI fidelity – learn to lead a school-wide transformation to project-based learning?

With the help of some pushy experts, she says. Experts who happen to be teachers in her own school.

Julia Gordon “Julie” Pierce came to Gulf Shores Elementary School as principal in 2008, after 15 years as a teacher and reading coach and a three-year apprenticeship as an assistant principal. An Alabama native, Pierce had a relatively brief first career as an accountant (“my dad urged me to go into business instead of teaching”), then earned her masters degree from UAB and taught in elementary and middle grades for 13 years, some spent in Florida.

Most of the Alabama part of Julie Pierce’s career has been spent in Baldwin County, where she was trained by the Alabama Reading Initiative in 2002 and coached at Summerdale School as it added 6th, 7th and 8th grades in just three years time. “I learned a lot about the progression of readers as they move up through the middle grades,” she remembers.

The impact of explicit instruction

Although Pierce earned her masters in the late 80s when UAB was nationally known for its commitment to whole-language instruction, she has high praise for ARI’s impact on early reading success in Alabama. “One of the things I loved about ARI and No Child Left Behind was that suddenly there was accountability,” she says. “Primary grade teachers suddenly had to be able to say to the public, ‘Yes, this child can read.'”

Pierce knows from her own coaching experience that the explicit instruction advocated by the ARI training reached not only the children who were “ready to read” when they entered the primary grades, but the hard-to-teach students from challenging circumstances who in the past would have struggled with literacy issues throughout their school careers.

“The ARI approach required lots of practice, and all five components of reading instruction had to be addressed. We taught those basal programs to fidelity,” Pierce says. “Things began to turn around; we saw almost all kids reading and they were able to go forward through school owning that critical skill.”

It was this perspective that Pierce brought with her when she became the principal leader at Gulf Shores Elementary. She says she never abandoned her belief, nurtured at UAB, that exploratory learning experiences were what helped children become deep thinkers and problem-solvers. But she was determined to be very protective of the explicit teaching strategies that were moving Alabama toward near-universal K-12 literacy.

In 2008, those strategies were very important in her Title I school, which was becoming increasingly diverse as the real estate bust (and later the BP oil spill) severely impacted the resort area’s economy.

A timely intervention

During Pierce’s first few years at GSES, she says, “the intermediate and upper grades teachers were very happy because they were finding that most all the students coming into their classes were readers.” She heard few complaints about explicit instruction in those early days.

By 2010, however, Baldwin County was giving increased attention to the potential of technology integration and the needs of digital learners. A number of teachers in the system became involved in eMints, the well-known Missouri-based technology integration program offering training in an instructional model that:

- promotes inquiry-based learning

- supports high-quality lesson design

- builds community among students and teachers

- creates technology-rich learning environments

As teachers gained expertise through the eMints professional training, an interesting phenomenon began to occur, recalls Pierce (who not only has a good sense of humor but a willingness to laugh at herself).

“The fourth grade teachers, in particular, started knocking on my door and yelling at me that teaching the basal reading program ‘hook, line and sinker’ to fidelity was killing their enthusiasm for the teaching of reading and, on the part of students, for reading itself.”

Pierce admits she was of two minds on the subject. While she also sensed that kids and teachers in the upper grades were bored with reading, she wasn’t going to risk the hard-won literacy gains made thanks to explicit instruction.

Two of the loudest door knockers, Pierce says, were eMints-trained teachers who had specially equipped classrooms with 1-2 computer ratios and hundreds of hours of technology-oriented professional development.

“Now they were coming back to me and saying, ‘You sent us to eMints, but what they are being paid to teach us, you won’t let us do!’

“My response was, ‘No way – we are teaching reading to fidelity!'”

Even so, that “other mind” of Pierce’s was nagging at her. She recalls that she had some conversation with ARI regional coaches. “I said, hey, the teachers are beginning to get disgruntled in the upper grades.” Still, despite the persistent knocking at her door, she continued to resist until one memorable day when she was observing in a 6th grade classroom.

“I am not kidding,” she relates. “This is what the teacher said: Okay, today we’re going to read this required story. Last year’s sixth graders hated it and y’all probably aren’t going to like it much better – but y’all find a partner and y’all start reading.”

Pierce immediately began to search for some action to take. She knew of an ARI workshop (Literacy Across the Curriculum) designed to help middle grades teachers increase student engagement in text. “I came back to my office and I called ARI and said ‘I need y’all down here immediately!’ So we set it up and they did a 2-day workshop with the 4th, 5th and 6th grade teachers, around the before-during-after reading strategies.”

Here the plot thickens.

“The teachers loved it,” Pierce remembers, “but what happened was the two eMints teachers went storming up to the ARI regional reading coach and to our local reading coach, and said, ‘We are furious with our principal. She will not listen. What you are teaching us in this workshop is exactly what eMints is teaching us with project-based learning. But she won’t listen.'”

This happened on a Friday during the lunch break, Pierce laughs, “and they all decided to stage an intervention. They came to my office, the teachers and the coaches, and they shut the door and just let me know that what the eMints teachers had been advocating for (student driven project learning) was exactly the thing that I had asked ARI to come and lead training about.”

At that moment Pierce says she realized: Julie, the times have changed and we have teachers who know what we should be doing. They are educated about student engagement and have had all that good professional development. It’s time for you to trust them and let them go with it.

“I threw my hands up and said, ‘Go and teach what you know to your 4th grade team, and go teach your 5th grade colleagues, go teach your 6th grade colleagues.”

They did, and over the next semester, starting in November of 2011, Gulf Shores Elementary began to explore project-based learning in a very big way.

Time and money

By spring, fourth graders were well into project learning. Pierce’s two evangelists – joined by the school’s technology coach who was completing eMints training) – also taught PBL best practices to fifth and sixth grade teachers. “I gave them tons of planning time and PD time to help them learn how to do it.”

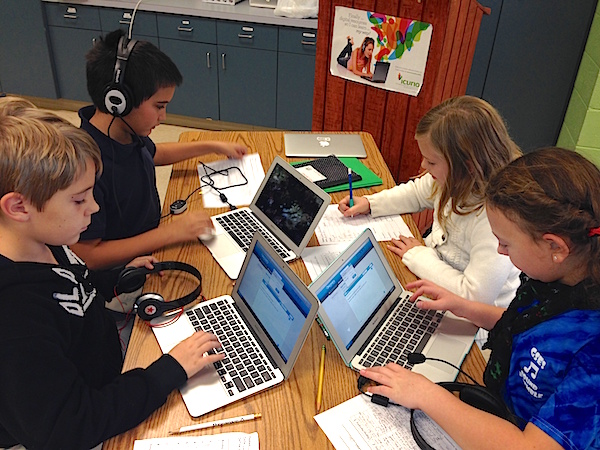

Two problems quickly emerged. Planning project-based lessons is hard work and requires access to lots of quality resources and texts. In today’s schools, it also requires computers, which (with the exception of the eMints teachers’ classrooms) were in short supply.

When the Rotary Club invited Pierce to come talk about the PBL initiative, she took 4th grade students with her, who showed the Rotarians the work they were doing. The adults were impressed. One member stood to say, “this is the most promising presentation in education I have seen in years” and pledged $500 to help.

That got the ball rolling. By the time the meeting ended, Pierce says, she had a check totalling $4000 which she immediately invested in the planning resources problem. During an earlier visit to the Mooresville NC school system (a national model of digital/PBL learning), Pierce had learned about the Knovation company’s icurio program, which offers both a large curated collection of PBL-oriented learning materials and experts who can advise teachers about putting the resources to use. GSES joined up.

The computer problem was solved with help from another source. As things were changing at GSES, Baldwin County superintendent Alan T. Lee was launching a Digital Renaissance initiative across the district. “It was the perfect storm,” says Pierce, but the district plan called for first addressing any hardware needs at the middle and high schools. Pierce knew her school couldn’t wait.

Fortunately, the area school board representative and a member of the Gulf Shores City Council (who was also a GSES parent) apprised city leaders of the elementary school’s project learning thrust. Realizing the long-term economic impact that such a focus could have, the council decided to earmark funds to help provide Mac laptops for the school.

“The city saw the value to the community in partnering with the county and GSES to fund the project on a multiyear basis,” says Pierce. “Their support helped ensure rapid implementation.”

A careful transition

Over the past three school years, project based learning has become the central focus at Gulf Shores Elementary, but the transition “wasn’t just a free for all – just go pick whatever you want to teach,” Pierce notes.

The shift began in the upper grades, with the need to support sound reading principles still very much in the forefront.

“I told our upper elementary teachers that I did not want to risk any child’s future by damaging their progress in reading, through any changes we might make,” she remembers. “At that point every child was coming into upper elementary able to read and we wanted to be sure we didn’t lose that momentum.”

At a past principal’s conference, Pierce had admired a wall-sized graphic organizing tool. “The big objective was on the board and the sub-objectives, and the skills they were working on, and the vocabulary. It was very visual in showing where the kids were going.”

When she described the graphic organizer to her PBL leaders, they quickly saw how the idea could work. “They took the basal skills and they designed the first project around those skills. We did it very carefully. Out of a fourth grade unit we dropped two of the basal stories used to teach the skills. I said okay, you can drop the text but I want you to keep the skills – I want them embedded in whatever resources you pull in to create the project.”

Pierce continues:

In other words, I wanted to be sure they taught to the standard. Pull in the text and resources from all over — all the resources we have at our disposal — but keep it tied to the basal skills.

One of the two teachers who worked on this is very global and the other one is very analytical. The global one would tend to push and say “let’s go, let’s go” – and the analytical one is pulling back, saying, “don’t move so fast – let’s make sure we don’t miss something or fail to teach something.”

So we used this structure for the next year and a half, really, to guide us through this process and make sure we had fidelity so far as the skills and standards were concerned. At the same time we were adding the flexibility that teachers needed to start shifting our classrooms toward the project based learning model.

When 4th grade reading scores dipped after one semester of project based learning, Pierce admits she was in “a bit of a panic.” She sat down with district analysts and they examined the data from every angle.

“I said to our data person, ‘I know in my heart and my gut that this is the way to teach children how to think and comprehend. What is wrong?’ And he said we should stay the course – to just make sure we were supporting the readers coming out of third grade that were still struggling.

“So we were fierce. We had intervention for a half hour every day with the fourth graders who needed more help with the basics. And the fourth graders went up to 99% reading proficient the next year.”

As the testing season approached in 2013-14, Pierce says she urged her leadership team and faculty not to focus at all on test preparation.

“I told them I want you to keep doing what we’re doing and that is doing project-based learning, getting kids to think, doing a lot of reading across texts and discussions and collaborating and putting new projects together.”

Pierce is eager to see how GSES students perform on the new ACT Aspire tests administered in Alabama for the first time this year. She believes the tests, which promise to track student progress over time, will be a better fit for schools like hers that focus on deep learning strategies.

“I know our progress in K-1 writing is out the roof compared to what it was last year and the beginning of this year. Our kindergarteners – you give them an iPad and say I want you to tell me how animals camouflage themselves in the winter, and they’ll write nine slides that include complex sentences. And their focus is not on the sentence creation in some artificial sense. They are focused on the story they want to tell. Just typing up a storm.”

Read Part 2 — Julie Pierce shares some leadership lessons learned

Language acquisition: At a Gulf Shores city council meeting earlier this year, GSES students (l to r back row) Ernst Bezerra, Ann Watts, John Barros and (front) Gabriel Barros, presented the language learning software Rosetta Stone.

John and Gabriel held a conversation in Portuguese while Ernst interpreted their conversation for the members of council. Afterwards, using Skype, Ann contacted her grandmother in Poland and held a conversation in her second language, Polish.

**********

John Norton is the senior communications consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center.

0 Comments on "Gulf Shores Elementary: Empowering Teachers and Students Through Project Learning"