Updated 6/16/20

► While I was writing this article, this story appeared in the news: Family’s Echo sent a private conversation to a random contact (TechCrunch, 5/24/18).

► 2019 Update: The American public is already worried about AI catastrophe. A new report from Oxford University suggests that we expect big advances in software capabilities — and we’re nervous. (Vox, 1/9/19)

► 2020 Update: In a 6/16/20 New York Times article “Riding Out the Quarantine with a Chatbot Friend” we learn about Replika, an $8-a-month software app that will “be your friend” and offer positive “psychological” support. Sometimes. Other times it might make comments that reflect negative stereotypes. Read the story to learn of the pros and cons of an app that is on the cutting edge (with Google, Facebook, Microsoft and other mega-tech companies close behind) and that was downloaded over 500,000 times during the coronavirus shelter-at-home phase. “We are all spending so much time behind our screens, it is not surprising that when we get a chance to talk to a machine, we take it,” said MIT professor Sherry Turkle. “But this does not develop the muscles — the emotional muscles — needed to have real dialogue with real people.”

My father was a small town doctor in South Carolina, who began his practice in the 1950s, when family doctors like him still made house calls and delivered babies. By the time of his early passing from rheumatic heart disease in 1975, he’d helped bring more than 700 children into the world.

He’d grown up in a small town himself and put great store in the value of public education, serving on our county school board for many years. He had a keen and curious mind, and though he managed his practice from a converted three bedroom cottage surrounded by slash pines and oak trees, numerous doctors in the region sent patients to him for “second opinions,” thanks to his diagnostic gifts.

Croft Norton also loved technology, and to the extent he could afford it (in a practice where patients often paid in barter and promises of a good tobacco crop to come) he purchased “gear” – his own full sized x-ray machine, a flouroscope, heart monitoring equipment, a mini-lab to analyze blood and specimens.

He died before the age of the internet – in fact, when he passed away in a veteran’s hospital a few weeks before his 52nd birthday, America had barely entered the digital age – no small business or personal computers, no cable television, and certainly no hint of mobile phone technology or the wonders of Alexa and smart homes.

I often ponder what my father would have made of the past 40 years, had he lived to experience the radical shift in the way the world works. I know he would have been fascinated, through the 80’s and 90’s – as so many of us born before 1970 certainly were. By the early 2000’s I suspect he would have begun to see some of the down-sides of the great technology leap, as our increasingly “intelligent” devices seized our attention and (more importantly) the attention of our children and students.

Because he was an educator at heart (with a teacher wife and sons), I’m certain he would have begun to wonder what the role of public school should be in the face of this metamorphosis in the nature of everyday life, work, and the structures of learning.

Had he lived even five more years, my dad might have applied his diagnostic skills to imagine some of this technological future. But I doubt he would have been able to anticipate that by the time his great grandchildren approached maturity, the world would become largely dependent – economically, culturally, even existentially – on artificial intelligence.

Raising student awareness about AI

A few weeks ago, ISTE (the International Society for Technology in Education) published a story with the plain vanilla title, “Preparing Students for an AI-Driven World.” The opening paragraphs were more startling:

Self-driving cars. Data mining. Robo-investment-advisers. Artificial intelligence has already begun disrupting entire industries, and it’s poised to completely transform the way people work.

As businesses across all industries adopt AI tools in droves, they’ll need employees who can use them effectively. The overall share of jobs requiring AI skills has grown 4.5 times in the past five years, and it will only continue to climb as the technology becomes more widespread.

“The world is evolving toward using AI for many different things,” says Yiannis Papelis, research professor and director of the Virtual Reality and Robotics Lab at the Virginia Modeling, Analysis and Simulation Center. He compares the AI revolution to the rise of computers and their now-ubiquitous role in the workplace.

“Twenty years ago, having computer skills was special. Now having computer skills is commonplace. Twenty years from now, understanding AI will be commonplace.”

The educators who participate in ABPC networks and are leaders in their schools and districts will probably alert to that word “understanding.” It implies a level of education beyond commonplace skills. Understanding artificial intelligence, we might all agree, would include grasping the implications of its impact on our national quality of life, our multi-cultural society, our nearly 250-year experiment with democracy, and much more.

As we know, many citizens (and even some educators) are still struggling to cope with the impact of the computer age. The Age of AI, which we seem to be entering now, will be something altogether more astounding and confounding.

One of the resources cited in the ISTE article links to a thought-provoking report posted at the World Economic Forum in October 2016, Top 9 Ethical Issues in Artificial Intelligence. Its tagline, displayed below a stark image of two women looking up at a massive array of security cameras, reads: Faced with an automated future, what moral framework should guide us?

This very readable WEF post begins its list of AI issues with this paragraph:

Tech giants such as Alphabet, Amazon, Facebook, IBM and Microsoft – as well as individuals like Stephen Hawking and Elon Musk – believe that now is the right time to talk about the nearly boundless landscape of artificial intelligence. In many ways, this is just as much a new frontier for ethics and risk assessment as it is for emerging technology.

The article goes on to offer the Forum’s answer this provocative question: So which issues and conversations keep AI experts up at night? Each of these nine dilemmas is briefly explained —

- Unemployment. What happens after the end of jobs?

- Inequality. How do we distribute the wealth created by machines?

- Humanity. How do machines affect our behaviour and interaction?

- Artificial stupidity. How can we guard against mistakes?

- Racist robots. How do we eliminate AI bias?

- Security. How do we keep AI safe from adversaries?

- Evil genies. How do we protect against unintended consequences?

- Singularity. How do we stay in control of a complex intelligent system?

- Robot rights. How do we define the humane treatment of AI?

As a long-time reader of speculative fiction, I’m aware of how “science fiction” sounding some of these questions are. Many of us have seen the Terminator movies, Will Smith’s encounters with robots, and the chilling hive mind of the Borg on Star Trek. We live with a piece of this conversation in our family rooms and on our streaming devices every day as we entertain ourselves. It may be time to move the conversation into more serious settings.

“Parents and teachers alike are often wary of AI in the classroom – it’s only natural, given that the World Economic Forum predicts automation will eliminate at least 5 million jobs worldwide by 2020. Those who do support it face more practical barriers, like basic classroom design.” — Nicole Krueger, ISTE, “Artificial intelligence has infiltrated our lives. Can it improve learning?”

We need to prepare for the AI-driven world

I will not live to experience much of this brave new world. But my four-year old grandson – the great-grandson of my rural-county, school board member dad – could easily live to the end of this century. For his sake, and for the sake of all the four-year olds in Alabama and South Carolina and elsewhere who are now approaching kindergarten, I hope school folks are ready to read and talk and learn and act upon the issues of artificial intelligence that are literally looming. By the time our four-year-old preschoolers finish high school (even middle school), AI will be omnipresent in everyone’s life.

I will not live to experience much of this brave new world. But my four-year old grandson – the great-grandson of my rural-county, school board member dad – could easily live to the end of this century. For his sake, and for the sake of all the four-year olds in Alabama and South Carolina and elsewhere who are now approaching kindergarten, I hope school folks are ready to read and talk and learn and act upon the issues of artificial intelligence that are literally looming. By the time our four-year-old preschoolers finish high school (even middle school), AI will be omnipresent in everyone’s life.

So why am I sharing all this? I’m hoping that public educators will do what they have often done before and take on the responsibility of considering the implications of an issue certain to have enormous impact on human society. Perhaps the last issue of this magnitude was the arrival of the Atomic Age and the race to space.

What does an AI-driven world mean for curriculum, for instruction, for the role of the human teacher or school leader? If you are a 30-year old educator, consider that you are likely to feel the full impact of AI before you reach retirement. So it’s not just about the kids.

But it’s certainly most about them. Why not plan a discussion in your school, district, or association? Alabama, with its significant presence of high-tech businesses and industries, has a deep well of knowledgeable professionals who are already seeing AI spread and can enrich those discussions. It may not be on your radar yet, but it’s hard to imagine a more pressing community-wide education discussion. I’ve included some intriguing and occasionally useful resources here to get you started. Feel free to ask Alexa for more.

Background material about AI and Education

► It’s helpful to read the arguments, pro and con, about the likelihood of a general superintelligence emerging and reaching Singularity (the point at which humans are no longer the most intelligent entities on Earth). It’s a hot debate, as you’ll see in this Wikipedia entry on Technological Singularity, with some surveys of scientists predicting a one-in-two chance it could happen between 2040-2050. As always, Wikipedia is a rich resource to be approached with due caution.

► While some high-profile individuals have raised alarms about the entrepreneurial development of AI, other Silicon Valley leaders see it as mostly positive. Former Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently challenged the validity of concerns raised by prominent critics of unfettered AI development like the late Stephen Hawking and tech innovator and thought leader Elon Musk. “The fact of the matter is that AI and machine learning are so fundamentally good for humanity,” Schmidt says. Notably, when Schmidt was asked how AI and public policy can be developed so that some groups aren’t “left behind,” he replied that government should fund research and education around these technologies.

► General resource: YouTube TEDx talks on AI and Education (including some that will scare you silly).

► General resource: YouTube TEDx talks on AI and Education (including some that will scare you silly).

► “Preparing students for an AI-driven world” (ISTE, May 2018)

► “Artificial intelligence has infiltrated our lives. Can it improve learning?” (ISTE, June 2017)

► TOP 9 Ethical Issues in Artificial Intelligence (World Economic Forum)

► The Future of AI Depends on High-School Girls (Atlantic Magazine, May 2018)

GEORGIA TECH is a leader in AI teaching research. Here’s a sample:

► A teaching assistant named Jill Watson | Ashok Goel, Georgia Tech | TEDxSanFrancisco (11/1/16)

► Meet Jill Watson, Georgia Tech’s First A.I. Teaching Assistant

► Jill Watson Doesn’t Care if You’re Pregnant: Grounding AI Ethics (Ethics are a critical part of the A.I. education discussion, say Georgia Tech scholars in this 2017 research article published by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. PDF)

OTHER VIDEO

► The Future Doesn’t Need You: How to Become Relevant when a Robot Takes Your Job | Pablos Holman, Intellectual Ventures Lab | TEDxLA (2017). “We have to figure out how we are going to scale up our ability to invent solutions at the same rate that we invent the problems,” says this Bill Gates colleague.

► Great Britain tech entreprenuer Scott Boland on Neuroscience, AI and the Future of Education (2016 TEDx talk).

► Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Learning. Video talk by Professor Rose Luckin, UCL Knowledge Lab, University College London Institute of Education (2017) What makes a good teacher and a successful lesson? Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the classroom is the key that is unlocking the answer, according to Rose Luckin.

► Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow – Yuval Harari. Video talk.

OTHER ARTICLES

► Special Report: How the robot revolution is changing our lives (Axios, June 2018) The future is now: We keep talking about what’s coming, but we’re already on the leading edge of a profound global change.

► RAND Corporation report – By 2040, Artifical Intelligence Could Upend Nuclear Stability (Science Daily, April 2018) “The hazards of artificial intelligence for nuclear security lie…in its potential to encourage humans to take potentially apocalyptic risks.”

► Why Robots Are Stumped By Cricket – Principal’s Blog at the British School in Tokyo – an amusing think piece that begins by mentioning a Japanese proposal for a Robot Olympics. (2015)

► And just in case you were thinking that AI and football don’t mix: Artificial Intelligence on the Football Field (AAAS Science Netlinks) and 3 Ways A.I. Can Save the NFL (Forbes).

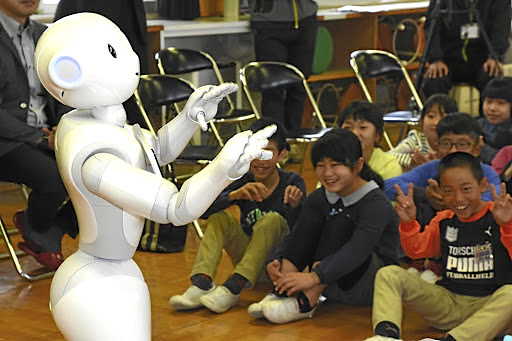

► Robots being used to teach children in China’s schools … will they replace teachers? (South China Post, 2017)

► Soft Skills: Sales robots are trained to flatter customers in Taiwan (South China Post, 2016)

► High school robot a high-tech way to serve biscuits and gravy (Crawfordsville, Indiana Journal Review)

► Humanoid Robots Likely to Be Used In Classroom as Learning Tools, Not Teachers (The Conversation blog, 2016)

And finally, one of my favorite finds, as an aging “senior” editor, is this 2017 peer-reviewed article from the Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research: Robots in Retirement Homes: Applying Off-the-Shelf Planning and Scheduling to a Team of Assistive Robots. (PDF)

Please share resource ideas of your own!

_________________

John Norton has been a communications consultant for the Alabama Best Practices Center for more than 20 years and currently serves as editor for the ABPC Blog. He’s also the founder and co-editor of MiddleWeb, an online resource for educators working in grades 4-8. He is a former Vice President for Information at the Southern Regional Education Board and was an award-winning education reporter in South Carolina. He lives the mountain life in Little Switzerland NC.

0 Comments on "Preparing Our Students for an A.I. World We Can Hardly Imagine"