Learned helplessness is a topic that resonates with many teacher and school leaders today. Check the past year’s content at your favorite education websites and publications and you’ll see what I mean.

Learned helplessness is a topic that resonates with many teacher and school leaders today. Check the past year’s content at your favorite education websites and publications and you’ll see what I mean.

When ASCD’s monthly Education Update arrived last winter, with the cover article titled, “The Ins and Outs of Academic Help Seeking,” I put it on top of my list to read.

The article by Sarah McKibben (member access here) began with an important observation from Robyn Jackson, author of many books including Never Work Harder Than Your Students —

You notice a student stumbling through a problem or concept and your first impulse is to “rescue” him. Maybe it’s because he’s frustrated and on the verge of giving up, says ASCD author Robyn Jackson. But “we also rescue kids because it’s the most expedient way to move on to the next kid. Especially when several students are asking for help.”

In a classroom that emphasizes productive struggle, “the biggest thing teachers can do is resist the urge to rescue students,” says Jackson. “When teachers help too much, they reinforce the idea that it’s about getting it right and not about the struggle of learning.” Eventually, students won’t put forth the effort at all because it’s “not being rewarded or emphasized.”

So, when we act on the temptation to rescue that student are we really doing him or her a favor? Robyn Jackson doesn’t think so and her views are shared by many other education experts. All of us can benefit from what is called “productive struggle,” by persisting through a problem or challenge without giving up.

So how do we do this in real classrooms?

Productive struggling is often easier said than done. Helping students develop strategies for persisting through a difficult challenge is key to their success. And, part of the strategy is helping students learn how to ask for help in productive ways.

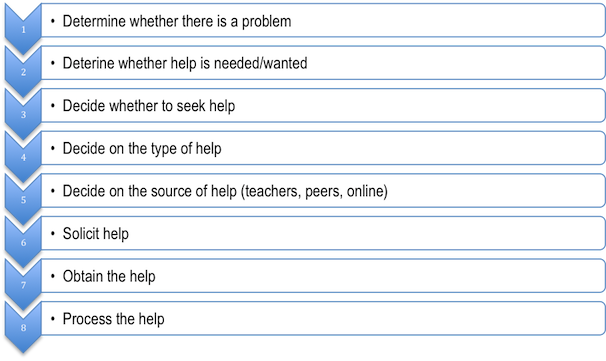

Stuart Karabenick, a research professor at the University of Michigan, developed a “Help-Seeking Framework” to support and guide teachers and students when faced with struggles. The stages of this framework aren’t always used in this order, but Karabenick suggests that each stage is important to mastering productive help-seeking.

According to the Education Update article, teachers should not discount the fact that, for students, the struggle is real. It is important to acknowledge the struggle and then help the student determine whether the struggle is “productive” or “destructive.”

According to the Education Update article, teachers should not discount the fact that, for students, the struggle is real. It is important to acknowledge the struggle and then help the student determine whether the struggle is “productive” or “destructive.”

If the struggle is productive, students should try to continue to work on their own to reach a solution and/or become “unstuck.” But, if it turns destructive, students should seek help, guided by the framework above.

When and how should teachers help?

Determining whether or not to assist students is a learned skill and takes practice, by both teachers and students. Carol Dweck, the foremost expert on the growth mindset, suggests that terminology matters. Suggesting that students ask for “input” rather than help, might help normalize a pattern of productive help-seeking.

In her MiddleWeb article “17 Ideas to Help Combat Learned Helplessness,” former school leader Sarah Tantillo, now an author and literacy consultant, uses an If / Then / Do This Instead format to guide teachers through a variety of typical teacher and student behaviors that unintentionally promote learned helplessness. She then suggests alternatives. Here’s an example:

► Stop sweeping in to save the day

IF: You answer student questions immediately during independent work time…

THEN: Students learn not to try or struggle on their own. They’ll always wait for you to swoop in!

SO DO THIS INSTEAD: Set a timer as soon as 100% of students are actually working and you have announced that you will address questions after 5 minutes of sustained work time. When the timer goes off, you can say, “Raise your hand if you need my attention,” and write student names on the board. Students then return to work and you address questions in the order of the names on the board so students aren’t sitting there waiting with their hands up (avoiding productive struggle).

Tantillo concludes with a powerful thought that recalls the work of our own Jackie Walsh and Quality Questioning:

“IF you ask all the questions, THEN students never learn to ask their own or invest themselves enough to wonder. SO, create time for asking and answering questions about the text, problem, or content at hand. Invest students in seeking their own answers. Keep the wonder alive!”

We can overcome listless learning!

As you peruse all these insights into learned helplessness, think of your own students—or, if you are an administrator, of your own teachers. What are you discovering about overcoming listless learning and promoting productive struggle? What tips can you share with our readers?

0 Comments on "Turning Students’ Learned Helplessness into Productive Struggle"