When I walked into an elementary school classroom during an recent Instructional Rounds visit, a group of students were pushing and shoving each other. It was a teacher’s bad dream come true – a disruption breaks out just as visitors enter your heretofore reasonably well-ordered learning space.

When I walked into an elementary school classroom during an recent Instructional Rounds visit, a group of students were pushing and shoving each other. It was a teacher’s bad dream come true – a disruption breaks out just as visitors enter your heretofore reasonably well-ordered learning space.

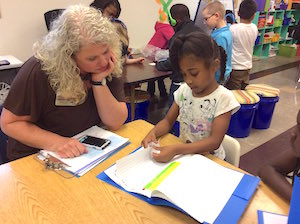

But this teacher adeptly handled the situation, then invited me to join any of the six groups of students in the room to discuss their data notebooks. I chose the group that included those three rowdy boys because I was afraid no one else would.

And, I’m glad I did. What happened next was another reminder of the importance of evidence-based observation (sometimes called “descriptive observation”), a basic tenet of the Instructional Rounds process.

For 10 minutes I spoke with the students about their learning. One student showed me a photo of the day he dressed up as B.B. King during Black History Month. I learned more about B.B. King’s life and art, even though he is one of my favorite musicians.

Another boy showed me his quarterly assessment scores on his chromebook, pointing to the growth he made, but noting that he was not yet satisfied. “I’m going to work even harder. I know I can do it!”

When I stood to leave, one of the rowdy boys looked up and said, “It was a true pleasure talking with you.” I couldn’t have agreed more!

In a school in another district, I heard about Space trash from a group of fifth graders. They were learning how to analyze nonfiction text. One student pointed out the danger of old satellites falling from orbit to our planet’s surface. Another speculated on steps that could be taken to both minimize Space trash and its threat.

In a different classroom the teacher was preparing for a novel study. Students were to choose among a group of books based on their current reading comprehension skills. The teacher showed students what was available on the website she had made for them and pointed to the summary of each novel.

One student asked, “Why are you giving us the summary? Isn’t that a spoiler?”

To which the teacher responded, “I’d consider it more of a teaser.”

Instructional Rounds are full of aha moments

Participants in the ABPC Instructional Rounds program always experience many informative and affirming interactions with kids – the kind that remind us not to jump to conclusions with too little evidence. It’s all about watching, listening and reflecting.

Professors from the Harvard Graduate School of Education, led by Richard Elmore, originally created Instructional Rounds to help school superintendents in the northeastern part of the U.S. develop a common vision of teaching and learning.

Since then, the concept of Instructional Rounds has morphed into many different versions across the United States (and the world!) – one of which the Alabama Best Practices Center has adapted for our use.

In addition to helping participating educators develop a common vision and language for effective teaching and learning, Instructional Rounds offer participants the opportunity to practice descriptive observation — that is, to describe what they actually see and hear in precise terms, instead of what they think about what they see. Observe, don’t opine.

As we prepare participants for Instructional Rounds and the use of descriptive observation, we compare the process to that used by a court reporter, or a detective who gathers facts rather than rushing to conclusions. (Those of my age will remember Joe Friday of Dragnet fame).

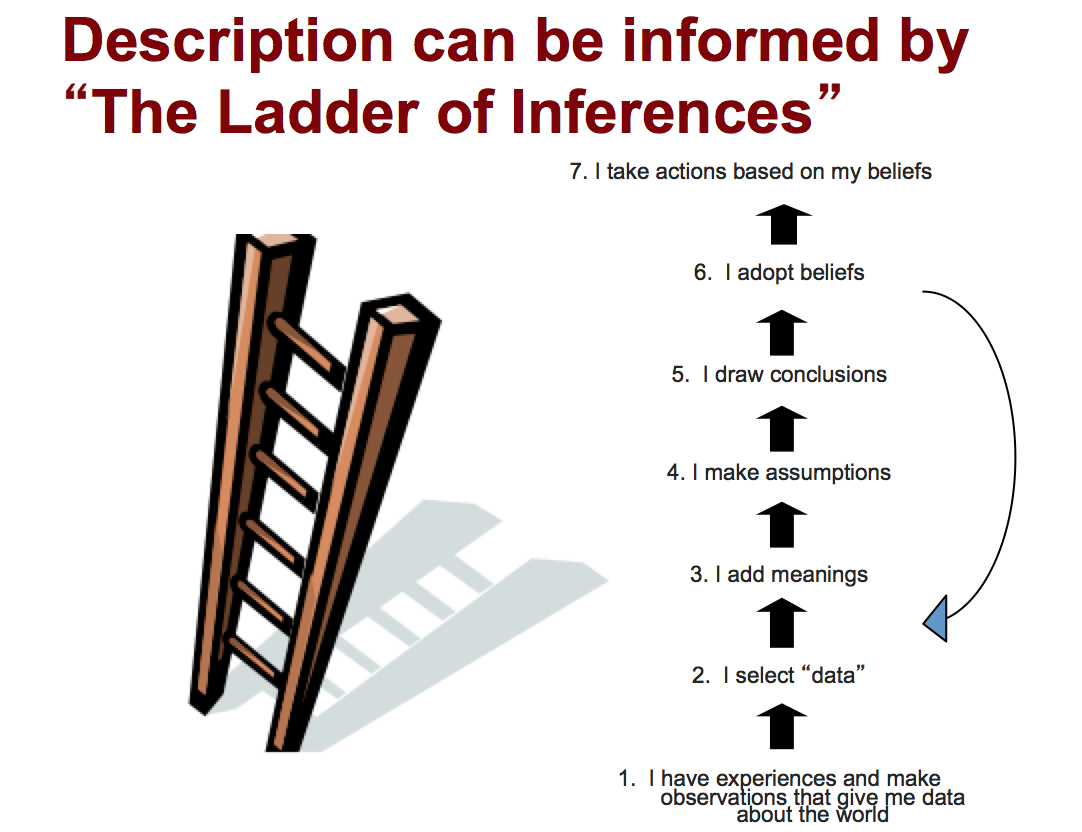

We also call upon the Ladder of Inferences, developed by Chris Argyris and popularized by Peter Senge in The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook.

In short, the Ladder of Inferences reminds us that as human beings take in data (for example, we see something), we quickly make judgments about what we are experiencing. We sometimes too quickly make inferences about what we see. And, that can lead us to making inaccurate assumptions.

Before taking action or making judgments, Argyris suggests that we look back at our original data to ensure that our inferences are on target.

For example, when we look outside to check the weather, we look up at the sky and based on our observations, we might conclude: “Oh, it’s a sunny day! I won’t need my umbrella.”

But if we were using descriptive observation, we might note something like: “The sky is a light blue color today and the sun is just above the horizon. There are 8 clouds within my view and they are white and full.”

While we may not need to be mindful of the Ladder of Inferences when we’re determining the weather (although better data-gathering might mean we put the umbrella in the car!), it is critically important to use when observing classrooms.

Look back at the story I told at the beginning of this blog. If I hadn’t sat down at the table with the three unruly students, I might have inferred that they were discipline problems and probably not learning anything.

Instead, by spending time with the three students and listening to them talk about their learning – in the role of descriptive observer – I had the opportunity to check my first impressions and make a more appropriate inference.

Observational, not judgmental

Driving home from three back-to-back Instructional Rounds, I wondered about what might happen if all of us committed to taking off our metaphorical “judgmental hat,” opting instead for the use of descriptive observation.

Imagine how teachers would respond if an observer simply reported that: “Not all students were engaged in learning.” Compare that to a more descriptive observation: “During the segment of the lesson that was whole group instruction, you asked 12 questions that were answered by nine of 24 students. One student answered three of those questions.” Which is more useful and likely to spark reflection?

When we visit a classroom during Instructional Rounds, we ask students what they are learning and then write write down their responses verbatim.

For example (see video clip below), a fourth grader told me she was learning how to measure area and perimeter so that she could develop a grid that captured the floor plan of her school in a scaled size. Her fourth grade colleague noted that he was learning how to code a robot so the robot could navigate and describe each of the rooms in the scaled version of their school.

Think about how much more robust these facts are than simply noting that students could “describe their learning target.” And consider what these kinds of questions and answers tell you about the level of learning of those you talk to.

Read about how one Alabama district — Enterprise City — is using

Instructional Rounds as part of their school improvement efforts.

No doubt many readers are wondering what happens to the information we gather during our observations in the classrooms of schools we visit. You can learn more about that process by browsing this PowerPoint (start at slide 29). This example was used to prepare observers for their visit to Oxford Middle School last month, and it’s typical of our Instructional Round PPTs.

I hope this will be the first of several blogs I write about the Instructional Rounds I’ve been privileged to facilitate. And I hope some of you who have participated will do the same.

You can start by sharing a comment here! What are you learning from your participation in Instructional Rounds?

0 Comments on "Instructional Rounds Help Us Learn Not to Jump to Conclusions"