Let’s apply the chicken-or-egg question to school improvement. Which should come first – identifying the problem or implementing a solution?

Let’s apply the chicken-or-egg question to school improvement. Which should come first – identifying the problem or implementing a solution?

The answer may seem obvious – but is identifying the problem always our first response? Not just recognizing that “we have a problem” (that’s a healthy first step) but really digging in and understanding the most likely source(s) of the issue at hand (e.g., lagging student achievement).

As I listened to some dialogue at a recent gathering of school leaders, I had an ah-ha moment: “They’re moving immediately to solution-seeking, rather than problem-finding,” I thought.

Educators, by nature, are problem-solvers. They want things to work, they want students to succeed, and they want to make the world a better place. But they often feel pressed by time in their efforts to achieve all these worthy goals.

So, naturally, they look for answers. But, sometimes, do these searches turn more toward solution-seeking and less toward understanding the problem? And does that tendency lead us to treat the “symptoms” without being certain of the cause?

Or put another way: until you really analyze and define a problem, does it make sense to invest your organization’s time and energy on a solution?

Searching for answers

Driving home after that meeting, I pondered these questions and began to wonder how we can encourage educators to first ask “why” — What is the problem and why is it happening? — before jumping to “how?”

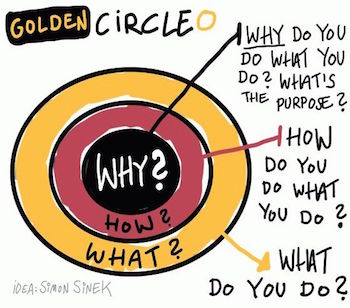

Remembering Simon Sinek (see his Ted Talk here) and his “Golden Circle” rule, where he suggests that one always begin with WHY?, I ordered his book, Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. There were some good ideas there, but his focus was primarily on identifying and explaining your mission or goals in life. It was not focused on the type of problem-solving I was seeking.

Remembering Simon Sinek (see his Ted Talk here) and his “Golden Circle” rule, where he suggests that one always begin with WHY?, I ordered his book, Start With Why: How Great Leaders Inspire Everyone to Take Action. There were some good ideas there, but his focus was primarily on identifying and explaining your mission or goals in life. It was not focused on the type of problem-solving I was seeking.

Next, I turned to Peter Block’s The Answer to How is Yes: Acting On What Matters. And I found some nuggets:

If we could agree that for six months, we would not ask ‘how?,’ something in our lives, our institutions, and our culture might shift for the better. It would force us to engage in conversations about why we do what we do, as individuals and as institutions. It would create the space for longer discussions about purpose, about what is worth doing. It would refocus our attention on deciding what is the right question, rather than what is the right answer (p. 3, emphasis added).

Later in the book, Block stresses the importance of slowing down and taking time to understand the problem, process, or situation: “Thinking, reflection, and going deeper take time and require us to get personal—to question our own beliefs, theories, and feelings. When we decide to set aside time to think, to reflect, we get nervous. The fear is that if we took the time for questioning, for thought, for introspection, we might not have what it takes to act or do” (pp. 75-6).

This is solid advice for all of us. We don’t take enough time to reflect or to take the “balcony view.” As a result we often don’t really understand what’s going on and what we should do next. But, in spite of these words of wisdom, Block’s book, like Sinek’s, was more about finding purpose in one’s life and actions.

Insights from a parable

Still looking for resources about problem identification and understanding, I turned to my colleague Thomas Rains, who is the VP of Operations and Policy at A+ Education Partnership. Thomas asked if I had ever read The Goal by Eliyahu Goldratt. “It’s a novel that I had to read in graduate school…I wonder whether it would be helpful to you?”

A novel read in public policy school? Well, I was intrigued and picked up the book. (See here for a summary of the book).

A novel read in public policy school? Well, I was intrigued and picked up the book. (See here for a summary of the book).

In short, the novel is a parable about a plant that is threatened with closure because of backlogs in meeting orders, and the inability to turn a profit. The plant manager is confronted with a three-month deadline to “fix it” or be shutdown.

By chance, at an airport, he encounters his former physics professor, who is now a sought-after business consultant. This professor, over time, leads the plant manager and his business colleagues to look at the “why” and begin to identify the problem before seeking the solution.

Over time, with lots of experimenting, the plant manager and his leadership team come to understand the importance of slowing down and asking questions like:

► What to change? (and I would add “Why?”)

► What to change to?

► How to cause the change?

What struck me most about this novel was the realization that in most cases, when faced with a problem, people turn to data and look for solutions within their current framework or paradigm without either deeply understanding the problem or questioning their current process.

I was also reminded that people need to co-own their problems and discover the right next steps together. The consultant in the book asked questions, but didn’t give answers. He knew that if he “solved” the problem for the leadership team, chances were that his solution would fail due to lack of ownership and deep understanding.

What do we understand?

As educators, we know that our number one goal is to improve student learning. That’s a given. But, how to get there can be both challenging and, in at least some ways, different for each school or district.

We want to improve student engagement. We want to pursue blended learning. We want to increase rigor in the classroom. Okay. But, before taking action, what might happen if we spent time first asking why we have identified a problem and why is it currently a challenge worth addressing.

For example, when thinking about student engagement, why is it important? In what ways can it be a vehicle for improving student learning? What does true student engagement look like? In what ways can we ensure that state standards are guiding student learning – and not the textbook? And, in what ways can we ensure that students see the context for what they are learning AND why that is important?

For example, when thinking about student engagement, why is it important? In what ways can it be a vehicle for improving student learning? What does true student engagement look like? In what ways can we ensure that state standards are guiding student learning – and not the textbook? And, in what ways can we ensure that students see the context for what they are learning AND why that is important?

Ultimately, questions like this might lead us to ask: What could we do to improve if we didn’t accept our current processes as non-negotiables?

Asking, reflecting, and dialoguing with each other — these are the steps that will help us break our addiction to quick fixes and shift our perspective from solution seeking to problem solving.

As you think about your school or district, what are you learning about problem solving? How are you using “why questions” to ensure you really understand the problem and are ready to pursue effective change ideas?

0 Comments on "Problem Solving Shouldn’t Begin with Solution-Seeking"